Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, in blue, is pictured doing community outreach to the Bengali community in New York's 14th congressional district. She is the U.S. Representative-elect for this district as of the Midterm Election Nov. 6, 2018. (Corey Torpie)

It has been exciting and gratifying to watch the mid-term election returns.

The much-vaunted "blue wave" finally materialized, bringing with it a newly energized hope that presidential accountability could at last be at hand. Democrats won a comfortable majority in the House of Representatives, and women made it happen.

So many female Democrats were elected that the "blue wave" has been dubbed a "pink wave."

Democratic women flipped 21 of the 23 Republican-held seats the Democrats needed to win control of the House. At this writing, at least 101 women have won House seats compared to the previous all-time high of 84. Women will make up 37 percent of Democratic members in both houses of Congress compared to just 6 percent of Republicans.

It is exciting that more than a third of women elected to federal office on November 6 are women of color.

A record number of women — 785 to be exact — ran for Congress. This accounts for 23 percent of congressional candidates, an increase from 16 percent in 2016. Of those 785 women, 517 were Democrats.

Many more women ran and won in state and local offices. For example, Michigan voters elected Democratic women to every statewide office, including governor, attorney general and secretary of state, as well as U.S. senator.

All of which leads me to wonder if this could be a silver lining to Hillary Clinton's devastating defeat. Or a deafening response to Donald Trump's virulent misogyny. It is probably both.

The Jan. 21, 2016, Women's March was highly influential in helping women realize that no one was going to stand up for us if we do not stand up for ourselves.

But way back in the 1980s, Catholic sisters were already pioneering women in political office. They ran and were elected at a time when female politicians were few and far between.

After Vatican II, sisters joined the civil rights movement, engaged in advocacy for women's rights, and worked to incorporate minorities into formerly white male enclaves such as the faculties of colleges and universities.

Advertisement

Sisters took to heart Catholic social teaching from the Vatican II constitution "The Church in the Modern World;" the 1971 Synod of Bishops' letter "Justice in the World," and Pope Paul VI's ringing challenge to religious in Evangelica Testificatio, "How then will the cry of the poor find an echo in your lives?"

It became obvious that political ministry was (and is) an important means of advocating on behalf of those made poor. So Catholic sisters ran for elected office and accepted political appointments. This was permitted at the time, provided the sister's religious community leadership and the bishop agreed.

Mercy Sr. Elizabeth Morancy was elected to the state legislature of Rhode Island in 1978 and re-elected in 1980. She was praised by civic groups and received a commendation from the bishop for her commitment to the poor and those on the margins.

In May 1982, Mercy Sr. Arline Violet announced her candidacy for attorney general in Rhode Island, an office she would win in 1985, becoming the first woman elected as a state's attorney general.

St. Joseph Sr. Clare Dunn served as minority leader in the Arizona legislature until her untimely death in a car accident in 1981. Dominican Sr. Ardeth Platte, who is probably best known for serving prison time for peace activism, was city councilwoman in Saginaw, Michigan, for over 10 years.

After being defeated in a bid to serve in the Michigan legislature, Mercy Sr. Agnes Mary Mansour was appointed to serve on Governor James Blanchard's cabinet as the Director of Health and Human Services (HHS). Michigan was in the throes of a severe economic downturn, and the poor were especially hard hit.

As did many other states, Michigan's health department allowed public funding of abortions for poor women at the time. Detroit's then-Archbishop Edmund Szoka had initially given Mansour permission to accept the appointment as long as she publicly expressed her personal opposition to abortion, which she did. But after unrelenting pressure from pro-life groups — and probably the pope — he reversed himself. He demanded that she publicly oppose Medicaid payments for abortion or resign as director.

Since Mansour had already accepted the appointment in good faith, and since both abortion and public payment were legal, she felt obliged in conscience to follow the law. Two Catholic laymen had previously served as directors of Michigan's health department, and neither had been targeted by pro-life activists. Nor had the cardinal demanded that they publicly oppose Medicaid funding or face church sanctions.

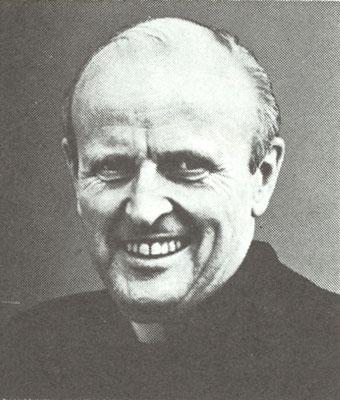

Jesuit Fr. Robert Drinan, pictured between 1970 and 1980 (U.S. House of Representatives)

Perhaps the best-known Catholic in public office at the time however, was Jesuit Fr. Robert Drinan, a five-term U.S. Congressman from Cambridge, Massachusetts. His political ministry had been sanctioned by Pope Paul VI, the U.S. episcopate, the cardinal of Boston and his own Jesuit superiors. In 1980, Pope John Paul II ordered him to resign. The pope had listened to conservative Republicans, who were rankled by Drinan's Democratic voting record, which they viewed as too "soft" on abortion.

Several years later, John Paul II would change an initial draft of the 1983 Code of Canon Law (still the current law of the church) from one that permitted political ministry to one that forbade it. Mansour, Morancy and Violet were forced out of the Sisters of Mercy for refusing to abandon their political ministry in service of those made poor.

From Morancy's perspective, political and cultural issues had influenced the Polish pope's action: "I think no one will deny that one of the most political persons in the world would be our current Pope. But out of the East European experience and culture, his vision is government as the enemy.''

The extent to which Catholics of good will can differ in addressing complex public policy issues such as legalized abortion, war and capital punishment was widely discussed then (as now) by moral theologians, churchwomen, churchmen and Catholic activists. A review of the recent history of Catholic differences over the Affordable Care Act and prelates who sought to deny Communion to Catholic politicians indicates this is by no means a dead issue.

While Catholic sisters and priests may (rightly or wrongly) no longer exercise their moral and social justice advocacy by serving in political office, Catholic laity can and must. And some have — wonderfully so.

Almost exactly nine years ago, Nancy Pelosi skillfully shepherded the Affordable Care Act through the House of Representatives, thereby providing health care to millions of Americans who previously had none. My own U.S. representative, Marcy Kaptur, can always be counted on to fight for working people and the poor. These women — and many Catholic men such as John Kerry, Joseph Biden and Chief Justice John Roberts — have found ways to negotiate the complexity and, at times, the moral ambiguity, that inevitably accompanies political office.

In responding to the Mansour situation, theologian Monica Hellwig once brilliantly observed:

Redemption is restoration of all things in Christ. … To participate in the restoration is necessarily to participate in ambivalent situations, in structures that are not morally and spiritually perfect. … If there are structures of sin then there are also structures of grace; those structures that move toward the overcoming of cultural, racial, and political barriers … that challenge and overcome oppression and greed, that redress the balance of power and resources in favor of the poor and excluded. To participate in such structures is to cooperate with grace.

It is heartening to see some gender and racial barriers falling away in our political system, although we still have a long way to go.

Perhaps the fresh vision of our new legislators will help Congress again take seriously the challenge of overcoming oppression, greed and racism to redress the balance of power.

Perhaps then God's healing grace will flow more freely throughout this troubled land.

[St. Joseph Sr. Christine Schenk served urban families for 18 years as a nurse midwife before co-founding FutureChurch, where she served for 23 years. She holds master's degrees in nursing and theology.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Christine Schenk's column, Simply Spirit, is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.