(Unsplash/Nikita Andreev)

The money of the United States bears the official national motto: "In God We Trust." It's a curious and sometimes contentious part of our history. Apparently, the motto first appeared on coins during the Civil War, a not so subtle assertion that God was on the side of the Union. During the height of the Cold War, when the atheistic Soviet Union was our most frightening enemy, Congress passed laws making the phrase the official motto of the United States and ordering that it should be printed on all U.S. paper currency.

When the motto and its exhibition have been challenged in court, the decisions have ruled that it does not favor the establishment of religion and therefore is not unconstitutional. A 2004 Supreme Court ruling about references to God in the Pledge of Allegiance noted that "any religious freight the words may have been meant to carry originally has long since been lost."

On the other extreme, President Teddy Roosevelt called references to God on coins "irreverence, which comes dangerously close to sacrilege." God and country, church and state, the debate has confounded Christians since the time of Jesus.

In today's Gospel, we see the start of a strange alliance between Pharisees and Herodians, groups whose only commonality seemed to be their opposition to Jesus. In one sense, they might be taken as the representatives of strict religion and the folks who could drop all scruples and self-servingly support the local dynasty. When this odd combo of church and state factions questioned Jesus about the legitimacy of paying taxes, they thought they had come up with the perfect dilemma.

If Jesus said, "Pay," he implicitly acknowledged the legitimacy of the Roman occupation, pagan rule over God's people. On the other hand, those people remembered that less than 30 years before this happened, a man called Judas the Galilean had been executed for starting a revolution based on refusing to pay taxes. His sons met the same fate in the year A.D. 47. Tax resistance was dangerous in those days.

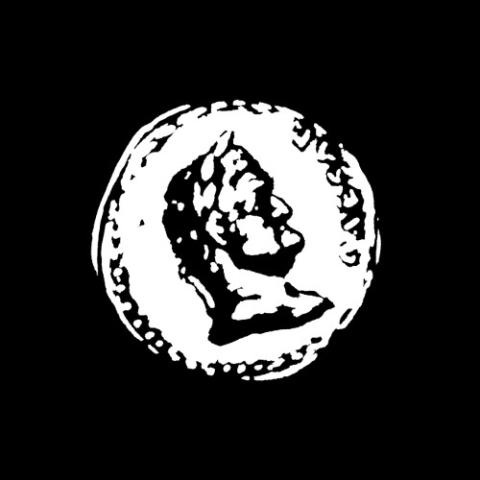

Jesus was never one to be bested in political theater. Just when they thought they had him on the hook, he reeled them in. It was time for show and tell. He asked for a coin. Whose picture was on it? The coin they carried displayed not only an image of Tiberius Caesar but also a written declaration that he was the son of the divine Augustus. The other side of the coin had the words pontifex maximus declaring that Caesar was the most high priest. The very sight of such a coin would rankle strongly religious or nationalistic Jews. For the Gospel writers, the memory of the coin was the height of irony.

Then Jesus responded to their interrogation. When they admitted that the coin bore an image of Caesar, he handed them a riddle: "Repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God."

(Mark Bartholomew)

Jesus' response would satisfy no purist. The righteous religious would see him as promoting capitulation to the pagans. The Herodians, the "if you can't lick 'em, join 'em" crowd, would realize they had just been given a very tenuous pass. The underlying question is what could belong to Caesar that does not already belong to God? Jesus left it to each age to discern how to interpret that for their own times.

The Gospel gives us Jesus' response to groups that were out to trap him. What about folks who are sincere in wondering when supporting Caesar stops being legitimate? When must we be conscientious objectors? There are a few details in the story that offer clues to the riddle. First of all, any practicing Jew who heard Jesus say something about what belongs to God would have heard echoes of prayers like Psalm 24, which begins, "The earth is the Lord's and all it holds, the world and those who dwell in it."

The second hint comes through the part of the story that Jesus didn't emphasize. The coin the questioners were carrying was blasphemous to religious Jews. It symbolized all the institutions that tend to divinize themselves as the ultimate in importance or authority. The inscription on the coin could be compared to the statement, "My country, right or wrong," or any other declaration of absolute allegiance to anything on the Earth. That inscription and attitude cross the line, giving to Caesar what belongs to God. Seen in that light, an answer to the riddle begins to appear. Caesar, the common good, society, can all make legitimate claims on us. We are responsible to create societies that serve the good of all. That's what we owe to Caesar.

Advertisement

If the God in whom we trust is the God of Jesus, what we owe to God is a blank check.

[Mary M. McGlone, a Sister of St. Joseph, is currently writing the history of the Sisters of St. Joseph in the U.S.]