Altar server Angelo Alcasabas prepares the altar during an annual "Pre-Pride Festive Mass" at St. Francis of Assisi Church in New York City on June 29, 2019. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Research shows that one of the most dramatic changes in American Catholic attitudes over the last few decades has been the shift with respect to the acceptance of LGBTQ+ people, their relationships, and their decisions to marry and form families.

In our book Catholicism at a Crossroads: The Present and Future of America's Largest Church, my co-authors and I draw on data from the six waves of our survey conducted between 1987 and 2017 that document this dramatic shift in attitudes. We also discuss how it is reflective of changes in the larger society — in both family structure and attitudes toward sexuality — as well as in the church's approach to its pastoral mission.

One way we examined Catholics' attitudes about sexuality and marriage was through a series of questions on our survey that asked what is entailed in being a "good Catholic." Specifically, respondents were asked if they think a person can be a good Catholic without heeding the church hierarchy's opposition to same-sex relationships or without their marriage being approved by the Catholic Church, which in the recent wave of the survey would include same-sex civil marriages.

Compared to 1987, more Catholics today believe they can be a good Catholic without obeying the church's teaching with respect to same-sex relationships (55% in 1987 and 73% in 2017). And compared to 1993, more believe they can be a good Catholic without their marriage being approved by the church (61% in 1993 and 77% in 2017).

Catholics today are also more likely to believe that moral authority regarding these issues rests with the individual rather than with church leaders. (This issue of moral authority is addressed in greater detail in the article written by my co-author Paul Perl.)

For instance, when asked "who should have final say on the morality" of "a Catholic who engages in same-sex relations — church leaders, individuals, or both?", only 39% of Catholics said "individuals" at the time of our first survey in 1987, compared to a majority (58%) of Catholics in our most recent survey. While 32% of Catholics in 1987 said church leaders alone should have final say on the morality of a Catholic who engages in same-sex relations, only 13% of Catholics in 2017 said the same.

These data present clear evidence of Catholics' increasing reliance on their own lived experiences and individual consciences in making these moral decisions. They are more likely today than in the past to recognize their own lived experience as a source for understanding God's will in their lives.

This dramatic shift in attitudes among Catholics is especially evident when Catholics are asked directly about the morality of same-sex relationships and their support for legal same-sex marriage. Using data from a variety of polls, we show in our book that the percentage of American Catholics who say that same-sex relationships are always wrong fell most dramatically in the early 1990s, from 72% in 1991 to 47% in 1996. As of 2018, only 21% of American Catholics regarded same-sex relationships as always wrong.

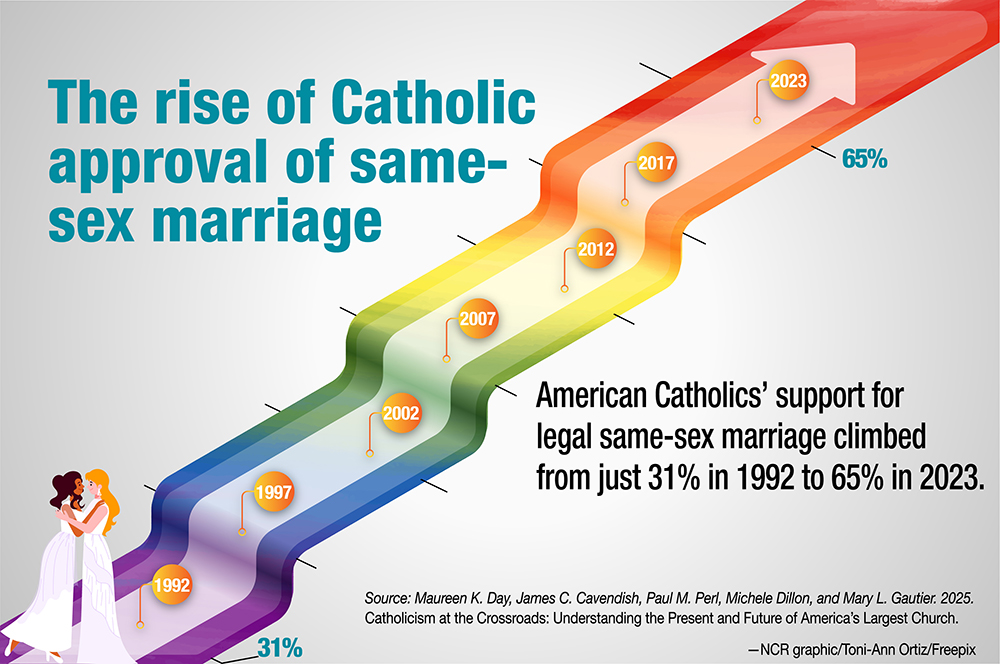

Over the same time period, American Catholics' support for legal same-sex marriage climbed from just 31% in 1992 to 65% in 2023.

These trends mark a watershed in Catholic attitudes toward LGBTQ+ issues. They also indicate that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' advocacy against civil same-sex marriage, both before and after the Obergefell v. Hodges decision in 2015, is out of step with the beliefs of the majority of American Catholics.

We interpret this shift in attitudes as reflective of changes in the larger society. Since 1987, when the first survey in our series was conducted, the complexion of American families has changed significantly. More Americans today are delaying or forgoing marriage, and more are choosing to cohabit rather than marry.

Advertisement

At the same time, more LGBTQ+ Americans are choosing to get married civilly and raise children. Based on the 2020 Census and Current Population Surveys, the U.S. Census Bureau has reported increases in the percentages of blended families, of interracial and same-sex marriages, and of same-sex couples (as many as 15% of all such couples) who have a child under 18 in their household. Also, increasing numbers of Americans are likely to know someone personally — a close friend or family member — who is gay or lesbian.

In keeping pace with these changes, Pope Francis has advocated for a more welcoming, pastoral approach to the LGBTQ+ population, an approach that calls upon pastoral ministers — indeed, on all Catholics — to encounter, listen to and accompany individuals whose lives may not resemble the church's traditional ideals. Without changing the church's formal doctrines with respect to marriage and sexuality, the pope has invited church ministers to meet Catholics where they are, and to respect their consciences and lived experiences.

In Amoris Laetitia ("The Joy of Love"), Francis explicitly acknowledged and affirmed the "great variety of family situations that can offer a certain stability," including the support that same-sex partners can provide to one another, even though such unions "may not simply be equated with marriage."

Catholics are more likely today than in the past to recognize their own lived experience as a source for understanding God's will in their lives.

Francis has affirmed the rights of LGBTQ+ people to receive the sacraments, be baptized, and serve as godparents. In December 2023, the Vatican approved the blessing of same-sex couples in certain circumstances.

Some of the church leaders we interviewed for our book acknowledge the tension in trying to strike a balance between the church's traditional teachings with respect to marriage and sexuality and Francis' call for a more welcoming, inclusive Catholicism that encounters, listens to and accompanies LGBTQ+ people on their journey. They recognize that such tensions are inevitable whenever the church's doctrinal teachings are put in conversation with changing secular realities, with social scientific findings about people's lived realities and with secular notions of justice and rights.

How, for instance, does one reconcile the church's teaching that marriage is reserved for a union between one man and one women with social scientific research findings showing the social benefits of civil same-sex marriage and the fact that a large majority of Americans believe that the legalization of same-sex marriage is good thing for society?

Some church leaders we interviewed are longing for models to engage this conversation in ways that reduce tension felt by pastoral ministers while satisfying the pastoral needs of the church. We hope that our research and the insights of the leaders we spoke with will contribute in meaningful ways to this conversation.