President Donald Trump in the Diplomatic Room of the White House in Washington Oct. 13 (CNS/Reuters/Kevin Lamarque)

Next week marks the first anniversary of the election of Donald Trump as the president of the United States. In one sense, we have learned very little about the man in the past year. He governs as he campaigned: mercurial, thin-skinned, populist, ill-informed, disdainful of democratic traditions and norms, narcissistic. This is who he is and none of us should be surprised.

But, in another sense, we all have learned important things in the past year, things about ourselves and our country, as we have watched our political system bend in the strong winds of the Trump presidency. In the next few columns, I will look at what we have learned and today, I begin by asking: What have the Republicans learned?

The most basic fact the Republicans learned is that their base is not united around a core set of principles, but that it can be animated by a core set of resentments, resentments that are dripping in the tropes of white nationalism.

"It is clear at this moment that a traditional conservative who believes in limited government and free markets, who is devoted to free trade, and who is pro-immigration, has a narrower and narrower path to nomination in the Republican party — the party that for so long has defined itself by belief in those things," said Sen. Jeff Flake in a speech on the Senate floor announcing he was not running for re-election.

The lack of any shared underlying philosophic beliefs was made evident by the effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Every attempt by Senate leaders to appease the hardcore conservative members of their caucus meant that they lost one of the more moderate members of their caucus, and vice versa. They may have been united in their opposition to the Affordable Care Act and they had certainly all campaigned on repealing and replacing it for years, but it turns out that they disliked the dreaded law for different reasons, and sought different ways of fixing its shortcomings. The reasons that Sen. Ted Cruz and Sen. Susan Collins run as Republicans turn out to be vastly different.

The president is not known for his ideological commitments one way or the other. He campaigned as a businessman and a dealmaker, someone who could fix what was wrong with Washington the way a mechanic fixes what is wrong with your car. He could persuade, entice, seal the deal, he promised.

He did not realize, and the American people did not care, that politics is not an automobile, that its normal conduct of business consists in aligning ideas and policies with realities, political and otherwise, that the skills needed to ink a real estate development might be different from those needed to build a governing coalition.

In the event, he also bragged that his smarts were enough, and, again, the American people were insufficiently suspicious of the fact that this man was utterly ignorant of large and consequential facts, to say nothing of nuances, regarding public policy. History makes no claims on Trump's brain. It was like turning to a successful baseball coach to take over the Dallas Cowboys, or hiring an electrician to do your plumbing.

Trump, however, did not run merely as a dealmaker. He ran as someone willing to traffic in the dark underside of American populism. Previous Republicans were willing to wink at white nationalism, but Trump was willing to do more than wink.

I want to believe that previous Republican candidates complained about political correctness because they found it annoying, an example of elite academics trying to make the rest of us conform to their theories. It always struck me as an odd complaint for a politician to level, because most voters do not find themselves at a cocktail party with a boring Upper West Side professor complaining about Columbus Day, nor do they read the kind of ridiculous academic jargon that allows professors to mistake themselves for hip social activists.

Trump understood that the complaint against political correctness resonated with working-class voters for the worst of reasons, that the focus on racial and sexual minorities and women at the heart of political correctness was a source of deep resentment for many white Americans whose luck had turned south and few liberals ever cared about them. Instead of seeking a hopeful and inclusive vision as Ronald Reagan used to do, Trump has governed as he campaigned, on a dystopian and divisive mantra. Remember "American carnage"?

Advertisement

Whenever the president gets into a rough patch, he stokes this racial animus that had been coddled for too long. Whenever he gets fed up with Washington, he goes on the road so he can whip up a rally with chants of "Build the wall!" Whenever he gets a chance to get into verbal fisticuffs with a black or Latino member of Congress, he takes it.

All the many "gaffes" this man has made were not gaffes at all. When he attacked the Khans during the campaign, he did not see the parents of a soldier killed in action defending the United States. He saw two Muslims. And attacking two Muslims is good politics for Trump and, consequently, for today's Republican Party.

Flake's decision to not seek re-election is related to Trump but more is at work. Trump has changed the focus of the Republican Party and he owns the base Flake would need to win. Trump is not merely a symptom of what is wrong with the GOP. A latent, ugly populism was there all along. Trump has ignited it, made it visible and powerful, powerful enough to cause a sitting senator to decline a re-election bid.

