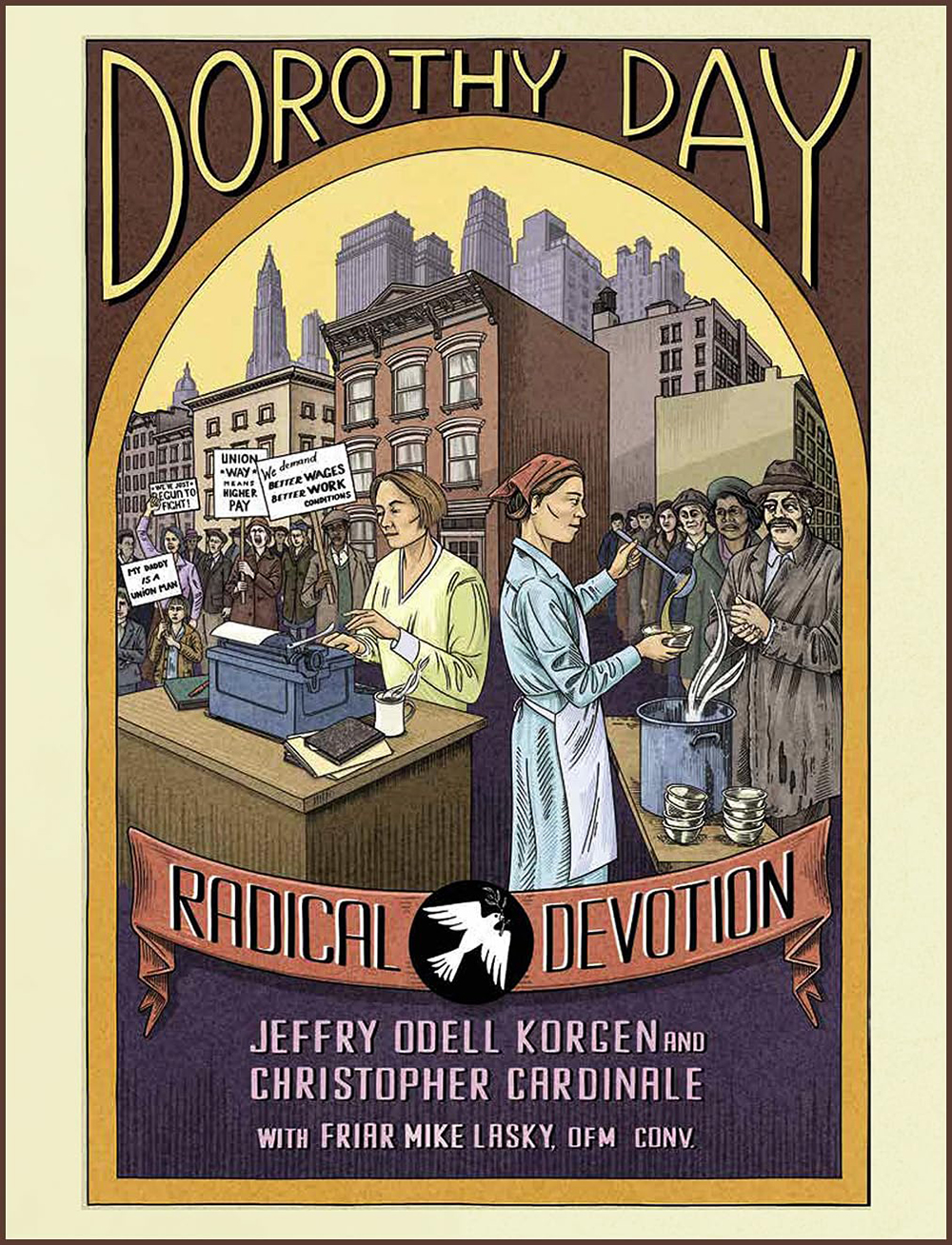

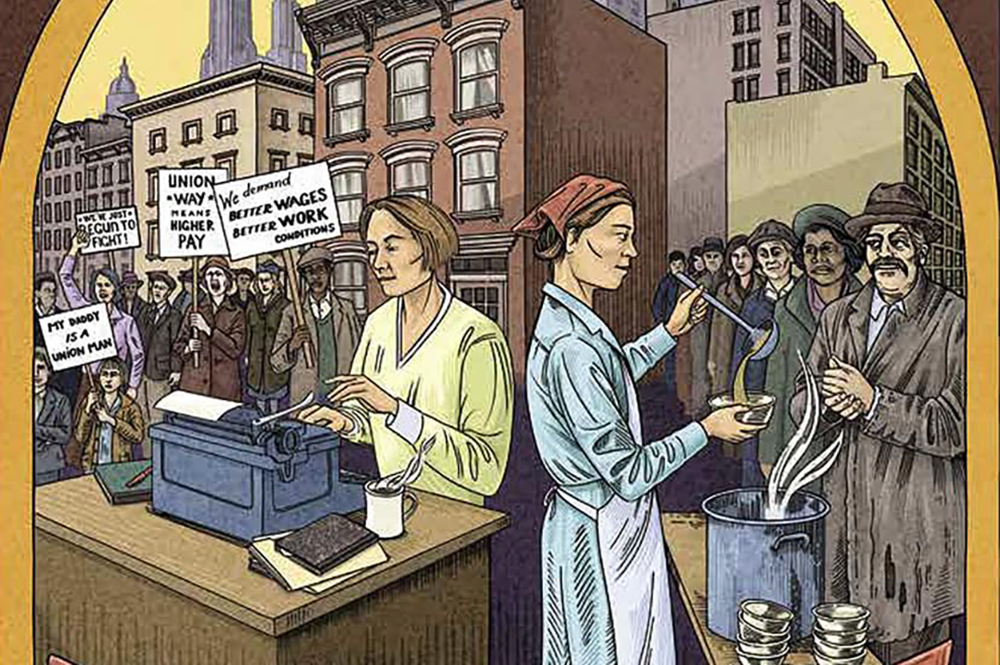

Dorothy Day: Radical Devotion is written by Jeffry Odell Korgen and illustrated by Christopher Cardinale. (Paulist Press)

Paulist Press has positioned its new graphic novel, Dorothy Day: Radical Devotion, as offering "spiritual but not religious" readers an opportunity to read Day's story in a "unique and engaging medium grounded in history — not hagiography." Call me a skeptic, but if I were a character in the pages of Radical Devotion, my own thought bubble would have read: "Oh yeah? Then why is it written by the coordinator of her canonization cause and blurbed by Cardinal Timothy Dolan?"

But my skepticism proved to be misguided.

Author Jeffry Odell Korgen does a remarkable job of fleshing out Day's life and character in such a way as to appeal to almost everyone — including those "spiritual but not religious" — while sparing no dark or ugly detail. Christopher Cardinale's layouts and art comprise the substance of Radical Devotion, lending credence to Paulist Press' pride in their choice. The graphic novel, as it turns out, is the perfect medium to convey the nuance, power and multi-dimensionality of Day's legacy.

