University of Notre Dame professor Patrick Deneen declares that "another world is possible" in a talk he delivered during a Oct. 7-8, 2022, conference, "Restoring A Nation: The Common Good in the American Tradition," at Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio. (NCR photo/Brian Fraga)

Integralism is the latest iteration of right-wing zaniness in Catholic circles. It is different from the other more populist expressions of reactionary Catholicism in part because it is proposed by brilliant scholars such as Harvard University's Adrian Vermeule and University of Notre Dame's Patrick Deneen. Political philosopher Steve Schneck recently reviewed Deneen's latest book for NCR and NCR staff reporter Brian Fraga wrote about a conference at which Vermeule spoke.

The integralist movement is not univocal, but its various proponents share a common critique of liberalism and look to past regimes that united church and state as a preferable alternative. The more benign rationale for uniting the ecclesial with the temporal realms is that government seeks the common good and the supernatural good should not be a priori excluded from the common good.

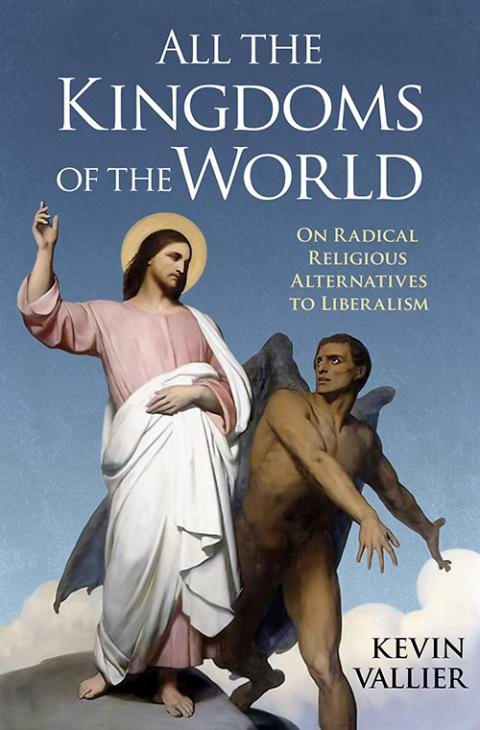

The more accurate, and frightening, rationale is that demonic forces seek to rule the world, and that the church, in order to establish the kingdom of God, "must contest demonic rule and seek the spiritual governance of the entire world. … The church cannot abandon earthly rulers to stand alone against the darkness," as Kevin Vallier explains in his new book from Oxford University Press, All the Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism.

It is not an easy read, fluctuating between academic verbiage and a chatty, conversational style, and tackling an admittedly difficult and abstruse topic. It is nonetheless an important read because none of us yet knows how influential these integralists will become and because Vallier takes the movement seriously.

Integralism did not just happen. It grows out of a crisis in liberalism. "The integralists have given a voice to young Christians, many of whom have grown up alienated from their institutions," Vallier, who teaches at Bowling Green State University, writes. "These young people, often on the political Right, are not traditional small-government conservatives. They are not especially enamored of the Constitution, and they do not care about reading it according to original public meaning."

Vallier does not use the word, but it popped into my head reading those sentences: sophomoric. In our time, alas, sophomoric thought does not keep one from the highest positions of political power nor from prestigious posts in academic life.

Vallier's analysis of liberalism rings true, even if it is depressing. He writes:

Today liberalism has become associated with abstract academic theorizing. Liberals obsess over esoteric debates about sex and gender that make no sense to most humans. The authoritarian leaders of the world have noticed, eagerly pointing out liberal insularity. Consider the bizarre spectacle of Russian president Vladimir Putin complaining that transgender activists have mistreated famed children's book author J.K. Rowling. Why does Putin care? He doesn't. He wants to delegitimize liberal order by drawing attention to its flaws.

Vallier's next sentence — "In most places, liberalism was a practical program of reform" — put me in mind of philosophy professor Martha Nussbaum's brilliantly savage takedown of Berkeley professor Judith Butler for leading liberalism — and feminism — astray. When liberalism became performative rather than practical, it began the long process of alienating itself from the working class, paving the way for integralism — and for Donald Trump!

The integralist response to liberalism's flaws is, like Trumpianism, brutish. But while Trump's vision has a certain cultishness to it, it lacks any rootedness in religious theories and beliefs. Trump is too solipsistic to engage theology; he is the only god permitted into his tent.

Harvard Law professor Adrian Vermeule speaks on the American administrative state during a Oct. 7-8, 2022, conference, "Restoring A Nation: The Common Good in the American Tradition," at Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio. (NCR photo/Brian Fraga)

Vermeule and the other integralists "draw on ancient and sophisticated theologies." Vallier — and scholars like Pepperdine University's Jason Blakely — make it their job to rescue Catholic theology from the deformations the integralists perpetrate.

Vallier explains the rise of Vermeule within the movement and why his rise is significant, in part because of his reputation as "one of the world's leading scholars of administrative law," and in part because Vermeule "found a powerful digital voice." Vermeule resists the "localism" that Deneen advocates, because it is too modest in its ambitions. Vallier writes:

Vermeule means business. Catholics must find "a strategic position from which to sear the liberal faith with hot irons, to defeat and capture the hearts and minds of liberal agents, to take over the institutions of the old order that liberalism has itself prepared and to turn them to the promotion of human dignity and the common good." Vermeule's strategy, "integration from within," had been born. Integralists now distinguish themselves from all other postliberals for they defend a radical ideal and have a plan to reach it.

Vallier traces the historical arguments the integralists muster, but they are exceedingly weak.

Vallier also sometimes makes claims that are difficult to support. For example, he writes that, in the wake of the French Revolution, there emerged "two strands of conservative thought: the anglophone conservative tradition of Edmund Burke (1729-1797) and the European conservative tradition of Joseph de Maistre (1753-1821). The Burkean strand has dominated in the Anglosphere ever since."

Not in the U.S it hasn't. American conservatism has historically been pro-business and libertarian. I know a few American conservatives who put one in mind of Burke, but they are few indeed.

Advertisement

Of course, a key teaching of the church stands in the way of the integralists' agenda: In Dignitatis Humanae, the Decree on Religious Liberty issued by the Second Vatican Council in 1965, the Catholic Church officially endorsed religious liberty. Vallier does an excellent job explaining the debate at Vatican II about religious liberty, that the council did not merely baptize the American constitutional system, that the text left some ambiguity between a negative and a positive conception of liberty, between a "freedom from" and a "freedom for."

Vallier also does a fine job explaining how the integralists get round this obstacle by emphasizing the ambiguities in Dignitatis Humanae and resolving each of them in favor of the pre-conciliar teaching that rejected church-state separation as an inferior model to church-state union.

I wish he had done a more thorough job of explaining how deadly the ahistorical approach that characterized the pro-conciliar Roman theology was, and why it had to fail of its own volition. It spoke to a world that no longer existed. The conservative opposition at Vatican II still conceived of the church as a perfect society, even though all of Christian Europe had experienced two world wars and the Shoah, and the "perfect society" had been unable to stop it.

I recognize the difficulties in Dignitatis Humanae, but the position advocated by its opponents was not just outdated. It had proven itself utterly inadequate to the times.

I will conclude this review on Monday.