Interview with Bishop Gerald Kicanas

October 13, 2008

Bishop Gerald Kicanas of Tucson, Arizona, serves as Vice-President of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. This is the first Synod of Bishops for Kicanas, 67, and it hasn’t exactly been a walk in the park. Aside from the normal tedium of listening to hundreds of speeches, Kicanas is also suffering from a cold, and his beloved Chicago White Sox made an early exit from the baseball playoffs.

Despite all that, Kicanas sat down for an interview on Monday afternoon at the North American College. In addition to the synod itself, the conversation also touched upon preaching by laity, the looming elections in the United States, the global financial crisis, and a discussion of abortion and politics the U.S. bishops plan to have at their mid-November meeting in Baltimore.

The following is a complete transcript of the interview.

What has struck you about the synod so far?

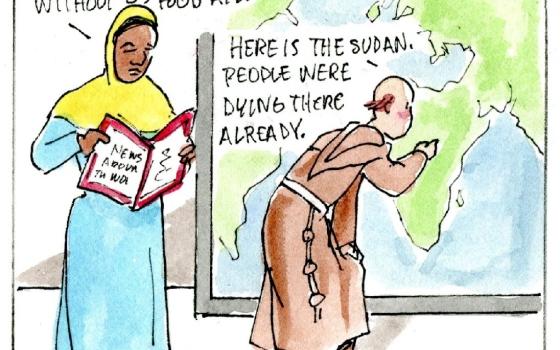

What’s fascinating is that everyone’s perspective is so different. Each person seems to pick a different section of the Instrumentum and offer their perspective, some from their own pastoral experience, some more theologically oriented, some with very clear action possibilities that the synod might consider. It’s fascinating, especially to hear bishops from ‘Third World’ countries, and the tremendous struggle that the church faces in those communities: great persecution, discrimination, poverty, illiteracy, things that we don’t experience so strongly in the United States. It’s interesting, and often very moving, to hear some of the observations that the bishops have made.

Is there anything concrete you’ve heard that you’ll take home, and that might make a difference in Tucson?

I think it’s been the ability to proclaim the Word of God in the liturgy in a more deliberate way. One person said today it’s like passenger trains and cars passing by. You hear the clank and the noise, but you don’t really pay attention. I think that’s true. People listen to the Word proclaimed at Mass, but if you ask them five minutes later what it was about, I don’t think they would have a clue. The question is how to make it more deliberate and more prayerful. Perhaps there should be more silence, to give people a chance to reflect on what’s been said. We’ve also talked about preaching and homilies. In some ways, every priest thinks he’s a great preacher, but you talk to the people, and sometimes they don’t think he’s so great. Whether homilies can be improved all that much I don’t know, but I think providing some opportunities for people to learn more about various ways of opening up the Word of God could be helpful.

Have you had any reaction to the idea you floated about designating 2009 as a ‘Year of Preaching?’

No, although there’s been a lot of talk about preaching, especially with regard to seminaries. It seems like we’re always going after seminaries to do something better, or more. There have been a few suggestions about finding ways to help priests and deacons to preach better. I think there will certainly be some propositions on preaching, and I hope that what I offered might be a possibility. It’s interesting to see how, when the universal church defines something as important, it begins to permeate the various dimensions and layers of the church. The Pauline year, for example, or a year of the Eucharist … all these things do have an impact in terms of what people think about and what they try to do during that year. So, we’ll see.

Part of your proposal was that priests and deacons sit down with laity to discuss how homilies can become more relevant. Is this something you’ve tried, and if so, what’s been your experience?

I’ve learned so much just by listening to laity speak about their struggles. Most recently, we’ve been doing it with parents, trying to see what concerns them, what the church might do to better support them. Of course, the constant theme is a concern that their children are not learning the faith. They believe that their children are not going to live as Catholics, as they’ve tried to live. It’s a preponderant concern among parents, how to form their children in the faith. Of course, faith is a grace, it’s a gift, it’s not something we can demand or insist upon. I think there’s an awful lot to be learned simply by listening to people, understanding what some of their struggles are, and how we can bring the Word of God and the faith we profess more directly into the lives of people.

