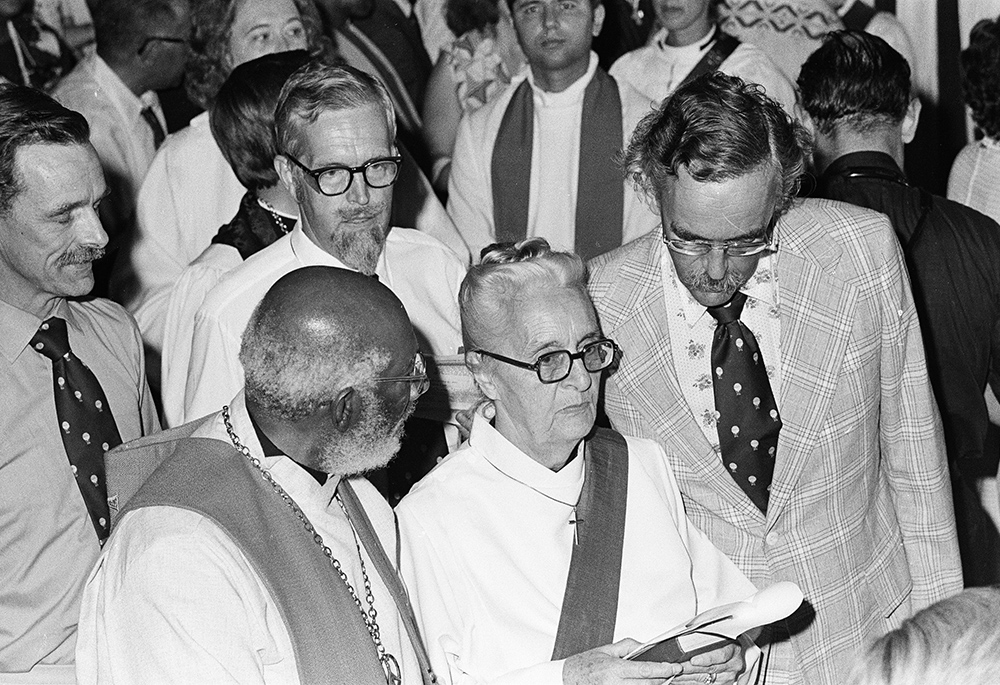

Jeannette Piccard is pictured with (clockwise, left to right) the Rev. Denzil Carty and her three sons Donald, John and Paul, during the processional at the Church of the Advocate, July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia. There she and 10 other women became the first women ordained to the Episcopal priesthood in the U.S. (Brad Hess)

That morning, she was on her way to becoming the first woman to enter the stratosphere, but even then she must have known that she was only killing time, waiting for the moment when she would find a way to fulfill the calling that she had voiced as a child, a revelation, according to biographer Sheryl K. Hill, that had sent her mother running from the room in tears.

Back in those childhood days, when Jeannette Piccard walked by the mantle in her home, she would pass the urn holding her twin sister Beatrice's ashes. She had watched her sister's dress catch fire while the two of them were playing with an older sister's toy stove. She had seen the flames engulf her, had remembered thinking, "She won't be able to live." Her granddaughter Kathryn later told me that Jeannette never recovered from the tragedy and had spent her entire life traumatized by it.

I once asked Jeannette's son Donald about Beatrice and the effects of her death on his mother. "I remember when she was in her 50s," he said, "and she was visiting the doctor in Minneapolis. The doctor was taking her pulse. He took it resting, then had her move around and took it a second time, and then he took it resting again. The third time is supposed to be the lowest of all, but hers was elevated. The doctor didn't understand. Jeannette thought for a moment, then she said, 'Did you hear that fire truck go by?' That's what had raised her pulse, the reminder of the fire truck. They were very, very close twins."

