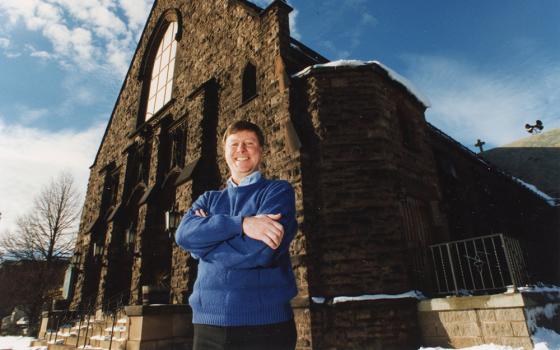

Fr. James Callan, then pastor of Corpus Christi Parish in Rochester, N.Y., poses in front of the church in 1997. (NCR file photo)

(NCR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

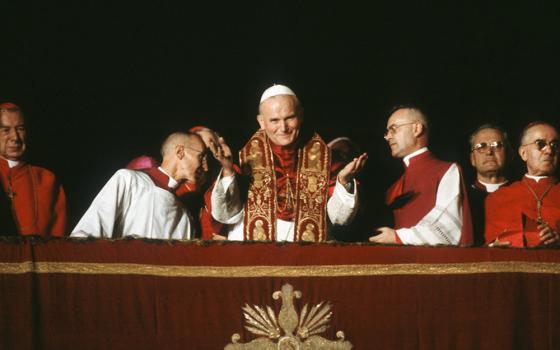

In 1997, as the church grappled with the stirrings of reform and the limits of tradition, the National Catholic Reporter captured one of its most provocative moments. Editor Tom Roberts dispatched reporter Arthur Jones to a parish in Rochester, New York — a community already abuzz with whispers of change.

What Jones uncovered at Corpus Christi Parish was the groundbreaking ministry of Fr. James Callan, a priest whose daring vision and unorthodox approach would soon shake the very foundations of ecclesiastical authority.

At the heart of that NCR report was a striking, full-page, tabloid-style black-and-white photograph of Mary Ramerman in an alb, presiding at the altar. It was a vivid symbol of a liturgical shift that challenged the old guard.

The dramatic photo perfectly captured Callan's ministry, which was marked by his support for women's ordination, his blessing of same-sex unions, and his radical practice of offering Communion to non-Catholics, earned him a reputation as a renegade.

Under his pastoral leadership, Corpus Christi had been transformed from a dwindling parish into a vibrant, multiracial community of nearly 3,000 souls, pioneering initiatives from destigmatizing AIDS to providing shelter and support for the disenfranchised.

In 1999, these very acts set him on a path that would forever redefine what it means to serve and transform a community.

After the NCR story and photograph were published, the bishop at the time, Matthew Clark, transferred Callan out of the parish. He told Ramerman she was forbidden from preaching or being on the altar if she wanted to remain on staff. She resigned. The diocese then fired six people who were in charge of ministries.

Subsequently, a large number of people met to discuss their future and ultimately decided to split away from the institutional church and begin their own congregation, Spiritus Christi.

Callan and a second priest who had been at Corpus Christi decided to join the new community. Ramerman was the founding pastor and Callan was listed as an associate. The diocese notified the priests and anyone else who had left the original parish for the new community that they were considered excommunicated.

Spiritus Christi remains a vital community today.

Last December, we said goodbye to Callan at the age of 77. His death in Rochester — after a life marked by unyielding commitment to social justice and an inclusive vision of the church — reminds us of the enduring power of courage and conviction.

As we celebrate the National Catholic Reporter's 60th anniversary, we republish Jones' landmark report. It stands as a testament to fearless journalism and to a ministry that dared to imagine a church without boundaries — a church where, in Callan's own words, "there are no disposables in the family of God."

Join us in revisiting this unforgettable chapter in our history — a tribute not only to bold reporting but also to a visionary priest whose legacy of unconditional love and radical inclusion continues to inspire.

