Boston Cardinal Bernard Law comments on the proposed "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People" in 2002 in Dallas as the U.S. bishops deliberate on their national response to the clergy sexual abuse crisis in Dallas. (CNS /Bob Roller)

For those trying to understand the legacy of Cardinal Bernard Law, Donna B. Doucette, executive director of Voice of the Faithful, may offer the most useful insight.

Doucette's organization grew out of the revelations of clergy sexually abusing children and its cover up that forced Law out of Boston in 2002, ripped the lid off a simmering cauldron of scandal, and made the sexual exploitation of children by clergy an issue of global concern. She says Catholics should learn three basic lessons from Law's legacy: "absolute power corrupts absolutely," "secrets destroy" and, for those interested in reforming church structures, "trust but verify."

Law died in Rome Dec. 20, 15 years after resigning as archbishop of Boston.

In the winter and spring of 2002 as the public began to learn the tragic, awful truth of how clergy had sexually abused minors, some 25 parishioners gathered at St. John the Evangelist Church in Wellesley, Massachusetts, offering to provide support and counsel to the archdiocese and the cardinal.

Within weeks, the group had swelled into the hundreds, but "they learned that Cardinal Law didn't want help from the laity," said Doucette. In retrospect, she said, it was because Law knew more disclosures of failure on sex abuse policy would eventually become public. It was becoming clear that church leaders had deliberately and systematically covered up these horrendous crimes for decades.

"Cardinal Law was an illustration of how systemic corruption had taken hold of the hierarchy," she said.

Absolute power corrupts absolutely

The obituary NCR ran the day Law died identifies him as "disgraced former archbishop of Boston," but it also carries the line: "Law had been expected to leave a far different mark on the church." That sentiment was carried in official statements and by those who knew him well.

"It is a sad reality that for many, Cardinal Law's life and ministry is identified with one overwhelming reality, the crisis of sexual abuse by priests. This fact carries a note of sadness because his pastoral legacy has many other dimensions," said his successor in Boston, Cardinal Sean O'Malley Dec. 20.

Cardinal Bernard Law, second from right, is pictured during a 1969 march to the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee, for a memorial service for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (CNS file photo)

Ordained in 1961 for the Diocese of Natchez-Jackson, in Mississippi, Law became a champion for the rural poor and the civil rights movement and received death threats for that work. He was a pioneer in ecumenical relations, which took him in 1968 to his first national office in the U.S. bishops' conference.

His first episcopal appointment was to the sprawling, rural Diocese of Springfield-Cape Girardeau in southern Missouri, at age 42. His second episcopal appointment was as archbishop of Boston, at age 52. He would become a cardinal at age 53.

Bishop Christopher Coyne of Burlington, Vermont, was ordained a priest of the Boston archdiocese two years after Law was appointed there. In 2002, as the abuse scandal began to engulf Boston, Coyne was named archdiocesan secretary for communications and became the principal spokesman for the archdiocese.

Coyne didn't return calls to NCR for comment, but he wrote about Law's passing on his personal blog, bishopcoyne.org, saying, "I entrust his soul to God's unending mercy."

"The world at large will rightly have much to say at Cardinal Law's passing from this life," Coyne wrote. "Like each of us, the measure of his days had its fair share of light and shadows."

From Boston, which was then the fourth largest diocese in the country, Law's reach and influence spread. An intervention he gave at a bishops' synod in 1985 is credited with leading to the development of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. He maintained close relations with bishops in Mexico, Perú and Bolivia. He became a key interlocutor in Cuba, shuttling messages between the U.S. church, the Cuban church and the Vatican. He met with Fidel Castro eight times. He had the ear of Pope John Paul II and had great influence in naming U.S. bishops.

He also had great influence in the political arena. It has been reported that when President Ronald Reagan's administration, looking to make budget cuts, was contemplating classifying ketchup as a vegetable in the school lunch program, Law called to complain, and his call was put through to the president aboard Air Force One. He had a long, close relationship with the George W. Bush family and was a frequent visitor to the White House.

But as the light of his influence and power rose, so did the shadows.

In the 1980s, as Law was solidifying his position as a national and international ecclesial and political power. Jesuit Fr. Tom Reese was researching and writing his trilogy of books — Archbishop: Inside the Power Structure of the American Catholic Church, A Flock of Shepherds: The National Conference of Catholic Bishops and Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.

Advertisement

Writing about Law Dec. 21, Reese observed: "With this power and influence came a growing arrogance that demanded others, including bishops, defer to him. Rather than trying to persuade his fellow bishops, he did end runs around them by going to Rome to get his way. Bishops did not appreciate this and responded by voting him down for conference offices, including president."

