Catholics attend Mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City in 2018. (Dreamstime/Bumbleedee)

A century ago, surges in Catholic immigrants from Europe raised fear among native-born Protestants that the newcomers were beholden to the dictates of the pope in Rome — that they would fail to accept American norms, ideals and practices. The nativists need not have been so worried. American Catholics eventually proved quite independent in their thinking. In particular, they have, for quite some time now, preferred to decide for themselves on many questions of morality.

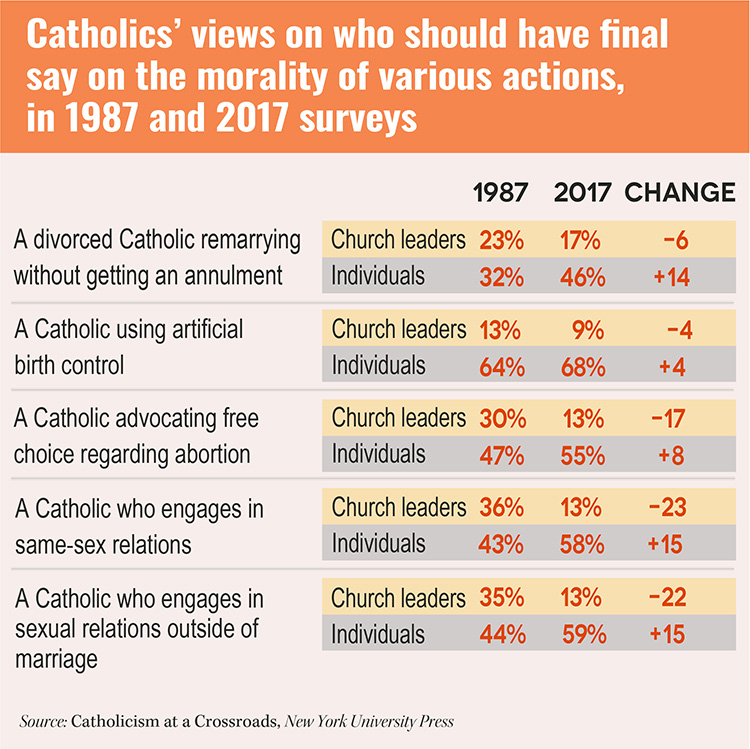

The American Catholic Laity Surveys are a series of surveys that have been conducted every six years from 1987 to 2017; the latest findings were published in book format just this month. Each asked respondents who they thought should have the final say in deciding the morality of five different issues.

There were three possible responses: "church leaders such as the pope and bishops," "individuals taking Church teachings into account and deciding for themselves" and "both individuals and leaders working together." The following graphic shows results from the first and last surveys.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Catholics were already independently minded in 1987. For any given item in this series, fewer than 40% said that church leaders should have the final say in determining morality. In each case, the percentage stating that individuals should make the final say was larger.

By 2017, fewer than 20% said that church leaders should have the final say on any given item in the series. Changes have been largest for sexual relations outside of marriage and for same-sex sexual relations. The latter shift coincides with growing acceptance among Catholics for same-sex relationships and gay marriage.

Many sociologists view birth control as a key factor in driving Catholics' moral individualism. A survey in 1953 showed that about 60% of Catholics agreed with the church's prohibition of artificial contraception.

But this support proved fragile. It fell to about 50% a decade later. Why? The limited survey data available suggest that Catholics increasingly believed that pleasure, in and of itself and independent of conception, is a legitimate purpose of sex in marriage.

Anticipation of official change rose in 1964 when Pope Paul VI announced that the issue of birth control was being studied by a Vatican commission. The commission concluded with a report for the pope recommending that he allow all forms of "artificial" contraception; that report was not supposed to be widely released, but it was leaked to the National Catholic Reporter and its findings made public.

Advertisement

Ultimately, the pope decided against making any changes to church teaching. But it was too late, at least for U.S. Catholics. They had already decided this was a personal matter. By the early 1970s, fewer than 20% agreed with the birth control teaching. The table above reflects this fact; already in 1987 nearly two-thirds of Catholics said final say on the issue should rest with individuals.

Though the 1960s controversy over contraception has received the most attention, we should not ignore two concurrent changes in Catholics' moral attitudes. At roughly the same time, Catholics became more accepting of remarriage after divorce and of abortion in the so-called "hard" cases — rape or incest, health of the mother and deformity in the child.

These attitudinal shifts brought Catholics closer in line with the more accepting positions already held by a majority of the general public, but this change seems unrelated to the women's rights movement or societal norms associated with the "sexual revolution"; it preceded both. This revolution was internal to Catholicism.

Hypothetically, Catholics' willingness to defer to church teaching might depend on whether they perceive their leaders as speaking with a special religious authority. Data indicates that there is no apparent upward or downward trend over time. The results range from about one-third to one-half, with a median of 40%.

Perhaps surprisingly, there is no evident impact of the sexual abuse scandal, which broke on a widespread scale in 2002. In fact, after poring over a great deal of data, we could find no clear evidence of the scandal producing a long-term impact on Catholics' willingness to defer to church teaching or their recognition of the moral authority of church leaders.

This stands in contrast to what most leaders we interviewed believe. Whether leaning more to the "left" or "right," they were virtually unanimous in perceiving Catholics as being less likely to listen to the church due to the scandal. We suggest another way of looking at this: The scandal provided some Catholics with an easy rationalization for what they were already doing — making up their own minds.