Interfaith clergy prepare an altar in the desert to honor those who have died without names or identification in the desert in Santa Teresa, New Mexico. (KTSM/Jesus Baltazar)

"What did you go out into the desert to see?" (Matthew 11:7)

On a hot October afternoon, a group of volunteers, clergy and a few journalists gather in the desert in Santa Teresa, New Mexico, near a skull and other human remains. They lug chairs, carnations, candles and colored cloths to decorate a makeshift altar to memorialize migrants who've died and been abandoned here.

I join them as a volunteer with the Battalion Search and Rescue, a humanitarian group founded by Marine veteran James Holman, dedicated to searching remote and highly traveled desert areas for humans either in distress or deceased.

One Saturday per month, we scour a tiny piece of the southern New Mexico desert bordering El Paso, Texas, to the east and Mexico farther to the south. In the last three searches alone, we have discovered eight sites of skeletal remains.

Despite Battalion Search and Rescue's reporting these sites to local authorities, with precise GPS coordinates, months have passed and the remains and identification clues have not been properly claimed. Disheartened, Holman and his partner Abbey Carpenter decided to honor these unknown souls with our own memorial.

That is why, on this particular Saturday, friends and interfaith clergy have come to pray and honor the sacredness of the lives who have passed this way.

Franciscan Br. Maikel Gomez Perez kneels to pray and place a carnation by a skull left at a site of human remains in the desert in Santa Teresa, New Mexico. (KTSM/Jesus Baltazar)

It sounds like a daunting task. My search for those missing in the desert. And certainly not something I'd normally be doing on a Saturday morning. But I know it's a necessary task. And a humane one.

In the past year, the number of migrants dying in the desert has reached record proportions, particularly in the El Paso sector where I live. And more than 50% in our area are women. These high numbers are caused by the growing obstacles to entering the United States legally through a port of entry, creating dead ends that are forcing more people farther into the desert where even more danger lurks.

And sometimes death isn't the worst of it.

As news reports covering the Texas border all the way into Arizona would testify, most of the bodies remained uncovered or unidentified, and their whereabouts unknown to loved ones. That had been enough of a motivator for me to join the search and rescue organization in December 2023. It was something positive I could do. Something that would expose me to yet another piece of the journey of the asylum seekers I had accompanied in El Paso's houses of hospitality over the years.

Since I'm a Christian attempting to follow in the challenging, compassionate and at times completely crazy footsteps of Jesus, these desert searches inevitably involve reflection and self-examen. That's what this story of my experience entails.

Advertisement

On one of my first Saturday searches, I'd joined the faster-paced of two search teams, figuring I could easily walk the 8 miles we'd be assigned over the next several hours. My team of four spread out in horizontal formation, but my compadres were tall, long-legged men whose quick strides proved challenging for my short stature. Their neon orange sun hats rose high across my line of sight like burning flares marching in tandem.

I tried to keep pace, watching for the flicker of orange bobbing in and out of the corner of my eyes. Losing sight of my team could mean losing my way. The fact that we were all wearing walkie talkies attached to our backpacks didn't necessarily reassure me.

Even after eight years of living in this desert landscape, noticing the curvature of the land or identifying landmarks still escaped me. One rising hill of sand pretty much resembled another in my mind.

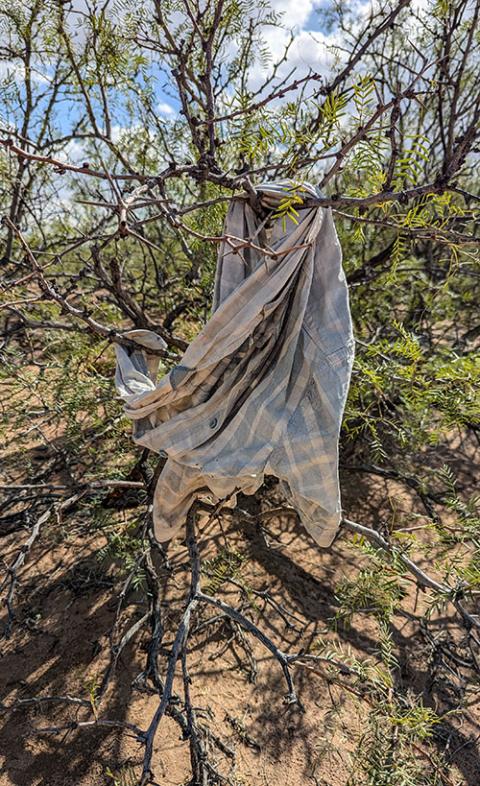

A woman's shirt dangles from the branch of a bush in the Santa Teresa Desert in southern New Mexico. (Pauline Hovey)

I've never been fond of the desert. My move here had been more about what I'd call "a holy lure" to serve at the southwestern border. An inner call that felt a lot like God messing with my heart. "You want to follow me," I'd heard Jesus say. "This is where you'll meet me."

