The Catholic Church could get its second Native American saint if a Vatican research trip to South Dakota this month leads to confirmation of two miracles performed by Nicholas Black Elk, a Lakota Sioux medicine man born in the Civil War era.

Fr. Luis Escalante, a Vatican postulator, or researcher for sainthood candidates, recently spent several days in western South Dakota gathering information about Black Elk's life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Escalante spoke with local advocates for the cause, including some who testified to the reportedly miraculous powers of a man who practiced traditional Lakota rituals and also baptized more than 400 Native Americans.

"It would be a big deal for the native people here: one of their own being recognized as a saint in the church," said Deacon Marlon Leneaugh, a Lakota tribesman who oversees native ministries for the Diocese of Rapid City. "The church has been here over 100 years, and this is an experience that they've never had before."

If canonized, Black Elk would become only the second Native American Catholic saint. Kateri Tekakwitha, a 17th-century Algonquin-Mohawk, was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012.

Last year, Bishop Robert Gruss of the Diocese of Rapid City secured the unanimous consent of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to begin the canonization cause for Black Elk. With phase one in a four-phase process completed, his candidacy is now overseen by the Vatican. Canonization requires that two miracles be attributed to his intercession. Observers say the process for Black Elk could take more than 10 years.

The fact that he's even being considered, despite having openly maintained his Lakota traditions alongside his Catholicism, suggests his contributions — and his identity as both Native American and Catholic — are more appreciated in the church now than they might have been in decades and centuries past.

Black Elk lived in a time when the federal government contracted with churches, including the Catholic Church, to operate Indian boarding schools with a goal to "kill the Indian in him and save the man" by teaching kids to renounce indigenous languages, dress, customs and other aspects of cultural heritage.

But today, Black Elk's ties to his Lakota Sioux traditions are part of the case for his sainthood. In a 2016 petition asking Gruss to pursue sainthood for Black Elk, grandson George Looks Twice said Black Elk did not reject his culture after he married a Catholic, was baptized in 1904 and took the name Nicholas.

He "practiced his Lakota ways as well as the Catholic religion," Looks Twice said. "He was comfortable praying with this pipe and his rosary, and participated in Mass and Lakota ceremonies on a regular basis."

That Lakota Sioux ceremonial pipe, called a "chanupa," now figures prominently in the case for making him a saint.

Aaron Desersa, a 65-year-old great-grandson of Black Elk and co-author of "Black Elk Lives: Conversations with the Black Elk Family," told Religion News Service his ancestor "believed in the connection of all the religions of this world." He said he knows firsthand of Black Elk's miracles, including two involving his wife, his mother and Black Elk's chanupa.

In 1995, "my wife had cancer real bad, and they gave her six months to live," he said. As custodian of Black Elk's chanupa, he decided it was time to use it. They prayed with the pipe at a traditional Lakota sun dance, he said.

"She's living proof today" of Black Elk's miraculous powers, he said. A year later, the cancer was gone, he said.

Advertisement

In 1999, Desera's mother had been told that X-rays showed she needed hip replacement surgery. But after the family prayed with the chanupa, doctors found nothing wrong with her hip, he said.

Bill White, a Lakota lay minister at a Catholic church on the Pine Ridge Reservation and coordinator of local efforts to canonize Black Elk, said he would look into Desersa's accounts. He cautioned that testimony of a family member might not be enough to validate a miracle, but it has value nonetheless.

"Even if it's not a bona fide miracle, it just proves that people are praying for his intercession," White said. "The more people who believe he's up in heaven, it's going to support the cause."

Black Elk was born in December 1863 near Little Powder River in Montana, according to "Black Elk Speaks," an autobiographical account that Black Elk dictated to writer John Neihardt. (Other accounts give 1866 as the year of birth.) At age 9, Black Elk was reportedly standing on a mountain peak when he had a vision that would guide his actions as an adult.

"I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being," the account reads.

For White, the fact that Black Elk had a vision of everyone living together as one at such a young age is what clinches the case that he should be canonized.

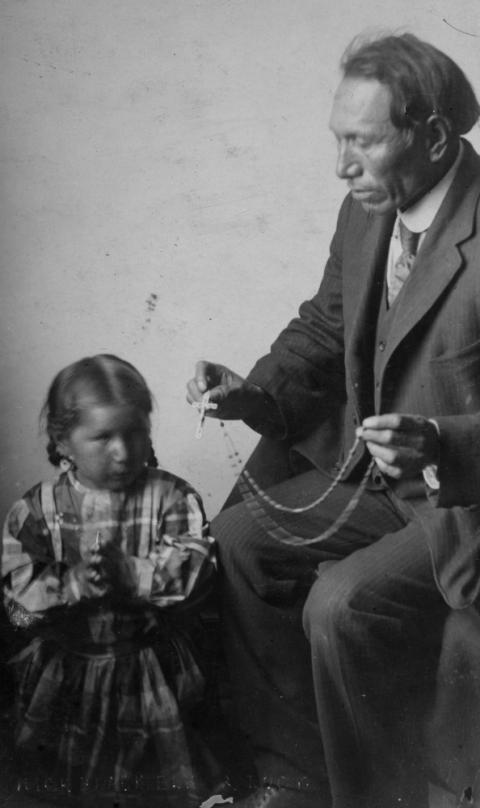

Nicholas Black Elk is pictured in an undated historical photo teaching a girl how to pray the rosary. (CNS/courtesy Marquette University)

"Hate was pretty rampant back then, so for him to get a message like that, I believe it was from God himself," White said. "Because that's the exact message that Jesus brought us."

But Black Elk was also a fighter. In June 1876, when he was 12 years old, he was present when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led 700 soldiers into battle against a vastly larger force of warriors from the Lakota and other tribes. In Neihardt's account of one war scene, Black Elk comes off more as warrior than saint.

"There was a soldier on the ground and he was still kicking," Black Elk says in "Black Elk Speaks." "A Lakota rode up and said to me, 'Boy, get off and scalp him.' I got off and started to do it. He had short hair and my knife was not very sharp. He ground his teeth. Then I shot him in the forehead and got his scalp. … I was not sorry at all. I was a happy boy."

Not everyone on the Pine Ridge Reservation, where many of Black Elk's descendants live, support the cause of sainthood for him. Critics include Black Elk's granddaughter Charlotte Black Elk, an attorney and environmental activist who said she views the Catholic Church as a cult. Becoming a Catholic catechist came with perks for Black Elk, she said, including a car that gave him more freedom than most. When asked if he should be made a saint, she said no, adding that she doubted he ever truly held Catholic beliefs.

"I am opposed to" the sainthood cause, she said, "but I'm not going to throw myself in front of it. It's important to some members of the family. And it's obviously important to the mission churches in Indian country, to have another saint."

Black Elk died in 1950. Nearly seven decades later, advocates say it's not too late to tap witnesses who remember the man.

"Now it's our role to find people who knew him," White said. "Or knew of him."