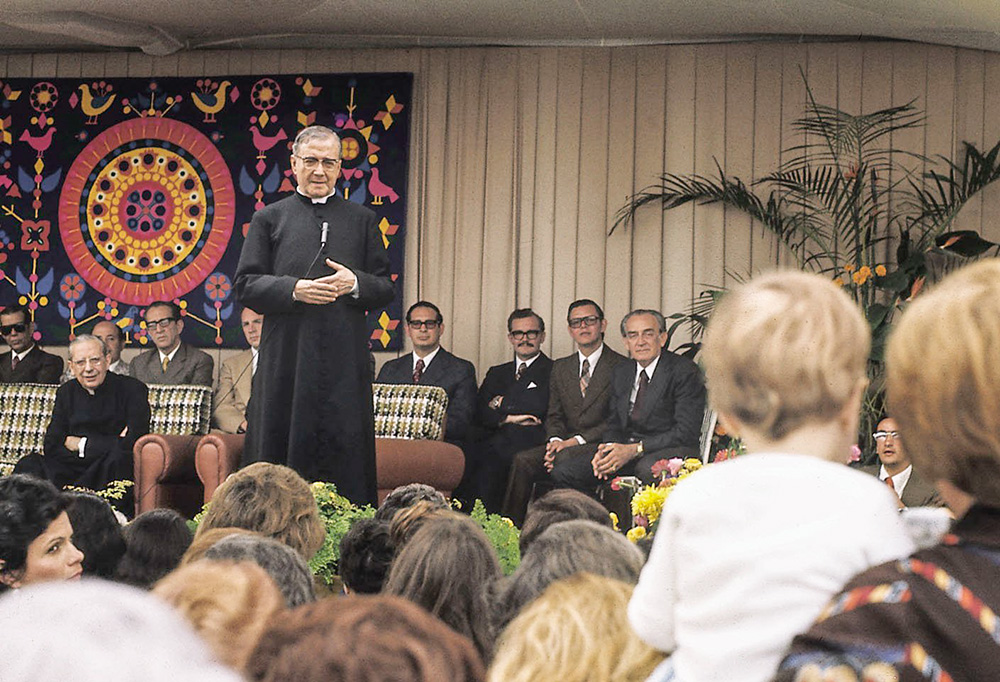

St. Josemaría Escrivá, founder of Opus Dei, in Venezuela in 1975 (CNS/Courtesy of Opus Dei)

Almost since Opus Dei was founded in 1928 in pre-Franco Spain, the conservative Catholic group has been described as a "shadowy," "secretive," "cult-like" "sect." Every few years that image, which clings to the organization like stinkweed, is reinforced in the press; as long ago as 1957, Time magazine referred to members as the "White Masons." Not for nothing did the writer Dan Brown smell the opportunity to depict a fictionalized Opus Dei as the vessel for a dangerous, cultish secret society in his bestseller The Da Vinci Code.

And of course, Opus Dei — which means "work of God" in Latin — is conservative, secretive and controversial. It has faced criticism from within the church and been embroiled in various intrachurch battles since the 1930s. Whether you view it as an insidious, ultraconservative sleeper cell or a righteous force fighting for orthodoxy in a hostile world likely reflects your own ideological priors.

Part of what makes Opus Dei unique in the church is its status as the sole personal prelature. It is not a religious order, and its ranks include both clergy and laypeople, including some of the most prominent conservative Catholics in America. Its core idea, which founder Josemaría Escrivá said was revealed to him in a vision, is the sanctification of ordinary life by laypeople living the Gospel, and its practices are rigorous and demanding.

Pope John Paul II blesses pilgrims at the end of the canonization Mass for Opus Dei founder Msgr. Josemaría Escrivá Oct. 6, 2002, outside St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican. (CNS from pool)

Because of its secrecy and reach, it has drawn scrutiny from the Vatican. Under Pope John Paul II, Opus Dei was celebrated and elevated to a prelature, with Escrivá declared a saint. Pope Francis has been warier, with the organization becoming the focus of reform efforts amid a fresh round of controversies.