The extent to which Law would go to protect the powerful institution of the church came to light in January 2002. An investigative series of articles by The Boston Globe and the release of court documents from the criminal trial of a priest of the archdiocese, John Geoghan, who was convicted of child molestation and laicized, showed that Law and his predecessor had hidden priests who had sexually abused children from police, parents and other church members. He had covered up their crimes, moving them from parish to parish, allowing them to victimize more children.

"I was impressed with him because he was both very intelligent and interested in much more than hierarchical politics."

– Dominican Fr. Thomas Doyle

The Boston Archdiocese would eventually settle about 1,000 claims of clergy sex abuse at a cost of $215 million, but by then, Law had found refuge in Rome.

Writing on his blog Dec. 21, Coyne reflected: "While I knew him [Law] to be a man of faith, a kind man and a good friend, I respect that some will feel otherwise, and so I especially ask them to join me in prayer and work for the healing and renewal of our Church."

Dominican Fr. Thomas Doyle, a canon lawyer, who over 30 years has become on outspoken advocate for abuse victims, knew Law personally since the early 1980s, beginning when Doyle was on staff at the Vatican embassy in Washington, D.C. "I was impressed with him because he was both very intelligent and interested in much more than hierarchical politics," Doyle told NCR in a statement Dec. 22.

When Law was appointed to Boston, he asked Doyle to join him there as his personal canonist. "I declined even though I knew it would have been a great career move," Doyle told NCR. A friend advised him not to take that job, he said. "I took that advice, thank God."

What very few people know, Doyle said, is that Law "was very instrumental in bringing attention to the emerging clergy abuse crisis in 1984." Doyle had turned to Law for advice and help when a case of clergy sex abuse was exposed in Lafayette, Louisiana.

Doyle was a part of a three-person team, which included civil lawyer Ray Mouton and priest-psychiatrist Mike Peterson, trying to build a response to clergy abuse for the hierarchy. The three "were struggling to get the papal nuncio and the leadership of the bishops' conference to realize that what was happening in Louisiana was merely the tip of a mammoth iceberg. Bernard Law believed us and was an active supporter and advocate for what we were doing."

"When he was made archbishop of Boston," Doyle said, "I had high hopes that because of his stature he would see that the abuse issue received the attention it demanded." But the two men drifted apart as their careers took divergent courses. Law continued his climb up the ecclesial ladder. Doyle left the Vatican embassy, joined the Air Force as a chaplain and began his advocacy work for victims of clergy sex abuse.

"When I first learned of the Boston cover-up, which was a year before The Globe's revelations, I was stunned," Doyle said. "I had a hard time believing that the man I had known and trusted was behind one of the worst cover-ups in the country.

"I was even more stunned when I saw his arrogant attitude. I will never know what happened after he got to Boston. Perhaps it was the impact of his rise in the hierarchy, but whatever it was, it was tragic."

Secrets destroy

"The Boston revelations changed the course of history," Doyle said. "One of the most important results of the Globe's investigations and their publication is that it effectively removed control of the sexual abuse phenomenon from the bishops. The victims and survivors gradually realized their power and took control."

"You cannot place absolute faith and trust in any human."

– Donna B. Doucette

The victims, their advocates and concerned Catholics successfully lobbied for changes to how the hierarchy handles cases of clergy suspected of abusing minors. According to Terance McKiernan, co-director of BishopAccountability.org, it is important to acknowledge where the church has made strides, such as the Dallas Charter and Essential Norms. Also, 40-plus U.S. dioceses have published lists of credibly accused priests; while that is less than half of the nation's dioceses, it is still more than what has been released elsewhere in the world.

But it is equally important to acknowledge what the church has lost on account of this crisis.

The most obvious loss is the squandering of resources. A 2015 investigation by NCR found that up to that point, the U.S. Catholic Church had incurred just under $4 billion in costs related to the priest sex abuse crisis since 1950.

Doucette said that Law's failure resulted in a diminishing of respect for Catholic clergy all over. Lay Catholics have emerged from the crisis with a sense that "there was a sickness and it was clericalism," she said. "You cannot place absolute faith and trust in any human."

She added, "Betrayal can happen even among those we have looked to for guidance in our moral and spiritual lives."

Fr. James Connell, a founding member of Catholic Whistleblowers, called the revelations of Law's mishandling of abuse allegation in Boston "an explosion that pointed out how he and other bishops destroyed trust."

That trust, the Milwaukee priest said, remains broken today, and evidenced by Catholics who left the church in the wake of the abuse crisis, and from those still within it who wonder whom among its leadership they can believe.

"It's a very sad commentary when we are hearing from so many people [who say to us] 'we don't know who we can trust in the church anymore,' " he said.