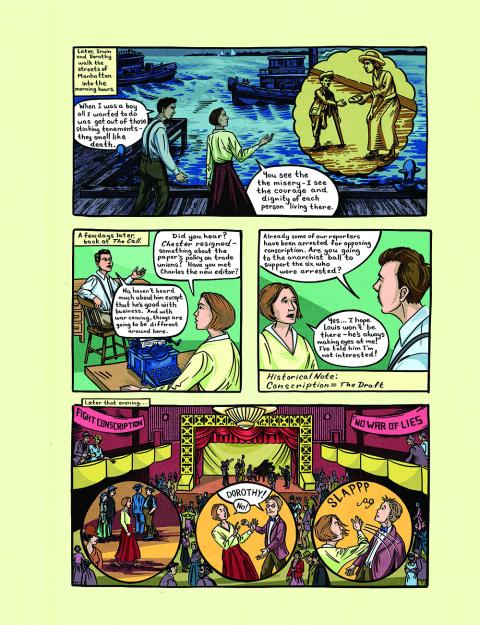

The graphic novel directly confronts — while also managing to transcend — the incessant ideological tug-of-war over Day's life, making shrewd use of its form to do things which literature or scholarship cannot.

Take the two-page spread dedicated to the contentious coffee cup Mass apocrypha: on the left of the page is the indignant, pious Dorothy, appalled and admonishing when confronted by the gross liturgical excesses of a long-haired Vatican II era priest; and on the right appears a Dorothy who, after learning of the incident, decides to order a chalice for Fr. Daniel Berrigan's future use at St. Joseph House. Printed upside down is a message asking "Which of these stories is true? Probably [the second one]. But the other story is true in the sense of communicating Dorothy's spirituality — she wanted to change the world, not the Mass." Now that's diplomacy!

More than a mere ideological balancing act, Radical Devotion is a deeply human portrayal of Day made possible by the mammoth survey of paperwork undertaken as part of her canonization cause. I learned a number of biographical details which sharpened my sense of Day as a woman in time and space following the Spirit.

