Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton is pictured with Dalai Lama in 1968, whom Merton met during his Asia trip. (CNS/Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Why should anyone care about Thomas Merton today?

Merton, the famous Trappist monk and best-selling author, has now been dead for almost as long as he had lived. When he died unexpectedly on Dec. 10, 1968, at the age of 53 while in Asia on a speaking tour about the renewal of monastic life, he left behind dozens of books, thousands of journal entries, and tens of thousands of letters from correspondence with people from around the world. He also left behind a legacy, which included a model for modern Christian living that encouraged everyone — religious and lay alike — to pursue a life of prayer, holiness and social justice.

But as we consider the rapid pace of change in our contemporary context, the ever-increasing role technology plays in all aspects of our lives, and the differences too numerous to count between the life and times of a mid-20th-century monk and our own experience, it would seem at first glance that Merton's ideas, writings, vision and example belong set aside, like pieces in a museum.

They might be treated as valuable in their own right, inspiring perhaps from a distance, but not particularly relevant for us in the 21st century. Merton should be considered just another dead white male author like Dickens or Chaucer or Erasmus, to be put on a library shelf and perhaps forgotten. He can be remembered as a once important historical figure, but one not taken seriously today.

And yet I believe, upon closer examination, that Merton provides us with at least three compelling reasons for continuing to learn about him and read his work as much today as when he was living more than half a century ago.

First, there is the obvious area of continued relevance. Merton was one of the first Roman Catholic religious leaders before the Second Vatican Council to emphasize the importance of prayer and contemplation for all people and not just the religious "professionals" (i.e., nuns and priests). He articulated in his popular spiritual writing, such as Seeds of Contemplation, what Vatican II would more than a decade later describe as the "universal call to holiness." All women and men, by virtue of their baptism, have received a vocation and to discover what that is requires prayer and discernment. Each of us also has what Merton called our "true self," who we are in our fullness as known only to God. This means that to discover our truest identity requires seeking and discovering God in prayer. These insights are as timeless as the human quest for authenticity.

Second, there is the less-obvious area of the urgent timeliness of his later writings. Most readers of Merton's work are familiar with his overtly spiritual writings, but far fewer are familiar with his social criticism and writings on justice. In books with titles like Seeds of Destruction and Faith and Violence, Merton's prophetic reflections on structural racism in the United States and the relationship between fear and violence speak as challenging a message today as they did five decades ago.

Take for example his 1965 essay titled: "The Time of the End is the Time of No Room." Here Merton describes the scene of Jesus' birth in Bethlehem that eerily resonates with what is happening at the southern border of the United States today.

Into this world, this demented inn, in which there is absolutely no room for Him at all, Christ has come uninvited. But because He cannot be at home in it, because He is out of place in it, and yet He must be in it, His place is with those others for whom there is no room. His place is with those who do not belong, who are rejected by power because they are regarded as weak, those who are discredited, who are denied the status of persons, tortured, exterminated. With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in this world.

This essay, which makes for a powerful Advent and Christmas reflection, challenges Christians to link the too-often-domesticated Gospel with the signs of our time. When we look around our world, nation and local communities today, it is disturbing to recognize the systemic injustices that steadfastly persist all these decades later. It is clear that few listened to Merton then, but perhaps, just maybe, some might listen now.

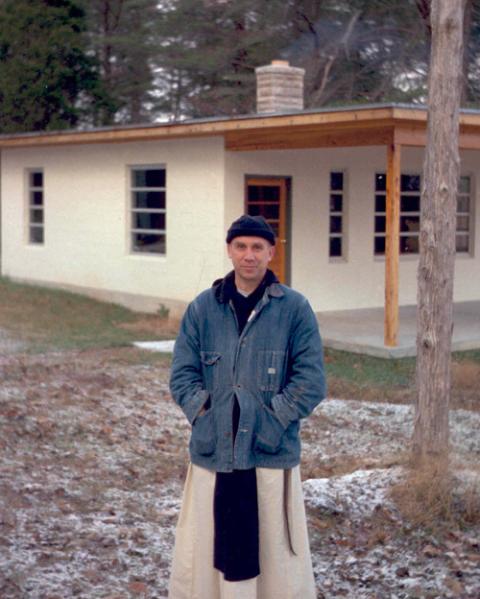

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton, pictured in an undated photo (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Third, there is what I believe is the most significant reason why people should care about Merton today: his unabashed humanity. Like his friend and contemporary, Dorothy Day, Merton is one of the few Christian exemplars we have who are not encumbered by hagiography and selective memory. A truly modern person, Merton's story is one with many turns, surprises, challenges and moments of grace. He had a life before the monastery and he had a life in the monastery: both periods lasted about 27 years. Both halves of his life reveal a complex man whose sanctity and sinfulness, pride and humility, ambition and regret are on wide display, thanks to his prolific writing practices and his willingness not to sugarcoat his joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties.

Even though most young adults today probably have not heard of Merton, his way of serving the church and world as a monk, priest and writer has tremendous potential to speak to the hunger for a more authentic, honest and transparent church, as repeatedly expressed by representative young adults in the pre-synodal meeting document in March of this year. Demographers and sociologists tell us that Millennials and members of the emergent "Generation Z" are incredulous when it comes to words without action, arguments from authority alone, and prioritization of bella figura over honestly admitting mistakes, errors and wrongdoing. They want leaders and mentors who can ask for forgiveness when needed and offer forgiveness when asked.

Young people — and not-so-young people alike — want "real" Christian models, women and men who inspire us not by their perfection in life and faith, but by their committed struggle in life to keep the faith. Day's experience of ongoing conversion and struggles for peace and justice on behalf of the poor, and Mother Teresa's long trial of experiencing God's absence while nevertheless persisting in caring for society's "untouchables" — these are Christians that speak to women and men today. It is their humanity on display that makes them both holy and relevant.

Merton is another such model.

We should care about Thomas Merton today because in many ways he reveals something to us about who we are: modern women and men, religious and laity, striving to connect the faith of Christianity with the particularity of our lives.

His wrestling with religious censors who sought to mitigate or silence his publishing about violence, racism and the Christian responsibility to put faith into action speaks to experiences of those whose consciences call for more than banal Christian platitudes, and take the risk to work for justice in the church and world.

His ongoing struggle with ego and ambition while also sincerely desiring a more simple, prayerful and eremitical life speaks to the conflicted motivations we all face in decision-making.

Advertisement

His falling in love with a nurse at the age of 50, the genuine affection they had for one another, and the turmoil recorded in his journals and poetry about his discernment — and his ultimate decision to remain a monk — speak to the universal human condition of love and loss, which monks and nuns and laity all experience, if in different ways and at different times.

We should care about Thomas Merton today because in many ways he reveals something to us about who we are: modern women and men, religious and laity, striving to connect the faith of Christianity with the particularity of our lives. Fifty years after his death, Merton not only intercedes for us from within that great cloud of witnesses that has gone before, but he has left us the story of his life and the text of his many writings to guide us on our own journey.

[Franciscan Fr. Daniel P. Horan is a Franciscan friar of Holy Name Province, assistant professor of systematic theology and spirituality at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, and the author of 12 books, including The Franciscan Heart of Thomas Merton: A New Look at the Spiritual Inspiration of His Life, Thought, and Writing.]