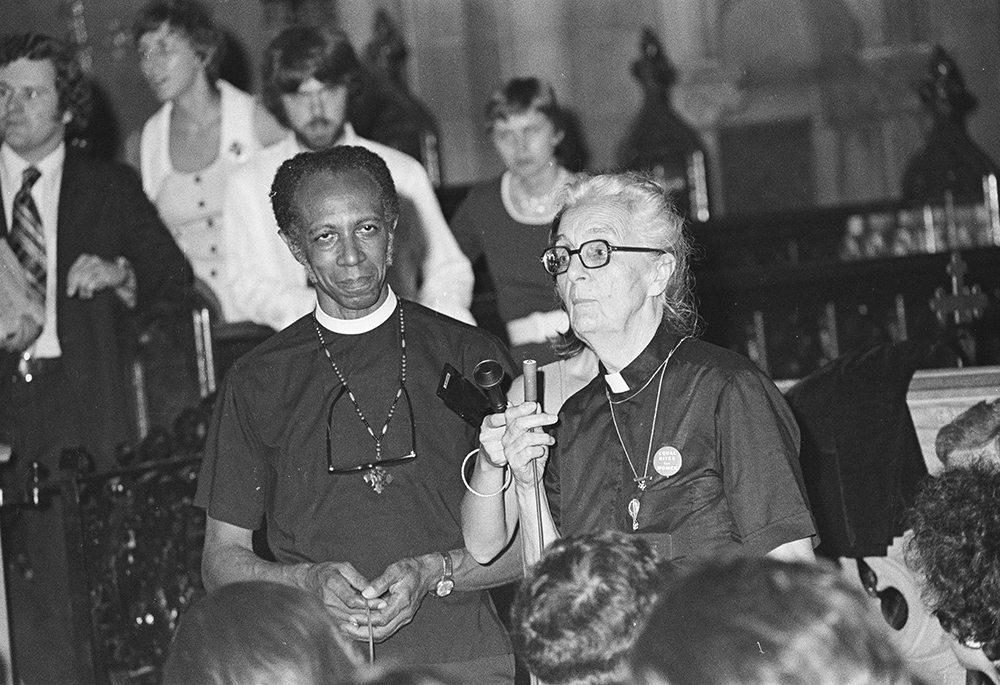

Jeannette Piccard speaks to reporters after the ordination service in which she and 10 other women became the first women ordained to the Episcopal priesthood in the U.S., on July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia. The Rev. Paul Washington, rector of the Church of the Advocate, stands to her left. (Brad Hess)

Yet, the trauma had not paralyzed her when the cottage where her children were sleeping caught fire. Kathryn told me this story: The family was staying in Rhode Island, visiting Jeannette's mother who owned vacation property there. After the children had been put to bed on the second floor of the cottage, Jeannette walked next door to the main house on the property and as she poured a cup of coffee, she looked over at the cottage and saw that it was in flames. She rushed back, bolted up the stairs, and managed to move the children to the roof, where she dropped them into the arms of a man who had pulled over his car when he saw the fire. Then Piccard herself jumped to the ground. The specifics of the story vary slightly according to the family member telling it, but the essence of the story remains consistent.

Kathryn believed that the children should never have been alone in the house in the first place, but then she hadn't been the first to question Piccard's skills as a mother. Jeannette noted that the National Geographic Society had made that point years before, in 1934, when she had decided to pilot her scientist husband Jean Piccard into the stratosphere — in a balloon named the Century of Progress — so that he could perform experiments on cosmic rays. The Piccards had approached the society for funding for their flight but had been declined.

In her autobiographical notes held at the Library of Congress, Jeannette wrote, "With virtue drip[ping] from their lips," the society "would have nothing to do with sending a woman and a mother on so dangerous an expedition!" About her decision to pilot the balloon, she added, "When one is a mother … one does not risk life for a mere whim. One must back up emotions by cold reason. One must have a cause worthy of the danger. In times of war one sacrifices self and children for country. In times of peace the sacrifice is made for humanity."

