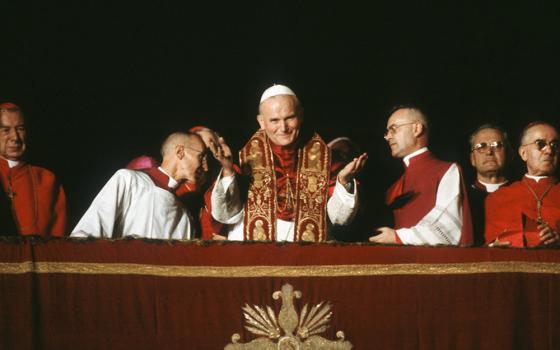

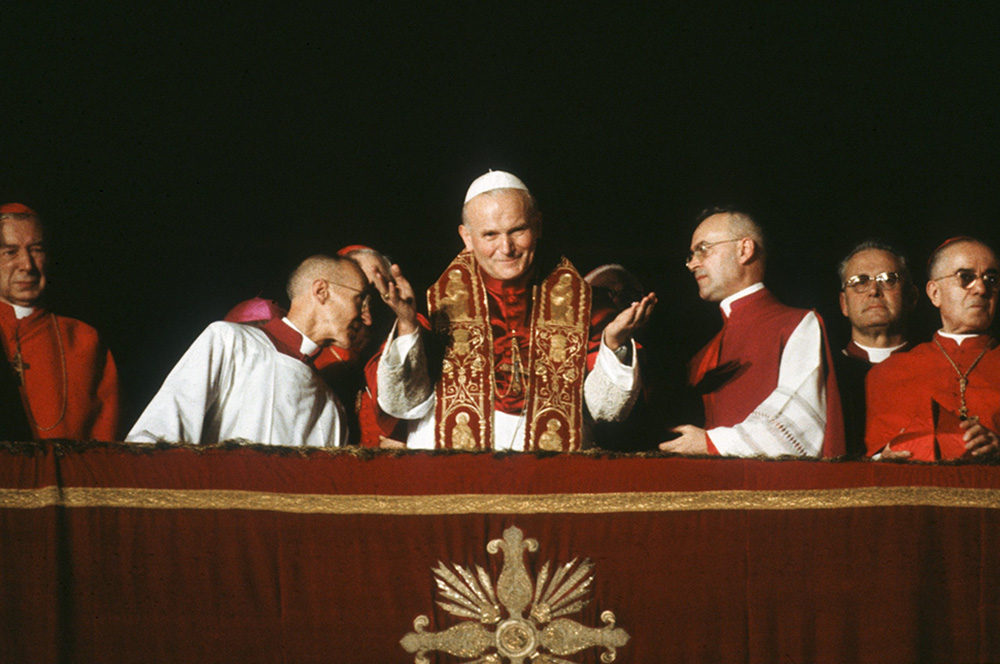

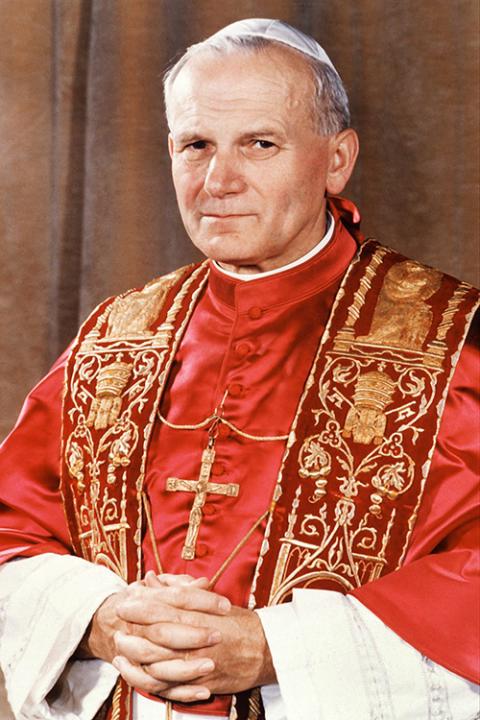

Pope John Paul II appears on the balcony at St. Peter's Basilica following his election to head the Catholic Church on Oct. 16, 1978. (OSV News/Catholic Press Photo/Giancarlo Giuliani)

At the National Catholic Reporter, we along with our fellow Catholics are praying for Pope Francis as he battles bilateral pneumonia.

