Pope Paul VI's address to the U.N. General Assembly in New York City in 1965 is depicted in a stained-glass window at the Immaculate Conception Center in Douglaston, New York. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Pope Paul VI was the kindly priest with a liberal heart and a conservative soul, an irreconcilable duality, as was his dual role as pope and as presider over the final three sessions of the reforming Second Vatican Council (1962-65).

He was, when globetrotting, like Mr. Rogers, loving, open, at ease — and yet, like Mr. Rogers, never relinquishing that innate reserve. Some in the Vatican press corps dubbed him "Hamlet," pensive, hesitant, at times almost dithering, a man lost in thought who, as time progressed, displayed a sense of failure in the deep lines of sadness etched into his face.

Paul could not win because the tradition of the Church-in-Rome (popes, College of Cardinals, Curia and senior global archbishops) contradicted the people he loved as "the pilgrim pope." That contradiction is what I want, finally, to concentrate on.

By happenstance, I'd followed Paul every step of his way. When he was elected, in June 1963, I was writing for the Catholic Star Herald of Camden, New Jersey.

As he flew into New York, so did I. Full-time at college, I commuted from Oxford to Fleet Street two and three days a week to the Catholic Herald, whose editor, Desmond Fisher, dispatched me to New York for the U.N. visit.

When Pope Paul VI died, I was editor of National Catholic Reporter.

Even as Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, he was the consummate Vatican insider; at 26, attaché in Poland's apostolic nunciature; at 40 undersecretary of state to Pope Pius XI.

His quality: The following year, he declined to be named a cardinal, an honor he delayed for two decades. He saw himself as truly a servant, not the more typical Vatican careerist.

NCR's Vatican correspondent Peter Hebblethwaite noted that when Milan's Cardinal Montini left for the conclave, he told his Milan assistant he would sign, when he returned, the documents under consideration. (Hebblethwaite's 1993 Paul VI: The First Modern Pope is the standard work.)

Pope Paul VI offers a blessing at Rome's airport before a flight to Istanbul in 1967. (CNS file photo)

My initial column on the New York visit, as memory serves, went (in those pre-PC days) something like this:

"Non-Catholic New Yorkers contend that when St. Patrick drove all the snakes out of Ireland, they traveled to New York and became cops. Fifteen thousand of them will be on duty when Pope Paul VI's motorcade travels to the United Nations. But this predominantly Catholic (Irish, Polish, Italian) police force won't see him. The police have been instructed to face the crowds they're holding back, in order to prevent a possible assassination attempt."

The pope saw the United Nations as the secular embodiment of everything the Catholic Church strove for on behalf of world peace; that Benedict XV (pope 1914-22) aimed for in his 1917 World War I seven-point "peace plan." Benedict called for arbitration as the goal to prevent, or end, hostility between nations.

Paul told the United Nations delegates, and the world,

Many words are not needed to proclaim this loftiest aim of your institution. It suffices to remember that the blood of millions of men, that numberless and unheard-of sufferings, useless slaughter and frightful ruin, are the sanction of the pact which unites you, with an oath which must change the future history of the world: No more war, war never again! Peace, it is peace which must guide the destinies of people and of all mankind.

Paul's greatest triumph was that U.N. visit, that: "Jamais la guerre!" ("War no more"). His lowest point: 1968 Humanae Vitae's continuation of the proscription on married Catholics using birth control, and his reinforcement of celibacy leaving priests to either quit or endure.

The U.N. was a first. It was stunning, it encouraged — and the world, in practice, ignored it. His encyclical Humanae Vitae was stunning, it discouraged — and most Catholics, in practice, ignored it.

Forty years ago, marking Paul VI's death, NCR pulled together an astonishing array of commentary on this essentially decent person. The general opinion was that history would treat him kindly. My friend, and NCR board member, Albert C. Outler, the Methodist minister and historian at Southern Methodist University, was disappointed that the Second Vatican Council -— where he had been a Protestant observer — had not approved intercommunion among Christians.

Nonetheless, Outler wrote that if it could be said that "Vatican II was a reforming council, then Paul VI was a reforming pope, and the post-Vatican II church owes him more than she has yet acknowledged. It is reasonable to wonder who else could have presided over Rome's transition from where it was in 1963 to where it is today, without still worse disruptions."

Servants of the Holy Heart of Mary Sr. Agnes Cunningham, writing on Humanae Vitae after Paul's death, could write, "the whole Catholic world, it seems, looks to the new pope with the hope he will be a spiritual leader without compromise, a pastoral leader without ambiguity. Such a leader would do more than attend to the consequences of Humanae Vitae. By that fact, he would address the issue of human life directly."

There was every indication that Cunningham was correct, that Pope John Paul I was such a pope. Alas. Dead in the Vatican after 33 days.

Advertisement

But in one sense it did not matter who was pope when it came to assessing how the church is governed, and how the words "tradition" and "church" were abused.

To my mind, the earthly miracle of Christianity is how, despite every obstacle and insult visited on them by the Church-in-Rome, the everyday folks who are the church have kept Christ's vision a living thing.

The Church-in-Rome — and this applies to Paul VI — for a millennia and a half and more, with billions of fine-sounding words, still managed to project a vision of church tradition that protects it. And project the mistaken image that it, the Church-in-Rome, is "the church."