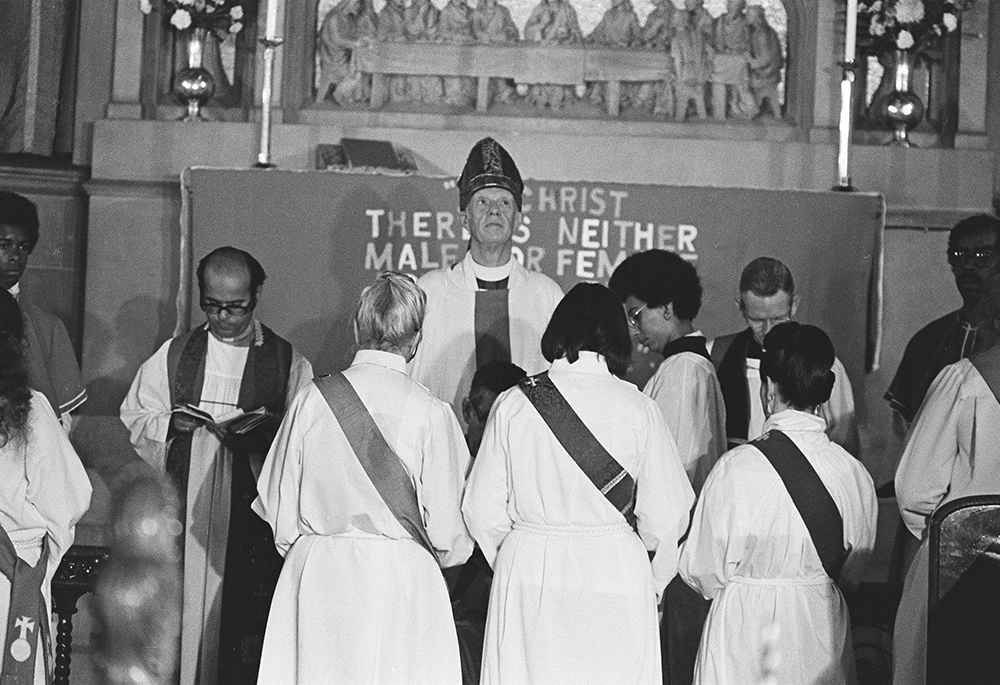

Jeannette Piccard kneels in the center, third from right, during the ordination service at Church of the Advocate, July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia. Piccard was ordained to the Episcopal priesthood 40 years after her flight into the stratosphere. (Brad Hess)

Before the Piccard flight, only a handful of U.S. pilots had attempted taking a balloon into the stratosphere. In 1927, Capt. Hawthorne C. Gray was forced to parachute from his balloon when he was unable to slow its descent. He went up again six months later but was found dead in the gondola when the balloon landed. In 1933, another attempt ended abruptly when pilot Thomas Settle aborted the mission after 20 minutes, though he did successfully enter the stratosphere on his next flight. In July 1934, three months before the Piccard flight, three Army officers parachuted from the Explorer as the balloon began to tear apart over the fields of Nebraska. One of the officers became trapped in the escape hatch but managed to free himself only moments before the remains of the balloon exploded.

Even so, the Piccards told their young boys, John, Paul and Donald, that the flight would be no more dangerous than if they were crossing the street. Still, the couple had hoped it would take place during the summer, when the boys were away at camp, but a series of delays moved the launch to a cold October morning, to Ford Airport in Dearborn, Michigan.

A newsreel shot that morning shows the Piccard family next to the round gondola, both parents wearing tweed coats and smiling at their sons. Jeannette stands in the middle with one arm wrapped around her boys and the other around her husband. Bystanders and on-sight specialists, nervous that Jean had chosen to use explosives to disconnect the lines holding the balloon, were not nearly as relaxed about the coming flight. The presence of 700 cylinders of hydrogen only heightened their concerns, according to David DeVorkin in his book Race to the Stratosphere: Manned Scientific Ballooning in America (though NASA would later adopt the practice of using pyrotechnics in its space missions).