As we pray, we also contemplate the future of the church. Francis' recent illness at the age of 88 had us thinking about past papal transitions.

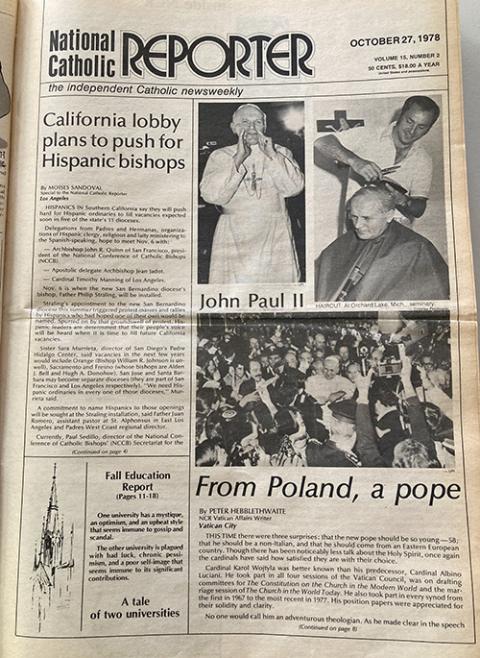

This year as we celebrate our 60th anniversary, we are enjoying stepping into the archives and dusting off our bound print editions to read our previous coverage. This time, we have pulled out the story NCR published after the election of Cardinal Karol Wojtyla in 1978. Pope John Paul II was a triple surprise, as you can read here.

John Paul II: From Poland, a pope

October 27, 1978

By Peter Hebblethwaite

NCR Vatican Affairs Writer

VATICAN CITY — This time there were three surprises: that the new pope should be so young — 58; that he should be a non-Italian, and that he should come from an Eastern European country. Though there has been noticeably less talk about the Holy Spirit, once again the cardinals have said how satisfied they are with their choice.

Cardinal Karol Wojtyla was better known than his predecessor, Cardinal Albino Luciani. He took part in all four sessions of the Vatican Council, was on drafting committees for The Constitution on the Church in the Modern World and the marriage session of The Church in the World Today. He also took part in every synod from the first in 1967 to the most recent in 1977. His position papers were appreciated for their solidity and clarity.

Advertisement

No one would call him an adventurous theologian. As he made clear in the speech the day after his election, he is wedded to the theology of Vatican II and thinks it should be applied still further and developed. He particularly stressed collegiality and its instrument, the Synod of Bishops. Though these would not be called "progressive" views in Holland, in Poland they represent the best and most advanced thinking available.

Cardinal John Krol of Philadelphia, who knows the new pope well, was right when he commented that in the U.S., Vatican II "has meant adaptation rather than spiritual renewal. In Poland they focused on spiritual renewal." Still, Wojtyla organized a synod in his diocese — it is still going on — in which more than 500 groups of 15 to 20 people work together on texts.

In his first speech to the cardinals, Pope John Paul II committed himself to ecumenism without any of the hedging restrictions his predecessor introduced. It is difficult for a Polish Catholic to find a partner in ecumenical dialogue — the Orthodox number 500,000 and move among themselves, while the Protestants number only 200,000.

But the Octave of Prayer for Church Unity has been held in Krakow ever since Wojtyla became archbishop in 1964. Liturgies were celebrated in the Dominican church, with Wojtyla presiding in person, and on the last evening, the service was followed by an agape (love feast) in the medieval Dominican refectory.

One of the most significant stages on Wojtyla's road to the papacy came in 1976 when Pope Paul VI invited him to preach the Lenten retreat for the Roman curia. His discourses were published last year in Italian in a book called Sign of Contradiction. It is classic enough material, but enlivened with literary references to Shakespeare and contemporary authors. But the real importance of the 1976 retreat was that the cardinals of the curia came to know him better and liked what they saw.

As bishop of Krakow in the 1960s, Karol Wojtyla, the future Pope John Paul II, was a prolific writer. He is pictured in an undated photo. (OSV News/CNS file)

Another clue to his election is that three Latin American bishops bought copies of Sign of Contradiction two weeks before the conclave began. They had him on their short list. True, he has said little about the Third World and does not know much about it from firsthand experience — though there is a delightful picture of him with feathered warriors in New Guinea — but a Polish bishop can do nothing about the Third World.

No money may be sent out of the country. Even food and medicine parcels may be stopped and have heavy export duties. Poland's contribution to the Third World has been through her missionaries.

