(NCR photo/Teresa Malcolm)

"Forgive us our trespasses: grant us your peace" is Pope Francis' theme for the World Day of Peace, today, Jan. 1, 2025. His plea is for a year blessed by forgiveness — forgiveness between nations, forgiveness between individuals. His appeal is a challenge and an opportunity not just to give and receive forgiveness, but to better understand what forgiveness is — and what it is not.

His timing couldn't have been better, since forgiveness is increasingly questioned as a therapeutic goal and a Christian aspiration. In 2023, Presidential Medal of Freedom awardee Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries, won awards for his compellingly titled book Forgive Everyone Everything. At the same time, other voices have begged to differ. Forgiveness isn't meant for everyone, they insist, and not everything can or should be forgiven.

One such voice is author and therapist Amanda Gregory. She asserts that while forgiveness is helpful for some, it isn't necessary for everyone — especially trauma victims like herself. When quoted in The New York Times about her forthcoming book, You Don't Need to Forgive: Trauma Recovery on Your Own Terms, Gregory challenges what she says is a widespread assumption that forgiveness is essential for psychological healing. That view is glibly proliferated, the article notes, through TED Talks and self-help books.

Gregory's conclusions are echoed by Catholic journalist Kaya Oakes. In Not So Sorry: Abusers, False Apologies, and the Limits of Forgiveness, Oakes also considers the experiences of trauma victims, including survivors of clergy sexual abuse. She takes particular aim at the demands of forgiveness made by those in power that protect perpetrators and institutions at the expense of the injured.

In the wake of severe wrongdoing, Oakes concludes, forgiveness "is not always possible."

Oakes longs for a "more forgiving definition of forgiveness." In light of society's growing trauma awareness and appreciation of how forgiveness can be misunderstood and even weaponized, Oakes makes a compelling request.

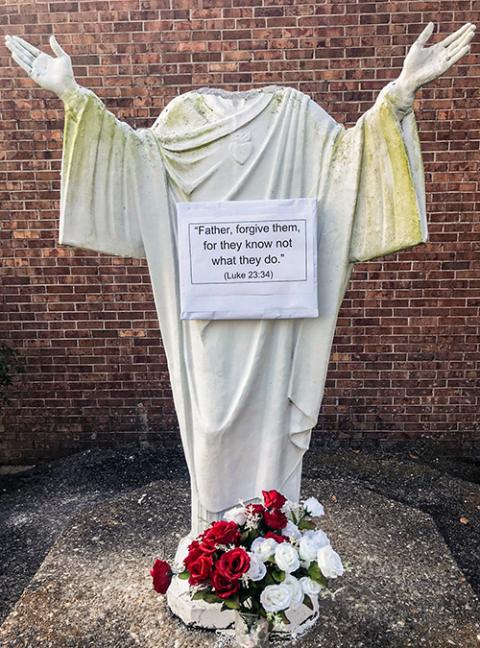

Following vandalism to a statue of Jesus during the overnight hours of Sept. 12-13, 2023, parishioners at Holy Savior Parish in Lockport, La., left a message of forgiveness for the unknown perpetrator, invoking Jesus' words from Luke 23:34. (OSV News/Holy Savior Parish/James Rome)

However, her conclusion that forgiveness has limits, and Gregory's conjecture that forgiveness is merely an option, are difficult to reconcile with a Christian worldview, grounded in the very words and actions of Jesus himself.

That being said, what Jesus meant by forgiveness isn't always clear. His words from the cross — "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do" — are often understood that if Jesus could forgive his executioners, there's nothing his followers cannot and should not forgive either.

Yet Oakes points out that what Jesus forgave here was an act of ignorance — and ignorance is easier to forgive than pure malice. She asks: Must we forgive those who knew exactly what they were doing?

In Matthew's Gospel, Jesus tells of a "wicked" servant tortured for his unforgivingness. "So will my heavenly Father do to you," he warns, "unless each of you forgives his brother from his heart."

Elsewhere, Jesus promises those who won't forgive that "neither will your Father forgive your transgressions." That immediately followed his introduction of what became the Our Father: "Forgive us our trespasses," the prayer pleads, but only "as we forgive those who trespass against us."