Again, I stress that Paul VI did see himself as truly a servant, not a Vatican careerist.

Alas, he did not realize how deeply he was cast in the Vatican mold. For he could not see his inability take a detached view of the institution and those traditions that had formed him; in practice, his institutional backward glances stopped at Trent.

Nor did he dare speculate on what the people outside the Vatican, the everyday Catholics he reached out to in countries around the world, might hope the future could look like. As if he could reach out to them, but daren't reach into them.

Why not? The Church-in-Rome is a bureaucracy. A bureaucracy's first instinct is self-preservation.

More troubling, the Church-in-Rome has a millennia-and-more-long corruption virus running through it. By no means are all cardinals, archbishops and bishops affected by it.

Nonetheless, the disease is a constant mix of money-sex-power-privilege-and-self-protection. It is the apogee of misogyny and the old boys' club. Many cardinals really believe they are medieval princes, capes and trains and all, that the church is a form of royal court where they can play out their ambitions.

Consequently, the Church-in-Rome is a bastion of privilege and presumed entitlement. And worse.

When, in the Irish Independent in 2011, Dublin Archbishop Diarmuid Martin admitted there could be a "cabal" in the Vatican protecting sexual abusers, he wasn't referring to anything recently established.

There is no reason to think such protectionism didn't stretch back to the Medicis, and earlier.

That said, from the mid-1980s on, as I was trudging through the sludge that was the clerical pedophilia and bishops' cover-up crisis, I would periodically comment that if you think this is bad you should try following the money.

Pope Paul VI watches on television the first manned lunar landing July 21, 1969, at the Vatican Observatory in Castel Gandolfo, Italy. (CNS/Catholic Press Photo)

My first byline in NCR, in early 1975, was on Archbishop Paul Marcinkus and the Vatican bank. Marcinkus, Paul VI's bodyguard, nicknamed "the gorilla," who manhandled a would-be assassin away from the pope in Manila, the Philippines, was the cleric the pope put in charge of the money-laundering neighborhood bank.

Marcinkus admitted to NCR he'd never handled more money greater than "the collection plate." Curial congregations' money-handling was opaque, even nonexistent. An inquisitive L'Osservatore Romano could run to some effect an annual "Rich List" compendium of the net worth of moneyed retiring cardinals and archbishops. Who was on it and who wasn't.

Paul VI was a man of many firsts, first to visit the United States. His 50-minute visit with President Lyndon B. Johnson was informal — the Vatican hadn't had diplomatic relations since the mid-19th century, a breakdown based on anti-Catholic bigotry.

First to visit the Holy Land. First pope to visit India.

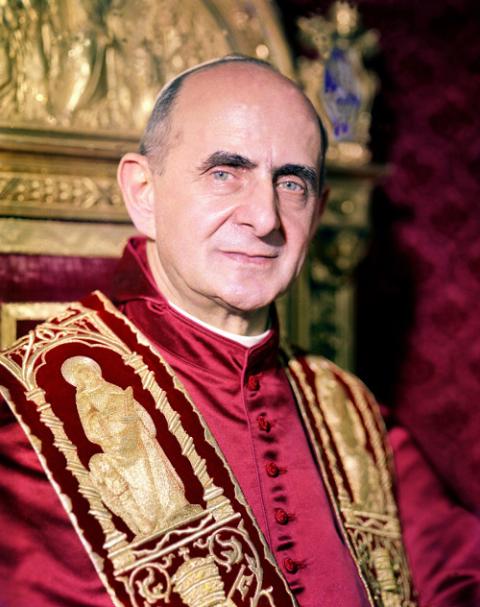

Pope Paul VI is seen in an undated official portrait. (CNS/Felici, Catholic Press Photo)

Never still. Never happier than when he was on the road. Yet in other ways, he was just one more in a long line of popes who used church "tradition" to protect the status quo.

That traditional vision, under Paul's watch, was evident when Vatican II approved Gaudium et Spes (Joy and Hope), the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. The London Tablet's cover read: "Neither Gaudium nor Spes."

We are all victims, captives, to our time. Time doesn't always deal fairly with the dead, the dead who in life, declared an opinion, took an action — as did Paul — and risked, as he "shuffled off this mortal coil … the whips and scorns of time."

Had Paul earned a few of Hamlet's "whips and scorns"?

Readying himself for death, the saddened Paul could have prayed: "O that this too too solid flesh would melt. Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew."

Looking at him, at the lines etched into his face, this was a decent man, a kind man. A man and pope trapped, professionally, in his time, in the Church-in-Rome and the tradition that shaped him.

Paul deserves we think kindly of him.

The final point: that "tradition" reveals the enormity of the challenge Pope Francis has set himself to root out the virus, in his valiant efforts to truly reform the Church-in-Rome, and explain to the world who is "the church."

[Arthur Jones was NCR editor for five-and-a-half years, from January 1975 to June 1980. He was NCR editor-at-large and had a parallel career as an international global economics and finance writer. His dozen books include Pierre Toussaint (Doubleday), and National Catholic Reporter at 50 (Rowman and Littlefield). His current work in progress is The Jesus Spy. He is also writing, under the pen name A.L. McAmi, a children's trilogy set in 19th-century Scotland.]