After the indiscretions of the last conclave, lips have been more tightly sealed this time. One hint, however, was provided by Cardinal Avelar Vilela Brandao, a conservative-minded Brazilian, who revealed that in the first ballots the Italian candidates blocked one another, and that a foreigner was needed to get them out of the deadlock. Cardinal Giovanni Benelli of Florence, who at first seemed rather brusque with the journalists, confirmed this when he said: "We did not have the necessary convergence on an Italian candidate. But that does not really matter since there are no foreigners in the church." Cardinal John Carberry of St. Louis unhelpfully said: "I would like to tell you everything. It would thrill you — but I can't."

Pope John Paul II has already conquered the people of Rome. His opening few words, while not having the quicksilver wit of Luciani, delighted them, especially when he apologized — quite unnecessarily — for speaking their language so badly, in hope they would correct the mistake "in your language — no, in our language (Italian)." After that, they cheered everything.

When, the next day, he emerged from the Vatican to visit Bishop Andre Deskur, the Polish head of the Vatican Commission for Social Communications, who is ill in a Rome hospital, their delight was even greater. The pope rode through the streets in an open car and was cheered along the route. Pope John Paul I also had tried to get out of the Vatican but had been advised against it for protocol reasons. Pope John Paul II evidently swept such reasonings aside. He will be his own man.

The front page of the Oct. 27, 1978, issue of the National Catholic Reporter (NCR photo)

He has learned tough-minded independence the hard way. Few priests can have had such an unusual preparation for ordination. Just before World War II, he was a student at the famous Jagellonian University in Krakow (apart from Prague, the oldest university in central Europe). There he studied Polish literature and tried his hand at poetry.

He belonged to a theatrical group called Rhapsodic Theater (a loose translation). They did verse dramas on heroic, medieval themes from Polish history, sometimes in modern dress. They were regarded as avant-garde. When the war came, the theater was abolished, along with all other signs of cultural life, but the group continued to perform in private apartments before groups of 20 to 30 people. Wojtyla belonged to the "cultural resistance movement."

He was by now doubly an orphan. His mother had died when he was a small boy. His father, a non-commissioned officer in the Polish army, died in 1941. His only brother, who was much older, was a doctor who caught an infection from one of his patients and died before the war.

At 21, the young Karol Wojtyla was on his own. He found work in the Belgian-owned Sollvay chemical factory (it still exists in Krakow, but under a different name) partly to have an arbeitskarte (a work permit). Anyone caught without a work permit risked deportation to slave labor camps.

But in 1942 he vanished from his factory and was not seen until after the war. During this time he was in the archbishop's residence in Krakow pursuing his philosophical and theological studies. He and four other students there were directed by Cardinal Adam Sapieha (who was known as Prince Sapieha because he was a prince by birth and a "prince of the church"). For security reasons they never left the palace. From this period the rumor of his supposed marriage and widowhood dates. It is false.

Wojtyla was ordained in 1946 and managed to leave Poland for Rome, where he did a study of St. John of the Cross at the Angelicum University in Rome, under the direction of the French Dominican, Father Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, who was famous for the intransigence of his Thomism.

But this influence was balanced by his doctorate at the Catholic University of Lublin Poland, which was a study of Max Scheler (1874-1928), a Catholic philosopher with leanings toward existentialism and personalism (phenomenology). Wojtyla is a serious reader who likes to keep up with all the latest books.

Pope John Paul II is pictured in a Vatican photograph following his election Oct. 16, 1978. Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland, became the 263rd successor of St. Peter. (CNS file)

It was the time of Stalinism. Wojtyla was successively assistant priest and pastor and also taught theology in secret (the faculty of theology in Krakow had been suppressed). He kept a low profile. He wrote a good deal of poetry in this period.

His poetry was published in the weekly publication Znak (Sign), the movement of Catholic intellectuals in Poland. He never signed any of the poems, because he thought this would be incompatible with his priestly ministry. He used instead the pseudonym of Andrzej Jawien.

Jerzy Turowicz, the editor of Znak then as now, told me the poems were long, written in free verse, and dealt with philosophical and moral themes. They were certainly not pious, and not always religious. Znak has high standards and rejects 90 percent of the poetry it receives.

But why Andrzej Jawien? This was the name of the hero of a popular pre-war novel, The Sky in Flames, written by Jan Parandowski. It was the story of a young man who lost his faith. (He recovered it in a later post-war novel.)