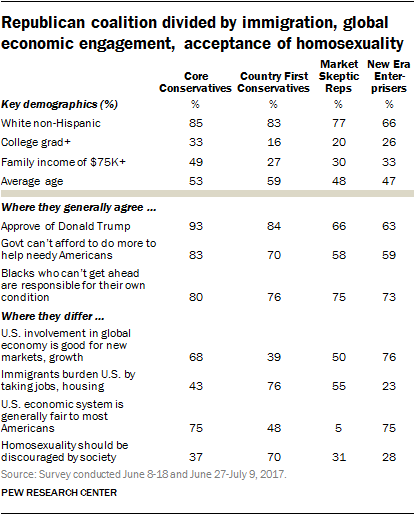

James Hohmann, in the Washington Post, looked at a recent, and very large, survey by the Pew Research Center. The survey identified four basic groups within today's GOP coalition, Hohmann writes:

Core Conservatives, about 15 percent of all registered voters, are what we think of as traditional Republicans. They overwhelmingly support smaller government, lower corporate tax rates and believe the economic system is fundamentally fair. Seven in 10 express a positive view of U.S. involvement in the global economy "because it provides the U.S. with new markets and opportunities for growth." ...

Country First Conservatives, a much smaller segment of the GOP base (7 percent of all registered voters), are older and less educated. They feel the country is broken, blame immigrants for that and largely think the U.S. should withdraw from the world. Nearly two-thirds agree with the statement that, "If America is too open to people from all over the world, we risk losing our identity as a nation."

Market Skeptic Republicans (12 percent of registered voters), leery of big business and free trade, believe the system is rigged against them. Just one-third of this group believes banks and other financial institutions have a positive effect on the way things are going in the country, and 94 percent say the economic system unfairly favors powerful interests. Most of them want to raise corporate taxes, and only half believe GOP leaders care about the middle class. They generally view immigrants negatively, they're not too focused on foreign affairs and they're less socially conservative than the first two groups.

New Era Enterprisers, the fourth group, are the opposite. They account for about 11 percent of registered voters: They're younger, more diverse and more bullish about America's future. They support business and believe welcoming immigrants makes the country stronger.

I issue a caveat: This is how people describe themselves and their views to a third party. It is easy to see how race and religion play a role in some of these categories, but the categories themselves underplay the degree to which race and religion are dominant shapers of voters' worldviews.

When Hohmann observes that "Trump's core supporters tend to regard economic policy as a zero-sum game," he is on to something important, but how useful is the observation if it could also be made about Occupy Wall Street protesters? I suspect the commitment of the "core conservatives" to free trade has something to do with their confidence in, and involvement with, corporate America that profits from so-called free trade. It is remarkable that none of the four categories requires any sense of optimism, still less altruism.

In any event, the latest Gallup poll, which recently had Trump at a record low of 33 percent among all voters, nonetheless shows him still earning a 78 percent job approval number from Republicans.

In September, a CNN poll showed that Republicans were turning against the leaders of their party in Congress, but not against Trump. No matter the reasons, no matter the categories, the GOP is Trump's party now. I note that both polls were taken before the indictment of top Trump campaign aides.

Michael Gerson, who has been the most consistently precise moral critic of Trump from the right, recently assailed Trump for undercutting one of contemporary conservatism's principal objectives: beating back relativistic understandings of truth. After recalling Allan Bloom's famous book The Closing of the American Mind, which raised the alarm about the relativism Bloom found among his students, Gerson writes:

Conservatives were supposed to be the protectors of objective truth from various forms of postmodernism. Now they generally defend our thoroughly post-truth president. Evidently we are all relativists now.

Not quite all. Some of us still think this attack on truth is a dangerous form of political corruption. The problem is not just the constant lies. It is the dismissal of reason and objectivity as inherently elitist and partisan. It is the invitation to supporters to live entirely within Trump's dark, divisive, dystopian version of reality. It is the attempt to destroy or subvert any source of informed judgment other than Trump himself. This is the construction of a pernicious form of tyranny: a tyranny over the mind.

This particular tyranny resonates comfortably with white evangelicals, who are the real core of Trump's supporters, and whose commitment to "reason and objectivity" has never been their strong suit. "I am more interested in the Rock of Ages than I am in the age of rocks," said the fictional version of William Jennings Bryan in the movie "Inherit the Wind." We Roman Catholics can assent to that statement as it stands: It is better to know the Rock of Ages. But we Catholics want to know why we must choose. Can't we know both?

Denying evolution made evangelicals easy prey for the Koch brothers and their efforts to deny climate change. The radical subjectivism of evangelical Protestantism makes many of its adherents susceptible to the propaganda coming out of Fox News.

I hope there are enough Republicans like Flake and Gerson to someday reclaim the GOP. A great nation needs a conservative political party to keep its political life balanced.

Today, there is no conservative party in any meaningful sense of the word. Trump killed that party. Instead, Trump has helped today's GOP climb onto the back of the tiger of resentment and racially driven populism, and when you ride on the tiger, you go where the tiger wants to go.

This is what the Republicans have learned: Their winks at racism helped keep alive some of the ugliest impulses in American culture, and all it took was someone like Donald Trump to throw a match onto the kindling. If they do not find a way to distance themselves from this man, and drive a different message to their core supporters, the fire will consume them too.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest! Sign up to receive free newsletters, and we will notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.