Amid urban misery, a life-changing haven

Feb. 28, 1997

By ARTHUR JONES

NCR Staff

ROCHESTER, N.Y. — No way was Mary Anne Ramerman going to live in this dump. For one thing, she and her husband, Jim, were from California and here it was May and still snowing. Slush everywhere.

The parish welcoming committee had taken the couple to the house they'd live in.

Live in, that is, if, after a get-acquainted week with Corpus Christi parish people, they decided to join the parish ministry staff.

The house had been donated to the parish and furnished with leftovers. It was falling apart and on a street notable only for its squalor and the number of derelicts.

The Ramermans were polite to the parish staff, but when the couple stepped inside and she closed the door behind them, she looked at Jim and said, "You've got to be kidding. No way in the world. If you think I'm coming to this, you're crazy."

There was worse ahead. After the interview — 40 members of Corpus Christi parish peppering them with all sorts of questions, from the personal to the theological — the talk turned to salary.

The priest, Fr. James Callan, told them to pick their own figure, just ask for what salary they needed to support themselves and their 2-year-old, Matthew.

"I thought you couldn't afford anything," countered Ramerman. She'd heard that the parish payroll was an envelope with a little money in it and that people went to the envelope sparingly when they needed some.

"Oh, we can't really," Callan replied. "Actually we don't have any money right now, but that's why you can ask for whatever you want. We'll just start from there."

Jim and Mary Anne Ramerman had had better offers. In California where they worked in the Santa Rosa diocese youth ministry, Stockton Bishop Roger Mahony had offered them a job. In Seattle, Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen was beckoning with an exciting challenge. But a Rochester-born friend living in California told the Ramermans they ought to check out Corpus Christi parish in this upstate New York city. So, Jim Ramerman had traveled out and gone on a parish retreat with Callan and "Sister Marjie" (Sr. Marjory Henninger), twin pillars of the parish's rebirth.

He'd returned and urged Mary Anne to take a look for a week. They left Matthew with her parents.

Impressed by the caring

One day during the Rochester visit, they walked out of "the total dump," as Mary Anne Ramerman called it, and over to the Corpus Christi health center for a prayer service. During the service a man came in off the street sobbing because his daughter had just died of sickle cell anemia.

He was a neighborhood man. The small community gathered around him and held him, talked to him and listened. The Ramermans were impressed by the caring. They'd already been to Dimitri House, the parish home for the homeless, and to Rogers House for ex-offenders adjusting to life outside prison. They had looked in on child care in the former parish school on Main Street.

Next day, the Ramermans went with parish people to Attica State Prison at 5 a.m. Ramerman had been told not to bring her purse because visitors were not allowed to take anything inside.

When they arrived at Attica, she had no identification. The little group wondered what to do. The leader put his hands on her head, prayed and said, "We'll go in." And at each security check, with Mary Anne bringing up the rear, the guards — after looking at everyone else's identification — waved her through.

Fifteen years later, all of those years spent in Rochester, Mary Anne Ramerman, fresh from preaching and distributing Communion at the Monday noon Communion service, can laugh at the memory. "Hey," she said, with a shake of her auburn hair, "you can't explain it. That week was a life-changing experience."

Mary Ramerman is seen on the cover of the Feb. 28, 1997, issue of National Catholic Reporter, for an article about Corpus Christi Parish in Rochester, N.Y. (NCR photo/Teresa Malcolm)

Corpus Christi is a life-changing parish. Dip into parish life at any point and the story is the same:

A decade ago, when Corpus Christi was trying to buy two buildings for what became Demetria House, a drop-in center for the hungry and homeless and a residence for men in recovery, a couple getting married donated their wedding money.

A couple of weeks ago at 5 p.m., just as the parish health center was closing, a 14-year-old girl came to the door with her bag. Her mother had beaten her again. The girl had walked out of the house with nowhere to go. Center director Eileen Hurley and her fiancé, Patrick Trevor, canceled plans for the evening so they could get the girl into a safe haven.

"My gosh," said Pat and Maureen Domaratz, looking around the parish in 1991, "you've got Matthew 25 covered almost. Prisoners. Homeless. But one thing's missing — clothing." They started Matthew's Closet. Clothing is piled to the ceiling in the former classrooms of the old school building they share with the day care center.