After this unconventional background, the rest of the Wojtyla story is less dramatic, though there were the usual struggles with the authorities, normal in Communist countries. The Russians had insisted — against all economic logic — on building a new town, Nova Huta, where the new socialist individual was to be forged along with steel. Revolts broke out in 1966 when the authorities tried to stop the building of a church. In 1977 Wojtyla opened that new church, which rises like a vast ship.

The idea was that Nova Huta should counteract the sleepy Austrian-Hungarian empire provincialism of Krakow. It failed. The people of Nova Huta are saved from boredom in their grey city by the closeness of Krakow with its cafe society and satirical theaters.

Wojtyla was named auxiliary bishop of Krakow in 1958 and became archbishop in 1964. Turowicz told me Wojtyla wanted to remain in the two-room flat he had as auxiliary bishop when he became archbishop. He managed to hold out against the vicar general for four weeks until he came home one day to find that the vicar general had removed his belongings into the episcopal palace.

Wojtyla turned the palace into a hive of activity. Every month he organized two-day symposiums for young people, actors, workers and priests, and always took part himself. His curia thought he should have been busy about other things. Every morning he received visitors on a first-come first-served basis. He was known familiarly among Krakow students as "uncle."

Many inaccurate reports have circulated that he was appointed cardinal to counterbalance the influence of Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski, primate of Poland. Wojtyla is 20 years younger than Wyszynski, does not share his anti- intellectual approach and does not reduce theology to Mariology, but they have remained friends, and Wojtyla has always remained perfectly loyal to Wyszynski. The unity of the Polish episcopate is the basis of their entire policy.

Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski of Warsaw and Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, the future Pope John Paul II, and Cardinal John Krol of Philadelphia are pictured at a ceremony in Brzezinka, Poland, Oct. 15, 1972. (CNS photo)

Questions are being asked already about the political implications of the election. If the cardinals wished to embarrass Polish President Edward Gierek, they could not have found a better way to do so. And yet Gierek, as a patriotic Pole, will not be wholly displeased.

The real problem will come if Pope John Paul II makes a return visit to Poland. He already has indicated he would like to go back for the May 8, 1979, celebrations to mark the ninth centenary of St. Stanislaw, an early bishop of Krakow who was murdered in circumstances similar to those of Thomas a Becket in Canterbury. The question is whether a Polish pope could go back home without a demonstration of popular feeling that could be explosive. The idea that Our Lady is queen of Poland makes a political point: the current rules are temporary usurpers.

Italians, on the other hand, see the implications for their own situation, and are anxious about the future of the "historic compromise," an agreement between the Christian Democrats and Communists. At the 1977 synod, Luciani quoted a ''Polish bishop," who had remarked to him that Italian Communist party leader Enrico Berlinguer's promises of respect for the church and political pluralism were "no more than fine words." The Polish bishop was Wojtyla.

The rest of the church will be more interested in his approach to others controverted questions. There is little joy for progressive. His book, Love and Responsibility, defends Humanae Vitae, which, he says, "provides luminous and explicit norms for married life."

To those who talk about a crisis in the priesthood, he cites the example of Blessed Maximilian Kolbe, the Franciscan who gave his life in Auschwitz to save the father of a family. Wojtyla has the traditional Polish attitude toward women, though slightly softened by his regard for Blessed Hedwig, the queen of Poland who founded the Jagellonian University in the late 14th century.

But past performance is not necessarily a sure guide to future actions. Pope John Paul II is a thinker. He already has shown he has great respect for the local churches. His pride in the ancient diocese of Krakow will enable him to respect the rights of other churches, including the newer ones.

It is difficult to imagine, for example, that he would want to interfere with preparations for the deferred meeting of Latin American bishops, now that they have revised the documents in the light of the storm of criticism to which the previous draft was subjected.

Perhaps the best symbolic expression of Wojtyla's new style came last Wednesday when he spoke to the college of cardinals. Instead of blessing them at the end of his speech, he asked them to bless one another. He could hardly have found a better way of saying he will think of himself as not above his fellow bishops, but with them.

To read more about the early years of NCR, see the recently published National Catholic Reporter: Beacon of Justice, Community and Hope. You can learn more about the book at NCRonline.org/ncrbook, which includes links to outlets where you can buy the book in hardcover, paperback or e-book editions.