All this suggests that, for Christians, forgiving others is nonnegotiable — and not just those who acted in ignorance.

At the same time, Jesus' words have been used to cudgel vulnerable and hurting people into offering a forced, premature, guilt-laden and fear-driven facsimile of forgiveness. Sometimes Jesus' words are brandished in a confused but sincere effort to honor God's will. At worst, they're wielded to silence a victim or protect a perpetrator's or an institution's reputation.

One such experience led attorney and author Rachael Denhollander to conclude that "the church is one of the worst places to go for help." She was among the more than 200 gymnasts sexually assaulted by Larry Nassar — the notorious physician and Catholic eucharistic minister now jailed for life. The evangelical pastors Denhollander consulted insisted that immediate forgiveness of Nassar was required by her faith and would flood her with peace. They had no appreciation of the deep trauma she'd suffered.

Former gymnast Rachael Denhollander, center, is hugged after giving her victim impact statement during the seventh day of Larry Nassar's sentencing hearing Jan. 24, 2018, in Lansing, Mich. (AP/Carlos Osorio)

Her experience is not unique to evangelical circles. Merianna Harrelson, a mainline Protestant minister of the United Church of Christ, painfully recalls multiple stories of sexual assault victims "forced to sit in the same room as the person who violated them and forgive them in front of a third party" — a practice she rightly labels as "spiritual abuse."

In the Catholic world, forgiveness demands have been imposed upon victims of clergy sexual misconduct. Survivors of domestic violence speak of priests insisting that they forgive and reconcile with battering spouses — imposing religious guilt, prolonging relationships that should end, perpetuating the abuse cycle of harm followed by "forgiveness," and even endangering lives.

Is this really what Jesus envisioned when he spoke of forgiveness? If not, then what did he mean? Oakes conjectures that his understanding of forgiveness, given his Jewishness, would have presumed repentance and atonement on an offender's part. Yet this overlooks how Jesus challenged the conventional Jewish thinking of his time. He rejected "eye for an eye" retribution and insisted upon loving one's enemies.

Love for one's enemies would seem to include forgiving any and all of them. But to Oakes, this is harmful "fundamentalist" thinking that rubs salt in open wounds and "fetishizes" forgiveness. Christian insistence that everyone and everything should be forgiven, she contends in The Revealer, is enmeshed with America's history of "manifest destiny, slavery, colonialism, misogyny, homophobia, and many other social ills." Is she right?

Advertisement

Social ills can indeed corrupt an understanding of forgiveness and lead to its misuse. In Caste: The Origin of Our Discontents, Pulitzer Prize winner Isabel Wilkerson contends that public forgiveness of whites by Blacks, while sometimes an "abiding expression of faith," is also a culturally conditioned survival mechanism.

For "people at the margins," she writes, extending "forgiveness" is sometimes a necessary submissive act to stay safe, or even stay alive.

In her Harper's Bazaar essay "How Forgiveness Has Been Weaponized Against Women," Megan Feldman Bettencourt observes that, in allegations of sexual abuse, there may be greater cultural sympathy for accused men as opposed to accusing women — a misogyny labeled "himpathy." This bias has led some women to conclude they must choose between offering forgiveness or pursuing justice — a dichotomy Feldman Bettencourt calls a "toxic brew of nonsense."

That is toxic nonsense. Forgiveness can be offered while pursuing justice, as Denhollander did while testifying against Nassar in a court of law. As Pope Francis explains in Fratelli Tutti, "Forgiveness is precisely what enables us to pursue justice without falling into a spiral of revenge or the injustice of forgetting."

Yet a fear that forgiveness can let a perpetrator "off the hook" — a common misconception highlighted by Oakes — has contributed to the pushback against "forgiveness culture."

Equating forgiveness with reconciliation is another common misconception. "Repentance and reconciliation," says Oakes, "have to come first." But that puts the cart before the horse.

While forgiveness is a step in healing broken relationships, forgiveness need not lead to reconciliation. Reconciliation involves two parties; forgiveness requires only one. Forgiveness and self-protection are not mutually exclusive. We can forgive from a distance those we should keep at a distance.