There is a hunger, there is a struggle going on. These are terribly challenging days, even in our country, in the United States. There are fears and anxieties, for example related to what’s happening with the economy, and the church’s message could mean a great deal. How to do that is the big struggle right now.

I was recently at a Catholic conference on preaching, and one issue that surfaced there was preaching by laity. A number of laity, especially women, said they feel a vocation to preach, and they’re sometimes frustrated that this isn’t permitted during the Eucharist. What can you say to them?

I think there are opportunities for laity to preach, though they’re not liturgical moments in terms of the homily at the Mass. There are many times and places where laity can preach, and I think we should look for those opportunities and encourage them, because laity do have things to say. I think the issue is more in terms of the particular presiding role of the priest, and the responsibility to be the one who breaks open the Word of God at the liturgy in the homily. I think that’s not going to change. I think what can be developed and fostered more is finding extra-liturgical ways to encourage preaching by laity.

What would some of those ways be?

For example, at wake services or devotional experiences. Those are not moments when the preaching has to be done by the priest. I think those could be opportunities for the laity to use their gifts. Preaching retreats or days of renewal, things like that, are formative moments in people’s lives and very important spiritual opportunities. Preaching does take place by others in those settings, and, I think, in an effective way.

Is another possibility the media? When I was in Honduras, I met a lay Catholic preacher named Oscar Osorio, who has a very successful show on the national Catholic TV channel. He’s probably among the best-known Catholic preachers in the country, but he’s not a priest.

I think that’s right. We have not permeated the media in any effective way in terms of the preaching of the Word. I was out last night with Fr. Bob Barron, whom I think you know. [Note: Barron is a priest of the Chicago archdiocese who teaches at the University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary in Mundelein, Illinois, and is active in the media.] He’s working on a really significant project similar to “Civilisation” [an influential PBS series on Western history], which will be a ten-part series on the faith. He has some very fine producers who are working with him, and it will be about a $10 million project. They’ve been in Rome for about a week filming. They’ve been in Jerusalem, and they hope to go to Turkey and various other places. He’s a priest, obviously, but a good preacher who’s bringing his ability to image the Word in very powerful ways to a different format – not on the pulpit, but through the media. Hopefully, it will be quite an influential piece once it’s put together.

So your message to laity who feel a vocation to preaching would be that it can’t happen at the Eucharist, because of the sacramental theology that’s involved, but the church wants to hear their voice in a variety of other ways?

Sure. Every disciple ought to be preaching, first of all by the witness of their lives. Even in the family, I think in some ways preaching takes place – trying to bring to our children and grandchildren the message of Christ. We need to broaden our perspective, away from the idea that the only place preaching can take place is at Mass.

One of the tasks of a preacher is to connect the Word of God to the issues of the day. An issue very much on people’s minds these days in America is the election that will take place in three weeks. What points should preachers and pastors be making these days?

I think they’ve been helped greatly by the bishops’ document on forming consciences. [The document is titled “Faithful Citizenship.”] I think helping people to understand the document is important, because what you hear from people is that it’s too dense, we don’t understand it, it’s too complex, you should say things more simply. The reality, of course, is that the world is complex. These issues are not easy.

In some ways, the point of “Faithful Citizenship” was precisely to avoid simplistic reductions, wasn’t it?

