Memorial plaque at the site of the former mother and baby home in Tuam, County Galway, Ireland (Courtesy of Breeda Murphy)

A proposed law to allow for the exhumation of the remains of 796 babies at a former institution for unmarried mothers in Ireland is drawing criticism from campaigners who say it doesn't go far enough.

Some 46 years have passed since two boys collecting apples in Tuam, County Galway, jumped a wall at the then-disused St. Mary's Home, and discovered a pit containing skulls and bones.

Following the January 2021 report of an official inquiry into conditions at former religious-run mother and baby homes, the Institutional Burials Bill is being debated in Ireland's Parliament and, if passed, will lead to the remains being exhumed, a DNA identification process and their reburial.

"I am not happy with it at all," said Breeda Murphy of the Tuam Mother and Baby Home Alliance. The campaigner, who helped author an alternative bill, told NCR: "There is a right way to do things and a wrong way and Government have chosen the wrong way."

Murphy is also part of the Separation, Appropriation and Loss Initiative, or SALI, which is pressing for more public involvement in the process. Among its criticisms are that the bill effectively ignores the local coroner's usual role in investigating any deaths; that the government will appoint an adjudicator and that it fails to recognize the cross-border nature of the mother and baby home issue.

Baby clothing and other items hang from a tree at a cemetery in Tuam, Ireland, where the bodies of nearly 800 infants were uncovered at the site of a former Catholic home for unmarried mothers and their children. The photo was taken Jan. 12, 2021, the day a commission investigating the treatment of women in such homes released its report. (CNS/Reuters/Clodagh Kilcoyne)

Another SALI member, Eunan Duffy, was born in 1968 to a 22-year-old unwed mother across the border in Northern Ireland. He only knew of his adoption when he needed his birth certificate to marry. Seven months later he found his still traumatized birth mother across the Irish Sea in England.

When mother and son first met 12 years ago, all she could remember of her eight months at the Good Shepherd Sisters' mother and baby home in Marianvale, Newry, was that she was given about 30 seconds to hold her son before he was taken from her.

Speaking to NCR, Duffy said it was "shocking" that the process to deal with the remains at Tuam had taken so long and that he would prefer an independent international arbiter with human rights experience, instead of a government-appointed adjudicator.

He wants all diocesan records opened to scrutiny and for families to be able to pursue inquests and criminal prosecutions.

Advertisement

The boys' gruesome find in 1975 was dismissed by police, church and local authorities as likely bones from the 1840s famine, which claimed about a million lives. At the time a priest prayed at the site, and the concrete slab the boys had dragged off was returned to cover the remains.

It took the tenacity of a local woman turned amateur historian, Catherine Corless, to discover that the remains were likely those of babies and toddlers in the care of the Congregation of the Sisters of Bon Secours, who ran the home from 1925 to 1961.

Scouring archives and the birth, marriage and death records of the Galway County Council, Corless found lists containing their names and ages and evidence that they had been baptized but never properly buried after their deaths from illnesses including measles and whooping cough.

"It's very hard to know about how the babies died," she told NCR. "Quite a lot of it adds up to neglect."

Corless unearthed a list of 798 names and ages of babies and toddlers who had reportedly died at the home and found only two were buried in the local cemetery. She vowed to track down the remaining 796 "missing babies."

Site of where archaeologist Niamh McCullagh carbon-dated samples of remains at the former mother and baby home in Tuam. (Courtesy of Breeda Murphy)

In 2016 and 2017, as part of the government's inquiry, an archaeologist, Niamh McCullagh, carbon-dated samples of remains to the time of the mother and baby home. The passage of time, environmental and other factors will likely make it impossible to identify all the remains.

In an interview for the documentary "The Missing Children," McCullagh said ideally DNA testing should have been done within six months.

After the official report about the historic conditions at the mother and baby homes was issued in January 2021, the Bon Secours sisters released a statement of "profound apologies."

"We acknowledge in particular that infants and children who died at the Home were buried in a disrespectful and unacceptable way," said the statement, signed by Sr. Eileen O'Connor.

While Corless said she was "pleased" at the proposed bill's publication on Feb. 22, she also said she feels "there should not have been a need for a bill" to deal with "something immoral and something very wrong."