Church historians see Law's legacy — and that of the larger sexual abuse scandal — as a massive loss of credibility in the church, resulting in an exodus from the institution and the rise in the "nones" (those with no religious affiliation), especially among younger Catholics.

"The millennials that grew up with this crime of predator priests and the cover-up don't trust the structure of the Catholic Church," said Christopher Bellitto, professor of history at Kean University in Union, New Jersey. "They may believe in Jesus, but they're not going to trust the structure of the Catholic Church to get to Jesus."

The sex abuse crisis has "left the church impoverished, and not just financially," said Thomas Rzeznik, associate professor of history at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. "It's going to take some time — a generation or more — for the church to replenish that storehouse."

"No longer are you going to have media that work to protect the image of the church or editors who are concerned about alienating Catholics by airing the church's dirty laundry."

– Thomas Rzeznik

In addition to its impact on the church and its members, the sexual abuse crisis also has affected everything from topics of church history research to the church's relationship with the media. "No longer are you going to have media that work to protect the image of the church or editors who are concerned about alienating Catholics by airing the church's dirty laundry," Rzeznik said.

The changes that did happen in the aftermath of the crisis have helped protect children, yet accountability for bishops who participated in the cover-up has been limited. "There is very little transparency, even now, and there are not clear ways to hold bishops or religious superiors accountable," said C. Colt Anderson, professor of Christian spirituality at Fordham University in New York.

This crisis of authority in the church has led to some positive change, with many lay people claiming their own power and authority as adult Catholics while also questioning and criticizing the clericalism that contributed to the scandal and cover-up.

Yet church reform has been uneven, at best, and real change to entrenched clericalism will take time, especially since some lay Catholics are invested in the more traditional institutional culture. In some cases, lay Catholics were among those who were reluctant to expose the truth about sexual abuse.

"It takes a really long time for clerical culture to change," said Anderson. "I do believe we are moving in the right direction, especially with the sense of consciousness among the laity and some reform-minded clergy."

Already, there are Catholics — such as today's college students — who were too young to be following news reports of the crisis and thus have no first-hand memory of it. "They're familiar with it, but they do not share the trauma and the immediacy of the event," Rzeznik said. "Instead, they think about the church in new ways. They want the church to engage with issues of diversity, politicization in the church and crafting a meaningful spirituality."

Doyle calls Law "an anti-hero."

"Cardinal Law has a very vital but sad role" in this chapter of church history, Doyle said. "His attempts at control and cover-up led to the 2002 tsunami, which in turn led to society's acceptance of the evil of sexual abuse."

Trust but verify

Doucette is among those who can cite reforms the church has made in the wake of Law's 2002 resignation, including widespread application of child safety measures throughout American dioceses. Voice of the Faithful has lobbied for action on sex abuse policies as well as financial transparency in American dioceses. But response has not been uniform, she said.

Pope Francis stands with his crosier as prelates pass the casket of Cardinal Bernard F. Law at the end of his funeral Mass Dec. 21 at the Altar of the Chair in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican. Cardinal Law, who resigned as archbishop of Boston in 2002 when it became clear he had knowingly transferred priests accused of sexually abusing children, died Dec. 20 in Rome at age 86. (CNS/Reuters /Max Rossi)

Many dioceses continue to hold back release of potentially damaging files about priest sex abuse. And, while exhaustive national government studies have examined the issue of sex abuse in the church in Ireland, Australia and Germany, no national study in the United States will ever be undertaken because of the American tradition of church/state separation. Catholics have had to rely on piecemeal local investigations; the full picture may never be known.

To this day, she said, "Bishops are notoriously uncomfortable in talking about errors and sins in the hierarchy."

The chief job of bishops today is to rebuild the community's trust. To do that, Connell said, the bishops must first in a meaningful way bring survivors of sexual abuse into the conversation about how to address the abuse issue.

He also suggested the need for an "internal struggle" within the body of bishops, where the newer bishops, appointed in the last decade or so, grab the reins from bishops who were in office at a time when secrecy and self-preservation were the norms.

Finally, Connell said, the laity must demand an end to clericalism — the sense of privilege and excuse from responsibility among priests and religious — given that the clergy themselves were unlikely to change on their own.

"I really think it is a major part of the problem, and it will remain until the laity throws clericalism out," he said.

As for what lessons the church hierarchy has taken from Law's resignation, Connell hesitated to say it has learned much. While he acknowledged the Dallas Charter has aided in creating a safer environment for children, he said there are questions about the U.S. bishops' adherence to its zero-tolerance policy, and the issue of accountability remains unresolved.

