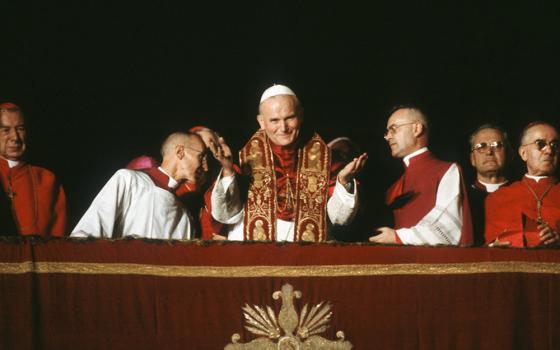

Defense Secretary Robert McNamara is shown during a news conference in Washington, D.C., April 3, 1967. One of Seymour Hersh's articles for the National Catholic Reporter, appearing in the issue dated Jan. 4, 1967, attacked the integrity and credibility of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. (AP photo)

Editor's note: To celebrate our 60th anniversary, we are republishing articles from our archives. Find more articles here. To read more about the early years of NCR, see the recently published National Catholic Reporter: Beacon of Justice, Community and Hope. You can learn more about the book at https://www.ncronline.org/

Seymour Hersh is one of the most famous investigative reporters in American history. And he wrote for the National Catholic Reporter in the 1960s.

(NCR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

In the years before Hersh's 1969 Pulitzer Prize-winning stories exposing the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, he was writing for NCR, where he had at least a half dozen bylines.

The NCR articles appeared when the young Sy Hersh was assigned to the Pentagon for The Associated Press as the war in Vietnam was escalating. Hersh caught the eye of NCR's first editor, Robert Hoyt, according to Hersh in his 2018 memoir, Reporter.

"Hoyt had reached out to me," Hersh wrote, "and offered to publish anything I wished."

Seymour Hersh, pictured in a 2009 photo (Wikimedia Commons/Flickr/Giorgio Montersino, CC BY-SA 2.0)

One of Hersh's NCR articles, stripped across the top of the NCR front page, attacked the integrity and credibility of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. It also stridently defended groundbreaking coverage by The New York Times exposing massive U.S. bombing of civilian targets in Hanoi and North Vietnam, with civilian casualties. While the stories by Harrison Salisbury turned out to be accurate, they were vehemently denied at the time by the Johnson administration.

Hersh said Hoyt "could not have picked a better time to make the pitch, because I was frantic with frustration at having to file story after story of official denials about the Salisbury dispatch — denials that I felt strongly were lies."

The story was published under a pseudonym "at the request of Bob Hoyt," Hersh wrote. Hoyt died in 2003. But Hersh also acknowledged the article angered his fellow journalists because it implicitly violated an unwritten code for the Pentagon press corps; Hersh had quoted an exchange with McNamara presumed to be off the record.

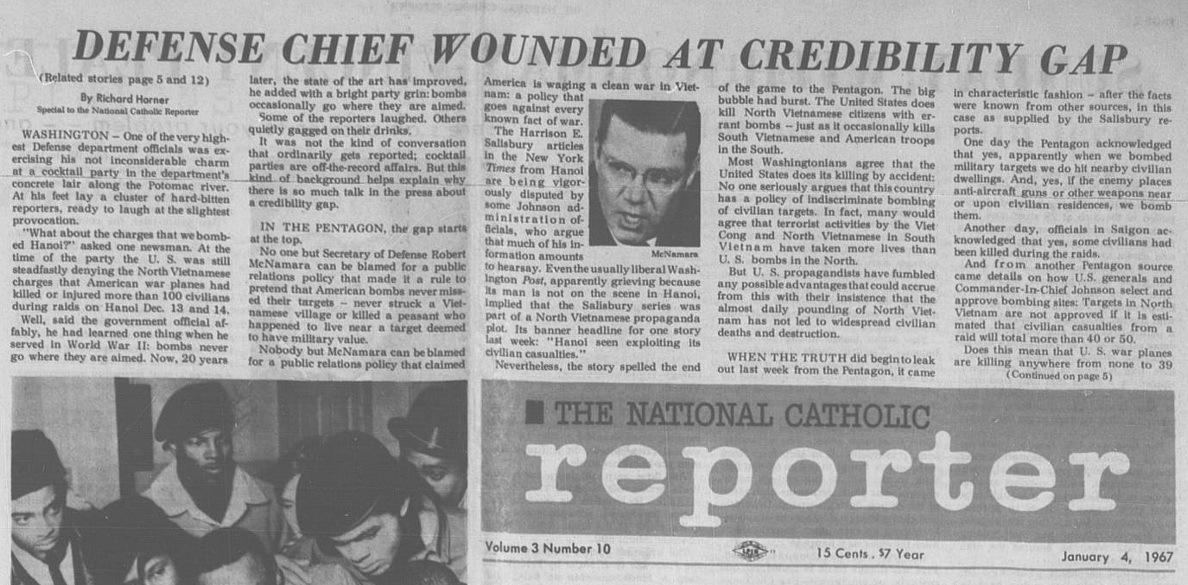

Here is Hersh's story, written under the pseudonym, Richard Horner, on Jan. 4, 1967.

