(Unsplash/Samuel Lopes)

In 1950, the renowned German theologian and theological peritus at the Second Vatican Council, Jesuit Fr. Karl Rahner, published a short article titled, "A Faith That Loves the Earth," in the journal Geist und Leben. The focus of his reflection was an attempt to say something about the joyful mystery of Easter, which is, as he put it, "the most human message of Christianity." And yet, Rahner notes, this "is the reason we have such a hard time understanding it. For what is the most true and obvious, in short, the easiest, is also the hardest to live out, to do, and to believe."

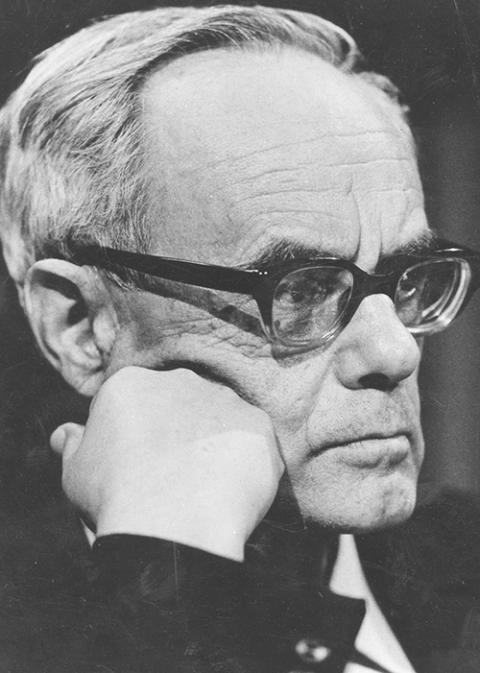

Jesuit Fr. Karl Rahner (NCR file photo)

Rahner emphasizes our creatureliness, finitude and precarity as human beings, and reflects on the importance of Christ's full participation in that same human experience we all share. The mystery of Easter is the summation of God's incarnational expression of love — God's emptying God's self of all power and control (Philippians 2:6-11) in order to participate in the full range of creaturely existence, drawing near to human and nonhuman creatures, becoming a part of creation like us.

Precisely as one who is also fully divine, Christ's participation in the created order shows forth not only the inherent goodness of creation — something the second-century theologian Irenaeus of Lyon worked hard to communicate millennia earlier — but also the capacity of creation to receive the greatest good God could bestow to it, the gift of God's very self. In this way, what we celebrate at Easter is the full affirmation of the presence of the divine in the world and the hope we have of new life to come.

Rahner writes: "His resurrection is like the first erupting of a volcano, which shows that the fire of God is already burning inside the world and its light will eventually bring everything else to a blessed glow. He is risen to show that it has already started."

Easter is not only about the resurrection of one individual, but it is also about the whole of creation and salvation history, which are inextricably united. Easter is not only significant for us human beings alone, but also for all God's creatures. In a particularly moving passage, Rahner explains:

Christ is already at the very heart of all the lowly things of the earth that we are unable to let go of and that belong to the earth as mother. He is at the heart of the nameless yearning of all creatures, waiting — though perhaps unaware that they are waiting — to be allowed to participate in the transfiguration of his body. He is at the heart of earth's history, whose blind progress amidst all victories and all defeats is headed with uncanny precision toward the day that is his, where his glory will break forth from its own depths, thereby transforming everything.

And because Christ is at the heart of all of creation, we can say that it is not only Easter but all of Holy Week that has significance for more than just humanity alone.

"The Entry into Jerusalem; Christ riding on a donkey towards an arched city gate; an elderly man spreads out his cloak on the road," from "The Passion of Christ", after Dürer, circa 1500-34 by Marcantonio Raimondi (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Take Sunday's celebration of Jesus's arrival in Jerusalem. Nonhuman creatures, animals like the donkey upon which he rides and plants like the palms cut down and laid on the path before him, play a key role in the final chapter of the paschal mystery.

When we grasp those palms in our hands this weekend, and hold them up with shouts of "Hosanna" then raise them to be sprinkled with life-giving water, what thoughts enter our mind? Do we think about what significance there might be for the rest of creation in what we commemorate this week? Do we recognize the way nonhuman creation participates in the event of Christ's arrival?

What about Holy Thursday? The institution of the Lord's Supper — what the Second Vatican Council called the "source and summit" of our faith — is fundamentally about a meal shared by Jesus Christ with those women and men closest to him. They took "fruit of the earth and work of human hands," as our eucharistic prayer reminds us, and consumed it as we do all food.

This photo represents Renaissance painter Tintoretto's "The Last Supper." (CNS/Courtesy of Holy See Pavilion Press Office)

The intimacy of the eucharistic meal is obviously about the sacramental presence of Christ drawing near; of God becoming "closer to us than we are to ourselves," as St. Augustine famously described. But it is also about real bread and real wine, which began as wheat and water and grapes, and which nourishes and becomes part of us as all our food does.

Advertisement

It can be easy to overlook the ecological significance of the Eucharist, but as Pope Francis has taught in "Laudato Si', On Care for our Common Home," the Eucharist has cosmic implications:

Indeed the Eucharist is itself an act of cosmic love: "Yes, cosmic! Because even when it is celebrated on the humble altar of a country church, the Eucharist is always in some way celebrated on the altar of the world." The Eucharist joins heaven and earth; it embraces and penetrates all creation. The world which came forth from God's hands returns to him in blessed and undivided adoration: in the bread of the Eucharist, "creation is projected towards divinization, towards the holy wedding feast, towards unification with the Creator himself." Thus, the Eucharist is also a source of light and motivation for our concerns for the environment, directing us to be stewards of all creation.

When we say "amen" to "the body of Christ," may we also say "amen" to our interconnectedness with and interdependence on the rest of creation, recognizing that the Word first became part of that creation in the Incarnation and continues to draw near to creation in the transformed food we consume at Mass.

Pope Francis is pictured through flowers as he celebrates Easter Mass in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican in this April 5, 2015, file photo. It can be easy to overlook the Eucharist's ecological significance, writes Daniel Horan, but as Francis has taught in "Laudato Si', On Care for our Common Home," the Eucharist has cosmic implications. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Rahner makes the point that even Christ's death has environmental significance, thereby signaling the ecological importance of Good Friday. He explains:

Especially because he died, he belongs to the earth, for putting someone's body into earth's grave means that the person (or the soul, as we would say) who has died enters not only into relationship with God but also into that final union with the mysterious ground of being, where all space-time elements are tied together and have their point of origin. In his death, the Lord descended into the lowest and deepest region of what is visible. It is no longer a place of impermanence and death, because there he now is. By his own death, he has become the heart of this earthly world. …

When we say 'amen' to 'the body of Christ,' may we also say 'amen' to our interconnectedness with and interdependence on the rest of creation.

In addition to reflecting on the agonizing death of an innocent man executed by the state, which continues to unveil the radical injustice of the death penalty and the culture of death reflected in support for capital punishment today, perhaps we might also reflect on the ecological implications of Christ's death.

Rahner suggests that we think about the present and future time as "still Holy Saturday until the last day, which will be the day of Easter for the entire cosmos." He adds that Easter calls us forward "as a loving faith that allows us to be brought along on this unimaginable journey of all earthly reality headed toward its own glory, a journey that started with the resurrection of Christ."

As we commemorate the paschal mystery this Holy Week, may we also remember that we are "children of this earth," as Rahner puts it. And may the creatureliness that we share with all of God's creation and with the Word incarnate, challenge us to also consider this sacred time of year through ecological lenses.