Jeannette Piccard, then training for a flight into the stratosphere with her husband, Professor Jean Piccard, is shown with her husband, at right, and Edward J. Hill, left, well known balloonist, just before they took off on a training flight at Detroit, on May 16, 1934. (AP photo)

As the launch began, the charges failed to detonate simultaneously, causing the balloon to separate unevenly and drift dangerously close to rows of cars and trees. Jeannette released some of the ballast to lighten the balloon, and a group of men rushed forward to push it upwards. Then away it went, carrying the two — and the family's pet turtle Fleur de Lys — while the Piccard boys stood waving below. As they rose above the crowd, Jeannette heard one of her sons yell, "Goodbye, Mother."

During the balloon's ascent, Jeannette realized that a valve rope was out of place. To correct it, she stood on a small shelf and reached outside the gondola — which looked like a giant black and white fishing bobber — to try to reposition the rope. From the knees up, her body was exposed to the outside, and it was then that she slipped on tiny bits of round lead ballast that had rolled under her feet. She was able to regain her balance and move the rope. While the cloud cover had blocked her view below, she later realized that she had probably been over Lake Erie at that point and that had she fallen, the water would have rendered her parachute virtually useless.

Advertisement

Then there were the heavy winds and the loss of radio contact and the cloud cover that still had not dissipated as predicted. After reaching 57,579 feet and taking a series of measurements, the Piccards began their descent, though they had no idea where they were located. A landing over water would have likely led to their drownings. They were also unable to measure how quickly they were descending. Jeannette later described her thoughts at that moment in an article for The New York Times: "Were we traveling two miles an hour or 200? Were we going east or north or south? Were we over Ontario, or Lake Erie, or already over the ocean?" According to her newspaper account, she attempted to slow the balloon's landing by releasing sandbags and a heavy battery connected to a parachute. Nothing worked.

After bursting through the cloud bank, the Piccards found themselves heading toward a farmhouse. They dropped lead bags from the balloon, which sent the balloon flying back into the clouds. Jeannette attempted to make adjustments, but their speed once again accelerated as they were propelled toward a stand of trees. Her efforts to swing the balloon in a different direction were unsuccessful, and it became entangled in branches.

They were stuck, looking at each other — as Jeannette recalled — "like Tarzan and his mate" when they heard a popping sound and felt the gondola shifting. "Bend your knees," Jean yelled, and the two of them fell another 15 or 20 feet to the ground. Jean sustained small fractures in his ribs and ankles. Minutes later, he sat covered in a blanket, away from the crowd that was gathering. Fleur de Lys had apparently survived the trip unscathed.

The details of Jeannette's actions at the landing depended on the journalist reporting the story. She was observed powdering her nose, smoking a cigarette, joking with reporters, checking on the turtle, and/or eating a sandwich. She voiced frustration over the way she had brought down the balloon and over the fact that pieces of it were hanging in the treetops, but she managed to make light of the situation, saying that she had created a "mess" even as she had hoped to land on the White House lawn. They actually landed in Ohio, outside the small community of Cadiz, population approximately 2,500.

Piccard later reflected in a University of Chicago Magazine article on the experience of being in a balloon, comparing it to being in "a magnificent cathedral," where you could "almost feel like part of eternity." And her metaphor brings us back to her childhood, back to her terrified mother running in tears from her room after Piccard had spoken truthfully about her dreams. And it was not her daughter's being the first woman flying into the stratosphere (with only an eighth of an inch of magnesium alloy between her and an 11-mile drop) that had frightened her mother. What had frightened her that night was Jeannette's revelation that she wanted to be a priest, an Episcopal priest. Granted, it would seem on the surface that a young girl's desire to become a spiritual leader should hardly be the sort of news to send a mother running away in despair, particularly a mother who had endured multiple heart-wrenching losses. The household mantle from Jeannette's childhood held the ashes of another daughter as well.