Exactly. I do think, however, it’s important to make these things accessible to people. As the pope puts out encyclicals, I’ve been meeting with people to talk about them. I’ve thought about this in part because of the example of Monsignor [Reynold] Hillenbrand, who was the rector at Mundelein for many years. Under his leadership, a tremendous social consciousness formed among the priests of the Archdiocese of Chicago, because what he did was that he tried to teach the encyclicals and the other writings that were coming out during his day, many of which were on the social doctrine of the church. [Note: Hillenbrand was rector from 1936 to 1944.] I think there’s so much in these church documents – not all of them, but a good number of them – that could be taught more effectively in parish communities or even diocesan communities. The response has been very positive. Most of the people who came to these talks on Deus Caritas Est or Spe Salvi have never read the document. They walk away thinking, ‘Now I understand this a little bit. It sounds important, what the Holy Father is saying.’

Can you give a preacher who wants to address the elections a couple of bullet points?

The first point would be the importance of our responsibility as believers to take part in the public arena. That’s important for people to understand, that we don’t stay in the shadows, we don’t hide out, we have to respond as citizens. We are citizens of the United States, and we have a responsibility as disciples to help form our society. So, to vote is the first message. You have to see your faith as having a place in the public arena, which I think is something that some people question. They say this is not something the church should be considering or talking about.

Then, preachers can help people to understand the complexity of the moral issues that face our culture and our society. The idea, obviously, is not to support any particular candidate, but helping people to see that the church teaches the dignity of human life from conception to natural death, which involves a vast array of issues important in the community in which we live. It’s important to be able to speak knowledgably about those issues, and then to try to weigh the character of the person who is running for office – looking at the issues they propose, as well as their ability to put those issues into action, into legislation that will make a difference. It’s one thing to hold positions, it’s another thing to be able to get results. I think sometimes that’s discouraging, because people may propose positions that are along the lines of what we hold as a church, in terms of the dignity of human life, but they’re totally ineffective in being able to accomplish anything.

If I’m hearing you correctly, you’re saying that for a Catholic who wants to approach his or her vote in three weeks with the mind of the church, it’s not a slam-dunk which way that vote should go. Is that right?

Yes, and I think that’s what “Faithful Citizenship” is saying. As a disciple, as a citizen, you have to weigh issues, you have to consider the character of candidates, what you think they will be able to do in terms of affecting the society and the culture in which we live. Clearly, the document is saying that to vote for someone who is proposing actions that are intrinsically evil, because of their position on those intrinsically evil acts, is certainly problematic for someone who is a believer in Christ. You don’t believe in Christ and then vote for a person simply, or primarily, because they hold a position that’s contrary to the church. You have to take those positions into consideration, and then make a choice. These are never easy choices.

At the fall meeting, which comes shortly after the elections, the U.S. bishops plan to discuss abortion and politics. What’s that discussion about?

I think there are several issues. One is, what is the level of cooperation involved in a legislator voting for legislation that encourages, or allows, intrinsically evil acts? Is that formal cooperation, or isn’t it? That’s a critical question, because if it is formal cooperation, then serious consequences flow from it.

You mean automatic excommunication?

Right. That’s one question that has not been answered.

[Note: The Catechism of the Catholic Church states in article 2272: “Formal cooperation in an abortion constitutes a grave offense. The church attaches the canonical penalty of excommunication to this crime against human life.” Generally agreed-upon examples of “formal cooperation” might include the individual who had the abortion, and the doctor who performed it. There’s debate, however, about whether more indirect roles should be included. For example, last year an auxiliary bishop in Austria caused a stir by suggesting that a businessman who rents space to an abortion clinic is guilty of “formal cooperation.” More commonly, there’s debate about whether politicians who vote not to restrict abortion, or to widen its legality, are guilty of “formal cooperation.”]

Do you think there’s a consensus in the conference on whether a pro-choice vote, in itself, amounts to formal cooperation?

No, I’m sure there isn’t. There may not be anything the conference itself will be able to decide on that issue. It’s really a larger question.

Another question is, what should be the response of a bishop who has dialogued with a politician who holds intrinsically evil positions in terms of voting? What should be the response? As you know, some bishops are saying that communion should be withheld from those politicians. The bishops as whole left that question open, and it’s still a question that is left to the prudential judgment of the bishop in the local area.

