The word archives conjures an image of a dark room with file cabinets, covered in dust, filled with papers that are delicate, containing fading, often illegible writing, all of it overseen by an ancient cleric who is greatly concerned to make sure that no one enters his precinct with a ballpoint pen.

Maria Mazzenga, archivist for The Catholic University of America in Washington, is out to shatter that image. I first met Mazzenga at the frequent brown-bag lunches hosted by the university’s Institute for Policy Research & Catholic Studies, where we are both fellows. She can scarcely contain her enthusiasm about the university’s collections, which include the papers of famous churchmen like Msgr. John A. Ryan, and also the papers of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Mazzenga, who became Catholic University’s archivist in 2005 and earned her doctorate in U.S. history at the school as well, believes that the work of trained archivists and librarians is more important than ever in today’s Web-driven information culture. “You think you know from a Google search,” she said, “but do you really know where the information is coming from?” She explained that some sites are moderated by archivists with training in their field and other sites are designed to serve what she considers “ideological ends.” An archivist needs to determine “which resources are historically accurate and which aren’t.”

Maintaining professional standards of historical accuracy is especially important as Mazzenga and others decide which documents to digitize and make available on the Web. Different reasons drive the decision-making process. For example, the papers in the Fenian Brotherhood Collection were so delicate and so popular that digitizing them will help preserve them from damage caused by overuse.

Other times, current issues drive the decision to digitize. Mazzenga and her staff combed their collections for documents that relate to immigration, finding, among other things, a letter from a person who complained that there were Protestants proselytizing at Ellis Island. This prompted an inquiry and the establishment of a Catholic presence at the immigrant gateway.

The archives also have a Nov. 10, 1920, letter on immigration from Fr. John Burke, the first general secretary of the bishops’ conference, and it has much information surrounding the 1950 struggle over the anti-immigrant McCarran Internal Security Act. That struggle evidenced one of the first times there was a split within the Catholic organizational world, with the bishops supporting the law and Catholic Charities opposing it.

Students from different departments are invited to come to the archives. “We want to get them excited -- and able -- to use primary documents,” Mazzenga said. Her affiliation with the Institute for Policy Research & Catholic Studies brings her into contact with the full spectrum of departments at the school and the work of various professors. “It’s a fun job,” she said, smiling. “It’s a position where I try to educate people about all that we have.”

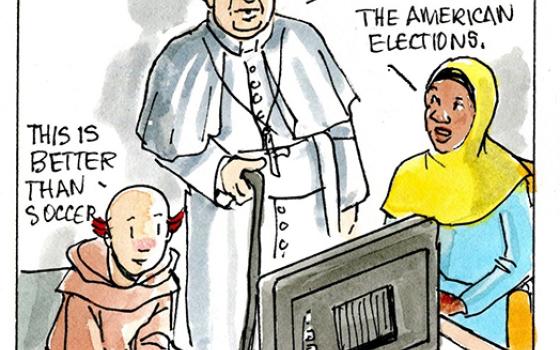

What really gets Mazzenga excited is when she discusses the various ways they are making the website user-friendly. The American Catholic History Classroom is clearly one of her favorite projects. With all the controversy over labor rights in Ohio and Wisconsin, it is fitting that the American Catholic History Classroom’s website highlighted the translation of a letter, dated Aug. 29, 1888, from Cardinal Giovanni Simeoni of the Vatican’s Propaganda Fide to Baltimore Cardinal James Gibbons, permitting Catholics to join the Knights of Labor. The website also features the famous 1964 “Pettigrew for President” series in Treasure Chest of Fun & Fact, in which the Catholic comics considered the possibility of electing a black man as president (NCR, Oct. 17, 2008). Indeed, Mazzenga is aiming to have all Treasure Chest comic books online. “They provide such an insight into popular culture in the ’40s and ’50s,” she noted. She also explains that the comic books were undertaken at the behest of the Commission on American Citizenship, which, in turn, had been urged on the U.S. bishops by Pope Pius XI, whose friendliness toward American democratic ways increased as he witnessed the growth of fascism and communism in Europe.

In addition to making archival material available online, Mazzenga also provides curriculum aids, such as questions related to particular documents. There are also “finding aids” on the website, giving historical notes on the collections so that teachers and students can easily access related materials. The website also helps teachers relate the materials to the National History Standards they must meet to sustain their accreditation. “We need to make it as easy as possible for teachers,” she said, and at a time when students think knowledge only comes via a laptop or iPad, the online resources are invaluable to overworked Catholic school teachers.

Mazzenga’s enthusiasm for archival research is contagious. Her face should be on posters for the “document-based learning” that has been emphasized in classrooms in the last 15 or 20 years, a development from the ’70s social history approach to research. But, in the end, it is not just enthusiasm that matters, it is content, and the archives over which Mazzenga presides are a treasure trove for anyone wanting to learn more about the history of the church in the U.S. Increasingly, much of that trove is just a click away.