The covers of Amanda Gregory's book You Don't Need to Forgive: Trauma Recovery on Your Own Terms, and Kaya Oakes' book Not So Sorry: Abusers, False Apologies, and the Limits of Forgiveness

Oakes further insists that it's acceptable to be a "moral unforgiver" and that the remorseless aren't "owed forgiveness." Yet this is hard to square with Jesus' teaching that his followers should forgive an offender "seventy-seven times" (Matthew 18:22).

And if such forgiveness is an expression of unconditional Christian love, then forgiveness is unconditional, too. Reconciliation might be earned through rebuilt trust. But forgiveness, like love, is neither earned nor owned. It is a free gift.

"If forgiveness is gratuitous," Francis explains, "then it can be shown even to someone who resists repentance."

Forgiveness language can be "sloppy and lazy," Oakes concedes — including her own. Popular conceptions of forgiveness can be broad and imprecise, leading to confusion and misapplication.

That's why forgiveness science pioneer Robert Enright of the University of Wisconsin, himself a Catholic, cautions in Psychology Today against "false notions" of forgiveness. He challenges Gregory's assertions and those like Oakes who claim that forgiveness has become a "fetish." "Do not believe," Enright concludes, "everything you read with the word 'forgiveness' in it."

Then what should we believe about forgiveness? Is it a dangerous concept imposed by religious zealots or inexperienced counselors? Just another faddish self-help technique that's withering under scrutiny? Merely a therapeutic option for wounded persons whose other coping methods aren't working?

Both Gregory and Oakes stress that they're not anti-forgiveness; they just don't want it crammed down people's throats. And Enright agrees: "Forgiveness never ever should be forced onto anyone."

So where does this leave the hurting Christian? Can understanding forgiveness as a choice be reconciled with Jesus' teaching?

A woman reacts while leaving a Mass at the Bilbao Cathedral in Spain, March 24, 2023, where forgiveness was asked from victims of sexual abuse within the Catholic Church. The Mass was concelebrated by Bishop Joseba Segura of Bilbao, and Fr. Josu Lopez Villalba, a victim of sexual abuse. (OSV News/Reuters/Vincent West)

Oblate Fr. Ronald Rolheiser writes that those "who cannot forgive others" exclude themselves from heaven's banquet, which is "only open to everyone who is willing to sit down with everyone." But is that fair to expect of abuse victims?

Can a Christian, as Oakes says, be a "moral unforgiver?" In Fratelli Tutti, even Francis concedes that it's "humanly understandable" when people "cannot" forgive grave injustice and cruelty.

Yet Francis' concession to what's "humanly understandable" may hint at the beginnings of a compassionate, trauma-informed, Christian understanding of forgiveness. Because for a Christian, forgiveness is not only a human act; it's also a cooperation with grace. And while it may lead to a process of therapeutic healing, there's a distinction between choosing to forgive as an expression of discipleship, and choosing to begin the hard work of healing from deep wounds. "Decisional forgiveness" can become "emotional forgiveness." But they're not the same.

Might there then be a way to "forgive everyone everything" while acknowledging criticisms raised by Gregory, Oakes and others? Is there an approach to forgiveness that honors human agency, requires neither apologies nor reconciliation, needn't be earned or deserved, and isn't a "get out of jail free" card or a concession to undue pressure or social maladies? Can there be a definition that isn't "fundamentalist," truly acknowledges a wounded person's pain, and accepts that forgiveness is a process that takes a long time — maybe even a lifetime?

"In the face of an action that can never be tolerated, justified, or excused, we can still forgive," Francis assures us in Fratelli Tutti. But where would such a process start? When imagining forgiveness, Rolheiser's heavenly banquet often comes first to mind.

Yet that's the end point of an arduous journey that begins with a single step: a choice, even when consumed by rage and pain, to not retaliate and seek revenge. Coupled with that, we can pray. Even if all we can muster is: "Help me not be consumed with hate. Help me not take an eye for an eye."

And then, we can let God's grace, God's mercy and God's patience, take things from there.