I think what gets confusing for people is that the bishops aren’t of one mind on these questions. Therefore, they feel confused, and at times I think they try to pit bishops against one another, which isn’t helpful.

On this second point, about the denial of communion, do you see a growing consensus?

What’s still the normative document of the conference is that it’s a matter for the judgment of each local bishop. Whether that will change, I don’t know. I would think that probably it won’t.

So you’re having this discussion to see where things stand now among the bishops?

Yes, and I think it’s important that the discussion is taking place after the elections. If we did it beforehand, it could only be misused. That’s one of the difficulties, which is trying to state our teaching in a way that is not misused, or used in a partisan way, in a way that’s not intended by the teaching. This is an opportunity to air an important question, to give bishops an opportunity to state their positions, and to see where we are as a conference related to this. Of course, each bishop is responsible for his own diocese. Bishops put out different statements for their own situations. It’s an opportunity to air our thoughts, feelings, concerns.

Sitting here today, you don’t see a clear, overwhelming consensus on either of the points you’ve mentioned?

I don’t think there is a consensus. It’s an opportunity to go back to the question that we talked about several years ago, and see if there’s a different understanding we have as a conference, or whether we will reaffirm where we’re at. It may be that there won’t even be an action item, it may simply be an opportunity to talk. Maybe, out of that talk, some consensus will emerge.

It does seem there is one relevant difference between ’08 and ’04 on this question. In ’04, the question seemed to be: What should the church do about a politician who doesn’t follow Catholic teaching? This time around, it seems the question is more: Does following Catholic teaching automatically mean overturning Roe v. Wade, or is there another way of trying to combat abortion? Will that be part of your discussion?

Someone told me once that they think the legislative question is lost, both in terms of same-sex marriage and in terms of abortion, and that what the church should be focusing its energies on is changing the thinking in order to lead people not to choose abortion. I certainly think there’s some importance to that. We may find ourselves hamstrung in terms of our capacity to change legislation, or the thinking of legislators. Yet we can still work to make our teaching more influential in changing people’s thinking, helping them to see that there are alternatives, there are opportunities to find support, whether it’s financial or whatever – whatever the pressing concern is that leads to a decision as a difficult as it is, to abort a child. I think we need to do both, in some ways. I don’t think we can give up on the legislative challenge, but I think we have to work more intensively to try to change the thinking of people, to help them understand why the church teaches what it does.

To build a grassroots culture of life?

Right.

Some argue that you can be genuinely opposed to abortion, yet as a matter of prudential judgment believe that it would be counter-productive to try to make abortion illegal. Do you think it’s possible to reconcile that with the teaching of the church?

It depends on how the person is thinking through that as a legislator. It’s complicated. I think that our encouragement to legislators who are Catholic, and who are voting for pro-choice legislation, is to emphasize the importance of the fact that the church sees these acts as intrinsically evil. It’s not something that we can wink at, or take lightly. I think it’s a both/and. We have to keep working at creating a society in which the law doesn’t support an act that is intrinsically evil, but even perhaps more important, and in the end, more effective, is changing the thinking of people in how they approach this terribly difficult decision.

Finally, for preachers who feel they have to say something about the economic crisis, can you offer a couple of talking points?

One of the things the Holy Father said is something a homilist might consider: In whom do we place our trust? In what do we place our trust? For so many of us, I think we put our trust in success and in affluence, in these things that seem so secure, but all of a sudden we realize they’re not so secure. So, where do we place our trust? I think this is a moment to help people see that life is always insecure, that it’s never going to be without suffering, disappointment, and failure. Through all of that, we find our anchor in Christ, in the person of Jesus, in whom we believe.

Any other point you want to make about the synod?

It’s my first time. It can be tedious, but it’s also really quite moving sometimes listening to the comments from bishops. I’m looking forward to the small groups. We’ve only met once, but we have a really fine group. It was quite an engaging conversation, so hopefully it will be more of that.