Jim Callan never had any doubts it would be like this. His seminary rector, Fr. Joseph Brennan, advised by Callan that the seminary was terrible and new courses were needed, called him "a romantic, arrogant, utopian son-of-a-get-outta-here." Callan said he would put it on his gravestone. When seminarian Callan was called by the bishop to be told he would be refused ordination, it didn't help that Callan turned up wearing a tie.

The bishop later relented, preached at Callan's ordination Mass and urged him not to forsake his ideals.

He hasn't. His activism extends beyond parish boundaries. In the late 1980s, he staged a series of protests with Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan and others at the Seneca (N.Y.) Army Depot, where nuclear material was stored. After a 1989 arrest at the depot and release on their own recognizance, Callan and Berrigan went to a Geneva, N.Y., abortion clinic and sat in at the office of the clinic president.

When the priest took over Corpus Christi 21 years ago, Callan was 28 and a handful for any bishop. Corpus Christi parish was a handful for any priest. It was about to be closed.

Once a 'plum'

Founded in 1888 — the area was suburbs then -- this was the plum Rochester assignment after the cathedral. The vicar general always lived here. By the 1950s, the booming parish had 5,000 parishioners and eight Sunday Masses. In the 1970s, after Rochester's riots and white flight, 200 parishioners remained, spread very thinly across four Sunday Masses.

There was practically no money coming in, yet Callan canceled the only income producer, bingo, and asked the parishioners to tithe. In winter, the church and school cost $10,000 a month to heat. He vowed the parish would always meet its diocesan financial obligations, and then liquidated its $7,000 in stocks and bonds, viewing that type of investment as unworthy.

"We got rid of bingo and started giving money away," said Callan. "Money came in. Just miraculously, which is the expectation."

Callan decided not to disturb the Sunday folks' liturgy too soon.

Instead, he asked around to see if people would like a different kind of liturgy on a Thursday night, "the night of the Lord's Supper" (the feast of Corpus Christi traditionally was the Thursday after Trinity Sunday).

A few came, sat on the carpet in the sanctuary around the altar, played guitars, shared the homily and the eucharistic feast. Then they all went out for coffee. Within a couple of weeks there was a core group of about 30 people.

Callan had an image of what he wanted. He was one of eight children of Philip and Lucile Callan in a house on Winona Boulevard where each dinnertime saw 12 people (two grandparents also lived in the house) gathered at the table. Those mealtimes involved debating items of importance ripped from the daily newspaper and forays into the encyclopedia to ascertain facts. And the rosary. On their knees immediately after dinner, without exception, seven nights a week. The domestic church.

Callan's experiment at Corpus Christi worked.

"Thursday nights we generated a church within a church, basically," said Callan. "Close, a real sense of community. Young people started to join us. Single people came, met, fell in love. In time, married. Had babies. There weren't any babies in church — never heard one cry — till then."

The Thursday-nighters said, "We can't just be a club." The answer was outreach. They operated as a unit. When a refugee family flew in to be settled, all 30 people were at the airport to meet them.

Morning walks

That was by night. By day in 1976, Callan and the staff, which was Sr. Marjory Henninger, looked at each other and came to an agreement. Each morning, Callan would walk one way on Main, she would walk the other and they'd knock on doors, introduce themselves to people on the street and invite them to come to church. Then they'd meet for lunch and ask each other, "How'd you do?"

Callan would say he'd heard confession in a kitchen; Marjie would recount a conversation on the street.

Henninger wanted to open a neighborhood drop-in center. They rented an old barbershop for $75 a month. Cookies and coffee to whoever came in, neighborhood people. Kids got help with homework.

"I'd help them with their homework. Follow them home, meet their parents, stuff like that," said Henninger. "Being a 'present moment' person, I'm the kind of person that does things first and puts a name and organization to it later."

In time, the drop-in center was incorporated into more of the three-storefront building that today is the health center.

Callan has a serious weakness. His temptation is abandoned buildings. If he weren't a priest, he'd probably be a property developer.