Jeannette Piccard, Betty Bone Schiess, and Alla Bozarth (kneeling) are pictured with Bishop Edward Welles (center) during the ordination service at the Church of the Advocate, July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia. The 11 women ordained that day became known as the Philadelphia Eleven. (Brad Hess)

It is difficult to conclude with any degree of certainty why Piccard's mother found this news distressing, though perhaps she could have predicted what was in store for her daughter as she attempted to follow her calling to the priesthood. The Episcopal Church did not easily make the transition to allowing women in the priesthood. The church had fallen into a dysfunctional pattern of studying the issue, concluding that there were no theological reasons that women could not be priests, refusing to act on their conclusions, and then calling for more study.

As two women deacons noted at the time, "The church has debated and referred the question for so long that it is acquiring a certain amount of expertise in putting it off." This process went on for 50 years until finally, on a "blistering" hot July day in 1974, 11 women who had grown tired of waiting would force the Episcopal Church's hand by becoming ordained by three willing bishops (with the presence of a fourth supporting bishop). The women became known as the Philadelphia Eleven. Piccard was one of the 11 and at the age of 79 (40 years after her flight into the stratosphere) took her vows to become a priest.

Each of the women experienced their own separate hells as adversaries reacted to the ordinations, but as a group they were vilified in numerous ways, including through letters, phone calls, telegrams, editorials, sermons and speeches. They were accused of being part of "Lucifer's coven" and of turning the church into a "cesspool" of "whoremongers and pimps." One letter writer referred to the women as "heretics," "prostitutes," "fornicators," "n****** [the women were white, but racism made its way into the criticisms]," "long-haired depraved bastards-bitches in dope," "VD infested," "mongrels," "women's libbers," and "pretenders on the prowl."

A bishop from Kentucky said that as a result of their actions he would feel free to ordain the horse Secretariat, who had at least followed the biblical command of being fruitful and multiplying. One of the women received fishing line and was instructed to hang herself with it. They were compared to the Watergate conspirators and told that they were all "egotists" and a "discredit" to the church.

They were even blamed for the death of a bishop. The Episcopal bishop of Maine, Frederick Wolf, had called for a meeting in New York for the purpose, in part, of discussing how to deal with the women. The Episcopal bishop of Louisiana, Iveson Noland, was on Flight 66 on his way to attend the meeting. As the plane was landing at John F. Kennedy International, wind shear from a thunderstorm caused the pilot to lose control of the aircraft. It crashed on the runway and burst into flames. Over 100 passengers were killed, including Noland.

A week later, Wolf released a public letter blaming the women for Noland's death. The response to Wolf was immediate. One male priest wrote that Wolf might as well have blamed the Wright Brothers. Piccard wrote to Wolf arguing that he should not "flagellate" himself for calling the meeting: "I cannot believe that God struck down a whole planeload of people just to prevent Bishop Noland from participating in a meeting of the Council, whatever its agenda may have been."

Although these women (and four others who had been ordained in Washington, D.C.) had graduated from schools such as Radcliffe, Smith, Brown, the University of North Carolina, Northwestern, the University of Chicago, Union Theological Seminary, Cornell and Episcopal Divinity School, they were considered by their opponents as improper matter for ordination. Might as well ordain a piece of wood or a rock or even a monkey in a tree as to ordain a woman, their detractors argued. And because the women could not and would not know their place within the church hierarchy, they were blamed for tearing the church apart and for taking it down the inescapable road of schism.