I had not known that in the '50s, Day nursed Forster Batterham's longtime partner, Nanette, on her deathbed; nor that after Nanette died Forster asked Day whether she thought they could be together again — decades after their separation. According to Radical Devotion, Day later related to a religious sister that "It only took me a second to say no, but it was the longest second of my life." Another glimpse into Day's considerable personal burden is the novel's frank admission that she didn't particularly care for daughter Tamar's husband, David. In one panel, Dorothy tends to her grandchildren as David drinks himself into oblivion under a tree; her thought bubble reads: "what will become of these children?"

But the most poignant and courageous creative choice contained in Radical Devotion is its handling of Day's abortion. Having never read Day's autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin, I had only vague impressions of her early 20s — but Radical Devotion details the time she spent in the milieu of Jazz Age bohemia, including her disastrous relationship with Lionel Moise, the nature of which is rather well illuminated in this portion of a letter Day wrote in 1923 to Llewellyn Jones:

Lionel, in a fit of pique, left town with another woman a few weeks after I left, but he wrote me a letter in which he said he had gotten rid of his incubus and was going to be sober and alone all summer. That's what I came to New York for, — to get him sober and to get some writing done.

Dorothy Day: Radical Devotion stays true to its title, orienting itself to Day's eye for holiness. (Paulist Press)

After impregnating Day, Moise skipped town for Chicago, not without first urging her to abort the pregnancy. Much has been written about Dorothy's abortion: that it haunted her, that she felt herself forgiven, that having assumed herself to be sterilized she experienced the subsequent birth of Tamar as a miracle. But Radical Devotion's treatment of Day's abortion best demonstrates the work's strengths: research and vision. Nowhere else have I read that the physician who performed the abortion, Dr. Ben Reitman, was the boyfriend of writer and activist Emma Goldman.

The creative vision of the book shone in this section. While Dorothy lays on the "hobo doctor's" table, the first row of panels are black and white: these are the rows wherein Reitman asks how far along she is, and Dorothy, looking up at an I.W.W poster portraying a triumphant female personification of the worker, answers absentmindedly, "four months."

In the same row are close-ups of the tools and hands which will abort the pregnancy. But the row beneath — whose panels now radiate sepia warmth — shows Lady Labor coming down from the poster to meet Dorothy in a pose clearly inspired by the "The Creation of Adam," and embracing Dorothy, before returning to her static, two-dimensional home. Then, we return to black and white, watch Dorothy unzip her skirt, and grimace and sweat through the procedure.

Three more panels on the next page are devoted to the emotional fallout, including her two suicide attempts, but the page concludes with a panel of Dorothy smoking at her typewriter, the caption reading: "She uses her gifts to make sense of her life and pull it together — she writes an autobiographical novel The Eleventh Virgin." Lining the bottom of the panel is an excerpt from the novel: "It's impossible for a woman to take a man. She always gives, gives herself up."

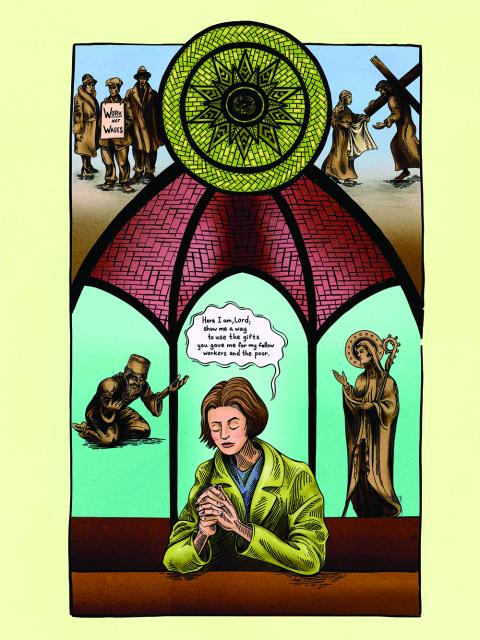

Always, Radical Devotion stays true to its title, orienting itself to Dorothy's progress, her eye for holiness — her dogged refusal to "flee" Him, as her beloved The Hound of Heaven puts it. This makes for an earnest and poignant work, though not unbuoyed by humor. For instance, during one of Dorothy's many stand-offs with the IRS, an anonymous tax worker laments to his colleague "Oh great — a martyr! Martyred by a tax bill. What are we supposed to do with that?" The colleague replies, "I miss Al Capone."

Humor also appears at the meta level, as in the epilogue, an entire page of which is dedicated to a game board layout of the canonization process. My favorite bit: "Vatican insists on single-sided copying. Recopy all evidence. Go back two spaces."

This integrated seriousness and humor seems a fitting tribute for Day, who in her wisdom always took the world much more seriously than she took herself. Most essentially, Radical Devotion offers an invaluable compendium for those who want to learn about Dorothy, warts and all, while also learning about what made her so important: her radical devotion.