In recent election cycles, the subject of poor people was considered one of those "third rail" issues in which politicians could perceive only disadvantage. The closest anyone got to discussions of growing poverty and alienation in U.S. society was predictable, broadly safe talking points about the middle class.

Poverty, however, seems to be poking through the usual political noise and emerging in new ways.

Reframed primarily as a problem of growing income inequality, the discussion has even ventured into another issue avoided at all costs on the political stump: class. Whether poverty and class divisions make it into debate questions and candidate talking points as we head toward the presidential election of 2016 is quite another matter, but the issues have taken a serious turn toward the mainstream in recent weeks.

Class, of course, isn't supposed to be a problem in America. Who you are and who you can become should not be defined entirely by your ancestry, neighborhood or parents' bank account. Inequality, however, has reached such proportions that it apparently is rattling consciences across some political and ideological divides.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, in joining Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio in their "agenda for growth and shared prosperity," said everyone is "so focused on inequality all of a sudden" because "it's gotten so much worse."

In an ambitious and packed three-day summit on poverty sponsored by Georgetown University's Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, Harvard Professor Robert Putnam's argument that poverty has taken on the added burden of class distinction served as a foundational explanation of the state of things today. His recent book, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, paints a distressing portrait of American culture so changed over the past half century that wealth defines place as never before, segmenting portions of the culture off from one another in unprecedented ways.

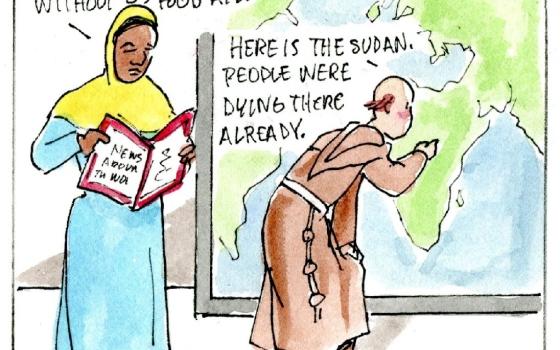

To borrow a central thought from Pope Francis (whom Putnam, self-described as not religious, referenced), what's lacking is encounter with and a sense of caring for those outside our small socioeconomic universes.

What is fascinating about the current discussion, aside from the fact that it is even occurring, is that both the description of the growing divide and its solution are initially spoken of not in terms of policy options but in terms of relationships. That alone -- recalibrating the discussion from one of red and blue politics (it'll get there soon enough) to one of how we relate to one another -- is, alone, worth the effort.

Francis' call to encounter was explicit in the message of a meeting of PICO National Network affiliates and social justice advocates from around the country gathered in Philadelphia in mid-May. The group produced a study guide, Year of Encounter With Pope Francis, that is designed to move people to action on such issues as immigration, criminal justice and racism. The goal is to reach 1,000 Catholic parishes in 75 dioceses during the next year. "This is a kairos moment within the American Catholic church and society, and with the pope's visit imminent, a moment of grace," said one of the participants.

While there are some unknowns regarding what the pope intends to do during his trip to the United States in September, it is clear that the principal topic is already in place. The PICO gathering drew Honduran Cardinal Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga, chair of the pope's Council of Cardinals, and his presence certainly amplified the importance of the theme of encounter with the poor.

The problems of poverty and income disparity are so huge that no single answer is adequate. Ultimately, government policies and legislation will have to play a role. If that seems an impossibility in the current climate, perhaps the initiatives outlined above are taking the correct first steps by moving us to recognize our economic segregation, the danger in such divisions and the need to encounter those across the divides as neighbors.

We know from experience -- think of racial segregation, gay rights, women's equality -- that encountering others as people rather than abstract issues is what leads to understanding. And solutions follow.