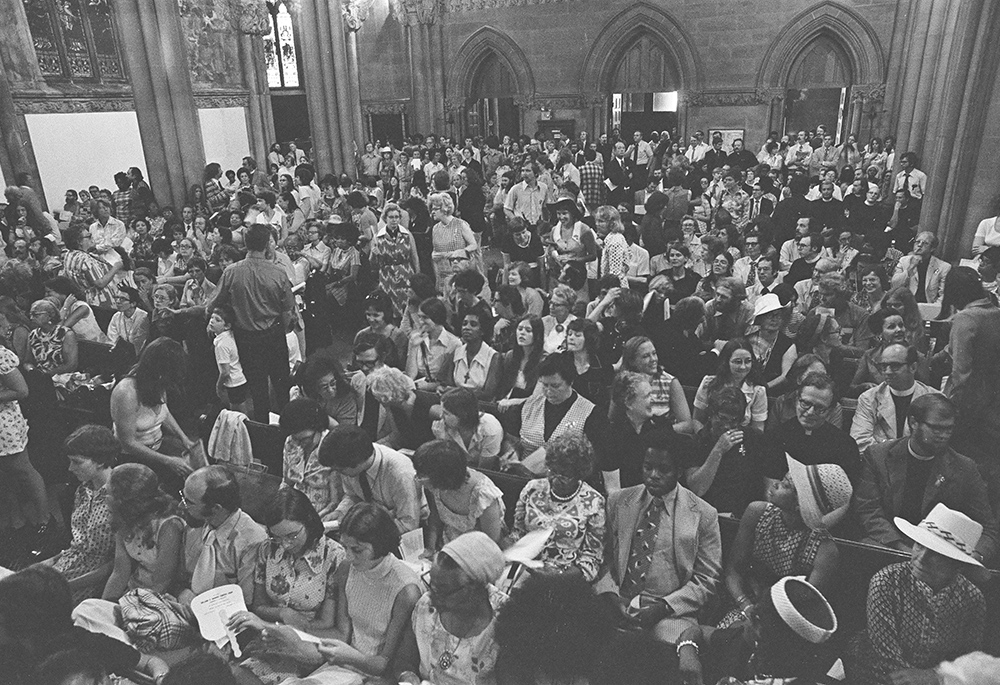

The congregation is pictured attending the ordination of 11 women priests at Church of the Advocate, July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia. (Brad Hess)

Their story did not play out on a small stage but became an "extra, read all about it" moment in American history. For a two-year period between 1974 and 1976, stories appeared in both national and local newspapers, from The New York Times to The Washington Post to The Kansas City Star to The Los Angeles Times. The national nightly news programs reported on the ordinations. Three of the women appeared on "The Phil Donahue Show." International papers like The Guardian ran stories. The BBC sent representatives to the ordination service. In fact, over 200 media representatives came to the predominantly African American Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia to cover the story. And 2,000 people arrived to be part of the congregation.

John Allin, the presiding bishop at the time, sent the women telegrams literally begging them to abandon their plans. He had convened a meeting with the women earlier in the year in Connecticut. It had not gone well, with the women finding him "insensitive" and "insulting." He informed them that folks from his home in Mississippi believed the women wanted to be priests so that they could wear fancy clothes with "ruffles at the wrist." Carter Heyward, one of the 11, recalled that during the meeting Allin kept referring to the women as girls. "Jeannette," as Heyward tells the story, "was sitting there with her cane when she finally banged it on the floor and said, 'No, sonny boy, not a girl. I'm old enough to be your mama! You're the age of one of my sons.' Then Jeannette," Heyward continues, "turned to one of the other women and added, 'Actually, he's the age of my miscarriage.' "

Regardless of the efforts of Allin and most of the other bishops, the ordinations were to go ahead. The Philadelphia police came by the busload and parked down the street. A group of plainclothes officers were scattered among the crowd. Buckets of water were lined up along the walls of the church in case of bombs or fire, a group from the LGBTQ community served as part of the security team, and members of the media scrambled for photographs. The women recalled being blinded by large television lights as they moved through the procession. An opposition group had attempted to take out a temporary injunction to stop the ordinations, but the judge informed the opponents that he was refusing to hear the arguments and suggested that the church handle it in its usual manner: "at the stake." It would not be the only reference to witches in relation to the event. One protestor stood and claimed that the ordination of women was a perversion. He could, he said, smell the sulfur in the air. The fear, according to the editorial in The Witness written for the 10th anniversary of the ordinations, was that when "you mix women and rituals, you get witchcraft. And they burn witches, don't they?"