The barbershop's owner offered Callan the riot-gutted block for $16,000. Callan said no, $8,000. "Come back when you want to give it away," Callan said. A week later Callan got it for nothing. When the parish had to buy the building that is Demetria House, it cost $180,000. One parishioner wrote a check for $100,000.

"We had no idea what we were doing when we opened the [barbershop] storefront, still don't," Henninger said. "We found out as long as you do something, it will lead to something else. We do a lot of reflection in this parish."

The drop-in center shifted to one part of what is now Demetria House. A safe place for people to sit, talk, have coffee, play cards, do their laundry, pick up a sandwich. And Demetria House came about because when the hungry knocked on the rectory door, Henninger invited them in. The homeless had nowhere to go. She invited them in. They slept in the boiler room.

Meanwhile Corpus Christi noted other currents. The men who came to the barbershop drop-in center sometimes were headed to jail. The parish followed them there. That led to Rogers House, a home for ex-offenders. The house, childhood home of a diocesan priest who gave it to the parish, comes under Jim Smith's overall prison ministry program — parish groups visiting five different prisons.

Advertisement

Callan tells this while jabbing at his breakfast special in Rogers House Restaurant (serving breakfast and lunch only). The parish-owned restaurant is operated by ex-offenders so they can get job experience and filter back into the work force.

"We don't attempt to get them into the food business," said Callan. "That's not what this is about. It's just to teach them how to work. Many have never worked before."

The restaurant was a burned-out former bakery. A bargain at $37,000. A parishioner later wrote out a check.

The parish subsidizes the restaurant. "I'd hate to see this go," Callan said. Its existence also is one more anchor holding the neighborhood together. And its rooms are used by civic groups for meetings.

Ex-offender Kathy, waiting tables, refilled Callan's coffee cup and said she was hoping her jailed and dying husband, Jim, would be able to get into Isaiah House, the parish-run hospice. (He died eight days later, before hospice care could be arranged.)

Building a safe haven

At Demetria House, Henninger found that her mission was people in recovery rather than the overnight homeless. "We kept getting these calls from people in recovery — they were coming out of a recovery facility and didn't have a safe place to go," she said.

Today, Demetria house usually has eight residents plus Henninger. The clientele is referred by inpatient programs. Henninger's interview process is rigorous: The regimen is tough love. Sponsored attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous is mandatory. And the residents — whatever their religious background — have to develop a prayer life or meditation moments appropriate to them.

As Willy, one of the residents, told NCR, "I learned. It works. I'm doing well." And he is, holding down a full-time job while working toward the day when he's independent again.

Resident Al Smith is now night staff person at Rogers House — he's never been incarcerated, but as an AA member he knows that most of the ex-offenders have been drug- and alcohol-addicted. "I can tap into that and being separated from the family. I know what they're going through," Smith said.

Back in the 1970s, one of those around the Thursday night altar was Margaret Wittman. Actually she wasn't so much around the altar as trying to hide behind one of the pillars. "I was afraid. I didn't come from a demonstrative family," she said. "All that hugging and kissing. I said I can't do this. I was hiding behind the pulpit, and people would find me and welcome me and say, 'What's your name?' Finally, I just had to kind of let myself go."

Wittman was at Mass there in 1978 because her mother had died. Her father was too sick to make the long trip up a church aisle for a Mass. The funeral director had suggested the funeral Mass be said at the funeral home.

The local priest refused. The funeral director was a member of Corpus Christi, Wittman's parish as a child. She had gone to school there. Callan said he'd do the Mass at the funeral home. He also invited Wittman to the Thursday evening liturgy.

Today Wittman is the supervising sacristan.

She's also the one who watches for sexist language in the readings and prepares nonsexist readings. Then she has the de-sexed readings laminated for future use. They're known (off the altar) as the Scriptures According to Margaret.

As for the Ramermans, both served in ministry until Jim went back to school for his doctorate and started a conflict resolution service. They bought a home and their two children go to local schools.

Mary Anne became associate pastor.