DEFENSE CHIEF WOUNDED AT CREDIBILITY GAP

Jan. 4, 1967

By Richard Horner

Special to the National Catholic Reporter

WASHINGTON — One of the very highest Defense department officials was exercising his not inconsiderable charm at a cocktail party in the department's concrete lair along the Potomac river. At his feet lay a cluster of hard-bitten reporters, ready to laugh at the slightest provocation.

"What about the charges that we bombed Hanoi?" asked one newsman. At the time of the party the U. S. was still steadfastly denying the North Vietnamese charges that American war planes had killed or injured more than 100 civilians during raids on Hanoi Dec. 13 and 14.

Well, said the government official affably, he had learned one thing when he served in World War II: bombs never go where they are aimed. Now. 20 years later, the state of the art has improved, he added with a bright party grin: bombs occasionally go where they are aimed.

Some of the reporters laughed. Others quietly gagged on their drinks.

It was not the kind of conversation that ordinarily gets reported; cocktail parties are off-the-record affairs. But this kind of background helps explain why there is so much talk in the press about a credibility gap.

IN THE PENTAGON, the gap starts at the top.

No one but Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara can be blamed for a public relations policy that made it a rule to pretend that American bombs never missed their targets — never struck a Vietnamese village or killed a peasant who happened to live near a target deemed to have military value.

Nobody but McNamara can be blamed for a public relations policy that claimed America is waging a clean war in Vietnam: a policy that goes against every known fact of war.

The Harrison E. Salisbury articles in the New York Times from Hanoi are being vigorously disputed by some Johnson administration officials, who argue that much of his information amounts to hearsay. Even the usually liberal Washington Post, apparently grieving because its man is not on the scene in Hanoi, implied that the Salisbury series was part of a North Vietnamese propaganda plot. Its banner headline for one story last week: "Hanoi seen exploiting its civilian casualties."

Nevertheless, the story spelled the end of the game to the Pentagon. The big bubble had burst. The United States does kill North Vietnamese citizens with errant bombs — just as it occasionally kills South Vietnamese and American troops in the South.

Most Washingtonians agree that the United States does its killing by accident: No one seriously argues that this country has a policy of indiscriminate bombing of civilian targets. In fact, many would agree that terrorist activities by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese in South Vietnam have taken more lives than U.S. bombs in the North.

But U. S. propagandists have fumbled any possible advantages that could accrue from this with their insistence that the almost daily pounding of North Vietnam has not led to widespread civilian deaths and destruction.

Advertisement

WHEN THE TRUTH did begin to leak out last week from the Pentagon, it came in characteristic fashion -- after the facts were known from other sources, in this case as supplied by the Salisbury reports.

One day the Pentagon acknowledged that yes, apparently when we bombed military targets we do hit nearby civilian dwellings. And, yes, if the enemy places anti-aircraft guns or other weapons near or upon civilian residences, we bomb them.

Another day, officials in Saigon acknowledged that yes, some civilians had been killed during the raids.

And from another Pentagon source came details on how U.S. generals and Commander-In-Chief Johnson select and approve bombing sites: Targets in North Vietnam are not approved if it is estimated that civilian casualties from a raid will total more than 40 or 50.

Does this mean that U.S. war planes are killing anywhere from none to 39 people every time we make a strike? Another Pentagon official was asked. This junior official's reaction was a shrug, then a denial that targets are selected if the estimated civilian casualties will be under 40 or 50 — which his superior had just reported.

Seymour Hersh's article on Robert McNamara appeared on Page 1 of the Jan. 4, 1967, issue of the National Catholic Reporter. The story was published under a pseudonym. (NCR screenshot)

The reaction was typical of the Pentagon's defensive posture: nobody knows nothin'. As late as Dec. 28, in the midst of outcries over the Hanoi bombing, newsmen were given a briefing — the only one of the week — on the successful completion of a new Air Force base in Vietnam.

NEVERTHELESS, this reticence was a sharp change from the week before the Salisbury articles, when Pentagon officials were on the attack.

"You guys would rather believe Hanoi than us," one beleaguered McNamara aide told newsmen who complained about the lack of Pentagon response to the Hanoi charges.

At another point that week, a general took aside a newsman and showed him what he said were reconnaissance photographs of the two areas near Hanoi that reportedly were the main targets for the Dec. 13-14 raids.

Pointing at a series of dots, the general triumphantly announced that the photographs showed there were few homes near the targets, only some rice paddies and a few streams. But in his dispatches, Salibury describes the target areas as heavily built up and undistinguishable from similar areas inside the city.

The discrepancy is still officially unresolved.

U. S. officials no longer argue — as they did in the first heat of denials — that North Vietnam surface-to-air missiles (Sams) did all the reported damage in Hanoi.

Shortly after the furor broke, one Pentagon general privately revealed that U. S. pilots had twice seen Sams "go ballistic" — roar out of control and slam into the ground.

Two days later at a background news session with a high defense official, newsmen were told that the number of wild Sams was five. No explanation was given for the escalation.

Richard Horner is the pseudonym of a Washington newsman.