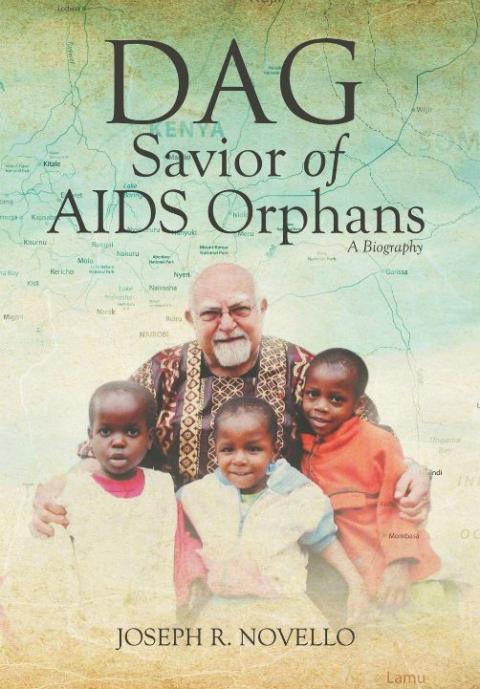

Jesuit Fr. Angelo D'Agostino, founder of Nyumbani children's home for HIV/AIDS orphans sits outside a courtroom in Nairobi, Kenya, in January 2004. He was suing the government over discriminatory practices of public schools that refused to admit many of Nyumbani's children; he won the lawsuit the following year. (Newscom/Reuters/Antony Njuguna)

Whether it's divine intervention or secular luck, I've long been blessed with the friendship of many Jesuits, beginning with those kind and generous ones where I went to school in Alabama: Spring Hill College.

For more than 30 years, I taught at Georgetown University Law Center, there to know Jesuit Fr. Robert Drinan. Teaching on the undergraduate campus, I had some time with Jesuits Richard McSorley, Horace McKenna, Leo O'Donovan and Charles Currie. I go back a bit with Jesuit Fr. William Rewak, former president of Santa Clara University and before that at Spring Hill. I had a visit one summer afternoon with Jesuit Fr. Dan Berrigan in his Upper West Side New York City apartment.

All of those Jesuits were men of passion, committed to using their gifts in varicolored forms to peacemaking.

And then there is Jesuit Fr. Angelo D'Agostino. His life story, like no other, comes to mind these days as it is found in the pages of the newly published 498-page biography, Dag: Savior of AIDS Orphans by Joseph R. Novello. In well-tempered prose laced with both facts and insights, Novello offers a portrait of a multiskilled priest who successfully twinned spirituality with dogged persistence to push ahead no matter the obstacles.

Novello is a physician with more than four decades practicing child and adolescent psychiatry in Washington. He legged through some 450 interviews with 150 people, all of whom called the Jesuit priest Dag. For Novello, it was a bonding of 31 years that began in 1975 and ending with Dag's death in 2006.

His passing, at 80, came in Nairobi, Kenya, where in 1992 he founded Nyumbani — Swahili for "home" — Africa's first orphanage for HIV-positive children, according to the biography. Three babies would be the first to be sheltered, eventually followed by hundreds.

In 1981, Pedro Arrupe, superior general of the Society of Jesus, had asked Dag to leave the comforts of Washington and base himself in Nairobi to do the work of a missionary as part of Jesuit Refugee Service.

The assignment was one of the many unexpected turns in Dag's life. In Nairobi, he saw up close a reality nowhere to be seen, much less felt, in his love-centered childhood in Providence, Rhode Island, nor in becoming a psychiatrist after going through medical school at Tufts University, nor in the 11 years up to ordination as a priest at age 40. Novello writes of Dag's thoughts on witnessing groups of children lingering near a Nairobi park:

They should be home preparing their lessons for school the next day. But here they were, looking gaunt, hungry, desperate. ... While it was true that Kenya was suffering through a rough economic period and that the average wage was probably less one dollar per day, what was going on was more than just poverty. These children were on their own. Where were their parents?

Dag "was witnessing firsthand the cruel effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Kenya's capital city."

Advertisement

Another unexpected turn had seen Dag after Tufts fall in love with a nurse but then, impatient, break the engagement because she wanted to wait a year before marrying. Another turn, or what Novello calls being "thrown for another loop," was shifting from practicing urology to surgery.

Nor would that, finally, be it. In 1954, he went to the Jesuit Manresa Retreat House in Maryland. Spiritually moved by the experience, and after a year's reflection, D'Agostino enrolled in the St. Isaac Jogues Jesuit Novitiate in Wernersville, Pennsylvania.

Having a physician in the ranks eventually led the novice master to suggest, strongly so, that Dag shift from surgery to psychiatry. He was allowed to skip his third year of studies and instead go Georgetown University Medical School to start a residency in psychiatry, which included undergoing psychoanalysis and lying on a couch five times a week while a fellow psychiatrist was taking it all in. So, asks Novello:

Did psychoanalysis change Dag? He once joked that the only real change that came of it was "I used to be a Republican and a member of the AMA; now I'm a Democrat and in the American Civil Liberties Union."

During his pre-Kenya years, Dag lived in the Jesuit community on the campus of Georgetown University. I came to know and admire him in the 1970s, and wrote a column in The Washington Post in April 1982 about him and his work in Africa. He had a thriving practice. I knew a few of his patients who shone lights on themselves at Georgetown dinner parties by telling all the chic A-listers that Father Dag was their psychoanalyst.

I'm happy to confirm that Novello has it exactly right when writing that Dag "had grown accustomed to being a free spirit. He came and went as he chose. He had a diverse set of friends all around D.C. and its suburbs. There was always someone to call, somewhere to go. His last-minute phone calls to friends for the purpose of inviting himself to dinner were becoming legendary. 'Hey this is Dag. OK if I come over to dinner?' He never got no for answer."

Off he would zip in his car with personalized license plates SJ MD. More than once, I enjoyed an evening in a home where after a parmesan fettuccine dinner, Dag would celebrate Mass in the living room or the backyard, with a slice of Italian bread as the consecrated host.

The value of Novello's research is in the revelation that Dag, driven to raise both funds and awareness for Nyumbani, knew how to game the political system of Washington. He testified in both Senate and House hearings on the AIDS epidemic.

He formed friendships with and won the support of Sen. Jesse Helms on the right and Sen. Patrick Leahy on the left, ever aware that they could pull a political string or two — or better, a rope — to get money for Nyumbani. Novello reports that along with grants from USAID, "Nyumbani and its spinoffs had grown from a rental house in downtown Nairobi to an internationally funded organization with an operating budget of close to $3 million and a staff of 130."

Novello quotes Leahy: "Whenever Dag came into my office, I'd want to hide. I knew he would want something, and I'd have to help him get it. But it was never for himself. It was for the children in Kenya. There was no refusing him."

So agreed Sen. Dennis DeConcini of Arizona: Dag "was a bulldog — and a saint."

Was that idle chatter? Really? A St. Dag? A nonprofit in Rome is now petitioning the Vatican to take the first moves to make it happen. Let's all get on the miracle watch.

[Colman McCarthy directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington. His new book is Opening Minds, Stirring Hearts: The Peace Studies Class.]

Editor's note: Sign up here to get an email alert every time Colman McCarthy's It's Happening column is posted.