Among the worst of those are allegations of human trafficking in Francis' native Argentina. Prosecutors there launched an investigation of members of the organization in September accusing them of human trafficking and slave labor. Amid persistent complaints and lawsuits are claims that Opus Dei has recruited poor young rural girls in Argentina with promises of education and a better life, only to consign them to years of hard work with no pay. It is the broadest claim ever made against the organization, which has "categorically" denied the allegations.

The judicial investigation makes Opus: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking and Right-Wing Conspiracy Inside the Catholic Church by Gareth Gore well-timed. Gore's is the latest ambitious effort to peel back the layers of Opus Dei by exploring its history, operations and influence, aiming to connect the dots from its founding, through its evolution over decades into a worldwide organization, right up to the prelature's putative prominence in a divided America.

It's a lot to pack into one narrative, and the book, while compelling in some sections, doesn't land all the punches thrown by Gore.

The best material concerns Opus Dei's influence over Spain's Banco Popular, which frames the narrative, and that may reflect the author's background as a financial journalist. According to Gore, the bank's longtime chairman, Luis Valls Taberner, had been recruited into the Work in its early days by Escrivá. Gore documents a convoluted network of shareholders and private companies, known as the Syndicate, that took over the bank and benefited for decades from favorable loans and dividends while the organization built an extensive real-estate empire.

While his writing can at times be breathless, here Gore writes with genuine insight and authority; the scale of Opus Dei's reach, and breadth of its holdings in its heyday, is remarkable.

Advertisement

The early chapters on Escrivá are more mixed. Those unfamiliar with his story will find his biography interesting. They will gain understanding of how Opus Dei grew — helped by its ties to the government of Francisco Franco — and why the organization has been controversial from its early days.

But Gore can't hide his disdain for the founder, and that brings a tone of snideness into the book. He is snarky about Escrivá's claim that the idea for Opus Dei came directly from God. In his telling, the organization grew through deception, fraud and money laundering, as well as the protection of powerful men in and out of the church.

Gore's lack of interest in spiritual matters shows in his writing and word choices, which at times have a lurid quality. Leaders of Opus Dei are frequently depicted as "plotting" and disguising their activities, preaching "truths" — the quotes are the author's — while navigating a series of "crises" that threaten to blow the lid off everything.

It is revealing that Gore writes a fair bit about Opus Dei's drive to identify "targets" for "recruitment" but very little about conversion, which, after all, is central to the church's mission. Indeed, there is virtually no space devoted to exploring the spiritual lives of Opus Dei members, especially ordinary people, or consideration of the notion that its leaders, even deeply flawed ones, might hold sincere convictions. The focus of the reporting is almost solely on the leaders and their scandals.

Undoubtedly, that approach reflects Gore's own beliefs and conclusions. But it can make the book a slog, especially in the back half, where some chapters read more like a prosecutor's brief piling up an array of evidence than an engaging narrative. Opus is not a book for the curious Catholic seeking a broad, nuanced understanding of the organization.

In its later chapters, Opus turns its focus toward the U.S. and its recent political history. While this material might feel the most relevant to Americans in 2024, and no doubt will be interesting (and maybe infuriating) to some, it often feels rehashed from other sources, and rather partisan. We read a great deal about people like Leonard Leo, the well-known conservative legal activist who has worked closely with Republicans to reshape the courts, especially with Donald Trump on his three picks to the Supreme Court.

The story of the notorious American spy and Opus Dei member Robert Hanssen is retold, including the priest who heard his confessions and kept them private. So is the saga of Fr. C. John McCloskey, the punchy U.S. representative for Opus Dei who wooed many prominent figures into the movement before being accused of sexual misconduct.

Whatever one thinks of conservative Catholics like Leo, Antonin Scalia or Bill Barr, or whether one approves of or despises conservative efforts to overturn Roe v. Wade, this is well-trod ground. Indeed, in recounting the events and activities of these figures, the author often wanders away from Opus Dei itself, only to circle back and try too hard to put the organization at the center of these political events.

In the end, Opus feels like a missed opportunity. By focusing on the most salacious and controversial parts of its history, as well as recent American politics, the book doesn't shed much new light on the lingering questions around Opus Dei or its place in the larger context of the church in the 21st century. Like so many books in this shrill and divided era, it is likely to be deeply persuasive to those already persuaded, but not many others.