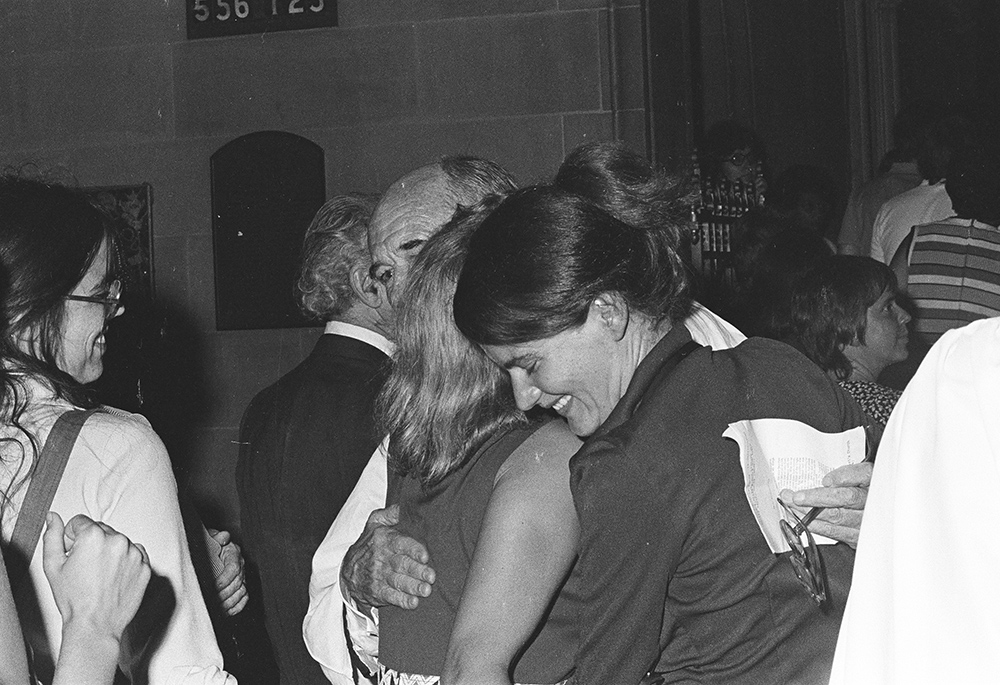

Congregation members respond to the ordinations at Church of the Advocate, July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia. (Brad Hess)

Even with the protests, the crowd of 2,000 was overjoyed. Old audio tapes of the event record laughter and applause that is at once jubilant, euphoric, relaxed, contagious, and delightfully raucous. Responding to the atmosphere surrounding the service, Charles Willie, who delivered the sermon, described the day as "strange and enchanting."

The women ordinands, more than half of whom were in their 20s and 30s, had decided that Jeannette should be the first among them to be ordained since she had been the one waiting the longest amount of time. Jeannette's age did not go unnoticed by one of the protestors who complained that it would be a travesty for her to receive a pension. The Piccard boys had grown into men and according to reports from those sitting near them, did not take well to the protestor's point, nor did many in the congregation who fervently booed him.

Jeannette was unable to secure a parish of her own because of her age and because those positions were difficult to come by for the 11, but she spent the last years of her life as an unpaid assistant ministering to the poor and elderly, delivering sermons, and concelebrating the Eucharist. The opponent in Philadelphia need not have worried himself over her pension.

She was also a popular speaker and remained active in social justice causes. Toward the end of her life, a reporter asked her about her goals and Piccard answered, "You won't like this, but I've lived my life. I want to die and get on to the next thing." On May 17, 1981, Piccard died of cancer at Masonic Memorial Hospital in Minneapolis.

This year marks several anniversaries in Piccard's life: July 29 will be the 50th anniversary of the ordinations in Philadelphia and Oct. 23, the 90th anniversary of her flight into the stratosphere. It's undoubtedly a year to celebrate the courage she showed throughout her life and to remember her accomplishments and the tenacity she showed during her time here on earth. Even so, as I took a late evening walk not long ago and looked into the flickering stars, I couldn't help but wonder what Jeannette found in that "magnificent cathedral" as she boldly "[got] on to the next thing."