Case in point, he said: Law's funeral Dec. 21 in St. Peter's Basilica followed normal procedures for a cardinal residing in Rome. Pope Francis, as is customary for the funerals of cardinals who die in Rome, arrived at the end of Mass to preside over the final commendation and farewell. He read the prayers in Latin, sprinkled the cardinal's casket with holy water and blessed it with incense. But he made no remarks about the cardinal or his life.

Cardinal Angelo Sodano, as dean of the College of Cardinals, celebrated the funeral Mass. He made no mention of Law's resignation or the abuse of children. The closest he got was saying in his homily: "Unfortunately, each one of us can sometimes lack in fidelity to our mission."

Connell said that such treatment and Law's burial at St. Mary Major Church was akin to calling him a hero and contributes to the scandal Law and other bishops brought on the church.

"That is a tremendous missed opportunity on the part of Pope Francis. He had an opportunity with this funeral to make a statement that the legacy of Law includes a terrible, terrible happening," Connell said.

McKiernan said any honors that Law received Dec. 21 were an extension of the Vatican's own mishandling of the cardinal following his resignation — that despite him admitting what he called "mistakes," he received a prominent church, was placed in the Congregation for Bishops and maintained his placement in the conclave.

While some criticize that Law was never properly disciplined for his role in the abuse crisis, McKiernan noted that his resignation still stands as an exception, in that other bishops who shielded abusive priests from the public maintained their posts at the head of their dioceses.

"Many, many other bishops who did similar things during their time in office were never removed at all, or were removed in a way that did not really connect that action with the ways they had behaved during the crisis," he told NCR.

"I don't see under Pope Francis that the church is really walking the talk, and I think that that sends a very, very bad signal down the chain."

– Terance McKiernan

In that way, McKiernan said Law wasn't a scapegoat for his brother bishops but "a convenient shorthand" who came to represent something much larger than himself. "I think that people poured a lot of their indignation into his story, but I don't think that that was inappropriate."

McKiernan said that many worry that the culture in the church has changed little when it comes to the abuse issue.

The recent lapse of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, as well as the Vatican's inability to establish a bishop accountability tribunal, are signs, he said, of the long way the church has to go to get to the core of the issue. He also pointed to Francis' defense of his appointment of Chilean Bishop Juan Barros, who has been accused of covering up abuse by a fellow priest.

"I don't see under Pope Francis that the church is really walking the talk, and I think that that sends a very, very bad signal down the chain," McKiernan said.

It's important not to view Law's death as the conclusion of the clergy abuse story, but rather an opportunity to reexamine the situation and where the church is today, not only in Boston but across the country and the globe.

"We need people to really dig into this and continue to work on this because … if the church really didn't understand why it happened, the danger is it will continue to go on and on," McKiernan told NCR.

The final word

Speaking to journalists Dec. 20, O'Malley said, "This is a very difficult day for survivors and all of us in the Archdiocese of Boston and for me."

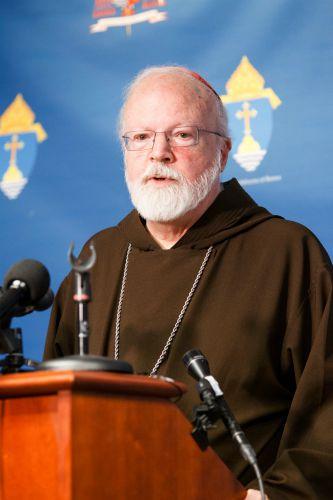

Boston Cardinal Sean O'Malley answers questions from the media on the death and legacy of Cardinal Bernard Law at the headquarters of the Archdiocese of Boston Dec. 20 in Braintree, Massachusetts. (CNS/The Pilot/Gregory L. Tracy)

"We have anticipated this day, recognizing that it would open a lot of old wounds and cause much pain and anger in those who have suffered so much already, and we share in their suffering," he continued.

The archdiocese has a continued commitment to "provide for the assistance and support for victim survivors and their families, and to strive to maintain safe environments in all of our churches, schools, institutions and agencies," O'Malley said.

For victims, the "hurt is still there, the healing is still necessary," he said. "We must all be vigilant, particularly for prevention of child abuse and to create safe environments and to be constantly monitoring how we're doing following our policies, our commitment to the whole community to take this very seriously, and do whatever we can to guarantee safe environments for our children."

Journalists asked O'Malley if he believes Law's soul will be welcomed into heaven. O'Malley replied that he doesn't know if anyone can answer that question, but added, "I hope that everyone goes to heaven."

"This is what the mission of the church is, to work so that everyone will go to heaven, but I am not here to sit in judgment of anyone," he said.

[This article was compiled and written by Dennis Coday with reporting from Heidi Schlumpf, Joshua J. McElwee, Brian Roewe, Peter Feuerherd and James Dearie. Additional material came from Catholic News Service and Religion News Service.]