A wreath laid at the site of the former mother and baby home in Tuam, seen in a picture taken December 2021 (Courtesy of Breeda Murphy)

Corless said she was disappointed it had taken so long and said she had "expected church and the religious to come on board immediately" in 2017 after the time period was verified. She believes exhumations could begin at the end of this year or early in 2023.

During her 2010 to 2012 research for an essay for the journal of the Old Tuam Historical Society, Corless' interest was piqued by the tale of the boys' discovery of "little skulls." A 1925 map marked with the word "sewerage tank" confirmed to her that the bones could not be from the famine, when the sewerage tank was still in use.

She called on the Bon Secours sisters, one of the wealthiest congregations and the largest public health care provider in Ireland to finance the operation, which is likely to cost over $14 million (13 million euro).

Peter Mulryan, chairman of the Tuam Home Survivors Network, told NCR that that he had expected what happened at the baby home to have been investigated much earlier.

"If somebody found bones at the end of my garden, human bones, straight away the whole area would be closed off," said Mulryan, adding that the police and the coroner would be called "to find out what happened."

"That's what we were denied all along," he said.

Born in 1944 at Galway Hospital to an unmarried mother who remained at St. Mary's for 12 months looking after babies and cleaning floors, Mulryan, now 77, spent four-and-a-half years at the home. He says he was neglected in the overcrowded, grey-walled institution, alongside "loads of babies crying and crying and crying."

When he left the home, he had not yet been toilet trained and his clothes were unwashed.

A photo of Peter Mulryan as a child, left, and present day; today Mulryan is chairman of the Tuam Home Survivors Network. (Courtesy of Peter Mulryan)

"Going to school was very embarrassing, nobody wanted to sit beside me because of my clothes and the hygiene. I was covered in headlice," he said. "We were nobody in society, we were always looked down upon."

He began searching for his mother at the age of 19 and finally reunited with a delicate and frail "sad-looking" woman who could not tell him much.

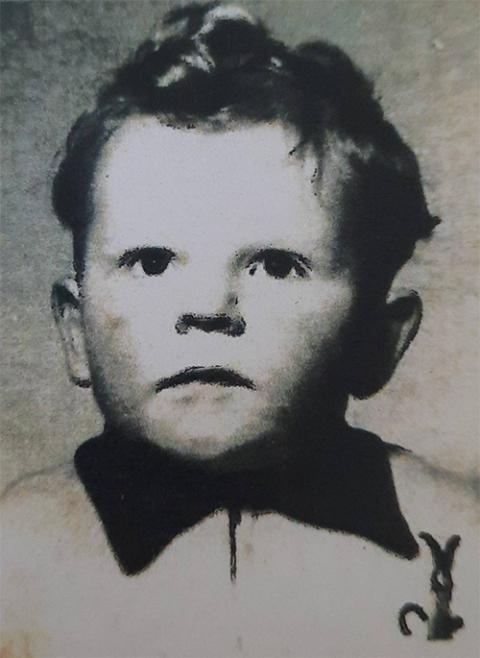

Patrick Joseph Haverty in a 1953 photo (Courtesy of Patrick Joseph Haverty)

At the age of 70 he discovered he had a sister, Marian Brigid Mulryan, who was born at the home 10 years after him. Corless' list names her as having died in 1955 aged 10 months. He still hopes it was a cover for her having been illegally adopted in America.

He fears the government will "drag out" the exhumation as long as possible. "We're all elderly and moving on and that's all they are waiting for," he said.

Patrick Joseph Haverty was fostered out of St. Mary's at the age of six-and-a-half by Teresa and Micky Hansberry. All he remembers is leaving the home hand-in-hand with his foster mother and then driving away in a car.

Haverty, 70, found out some 18 months ago that he was supposed to have been adopted earlier, in 1953, by an American couple in Rhode Island.

"I was lucky," he said now. "I suppose had I gone I'd never have met my mother."

Haverty tracked down Eileen Haverty to London, England, where he met her a couple of times and attended her funeral in 2012 and later erected a headstone on her grave.

He plans to return to the cemetery and read the nuns' apology over her grave. "So she knows she did nothing wrong," he said.

Patrick Joseph Haverty and his birth mother Eileen Haverty in 1977, the first time they met (Courtesy of Patrick Joseph Haverty)