As I struggled to keep my teammates within eyesight, I tried to pay close attention to my surroundings. It was necessary, not only to avoid the bristly brush and paper-thin pricklies protruding from cacti waiting to attack my legs and arms, but also to notice signs of the lives that had passed this way. An article of clothing that might provide someone's identification. A cellphone. A faded ID. Skeletal remains. The latter can be confused with glistening white stones or animal bones.

Soon, I spotted the telltale plastic bottles, emptied of water or electrolytes, strewn across the desert floor, the human footprints, some of them quite fresh, and the tossed-aside square pieces of foam and cardboard that migrants strap to their feet to hide their prints. Occasionally I'd come across a backpack, emptied of its original contents, filled with sand. Or a faded pair of jeans or jacket, discarded, half-buried, sun bleached and barely recognizable.

It struck me how those fleeing violence, hunger, persecution, economic devastation and other miseries I'll never know, must traverse across a desert to reach the promise of new life. The irony is, some made it thousands of miles, avoiding and encountering who knows what along the way, somehow shimmied over that border wall and landed on U.S. soil, only to die here, in the sand, several miles from the road and refuge.

Just like Moses and the Israelites. Their exodus, fraught with fear and uncertainty, on their way to the promised land. And just like the Israelites, they must surely wonder sometimes why God has brought them here to die.

A human femur and pair of pants covered in sand were discovered by the Battalion Search and Rescue in the Santa Teresa Desert in southern New Mexico. (Pauline Hovey)

As Christians, we're accustomed to hearing the story of Jesus being called into the desert, the fasting and purging that prepared him for his ministry. We're lured into the desert as a place of transformation, filled with opportunities to die little inner deaths and rely on God.

But no one needed to tell me that the things I've let go of during my 60-plus Lenten seasons were infinitesimal in comparison to what those who have passed this way have left. They have abandoned possessions and attachments, including children, family members, and their dignity.

No one chooses to journey into the desert unless they are seeking a spiritual encounter or are desperate for the promised land. And are willing to risk suffering for it.

Even as I peered through my polarized sunglasses over the glaring sand, searching for signs of human remains, I was aware of my minor preferences and discomforts. Like preferring to find a sliver of shade when we broke for lunch. Letting go of the discomfort of the sweat trickling down my back as my daypack pressed against me in the heat.

Feeling frustrated and humbled, I plunked my sun hat farther over my forehead and pressed on.

Personal items discarded by migrants are found by the search and rescue group not far from the road in the Santa Teresa Desert in southern New Mexico. (Pauline Hovey)

Suddenly, my walkie talkie crackled. Someone had found human skeletal remains. Two femurs. Ribs. We convened at the site where the bones lay spread out. Only a few feet away, a bra, panties, a small pair of jeans and a torn backpack appeared in the sand. We surmised the deceased was a woman, as were the majority we had encountered to date. Otherwise, nothing about this shortened life was recognizable.

Someone from the team tied strips of bright pink tape to nearby shrubs indicating the location for the local sheriff and Office of the Medical Investigator.

Although Holman would call to report these findings, we are losing hope that the authorities will respond. Human bones and other evidence we'd discovered nearly two months earlier still remained untouched at some sites. Was this indicative of an overloaded schedule or a disregard for these lives? We can only speculate.

As I gazed into the deceased woman's dirty, emptied backpack, I thought about the price the desert extracts for the promised land. For a privileged, contemplative spiritual seeker like me, it demands that I wake up. Not anesthetize myself to the Gospel message. The love-one-another message Jesus stressed again and again.

In Letters from the Desert, Carlo Carretto wrote about how he heard the depth of that message. "Leave everything and come with me into the desert. It is not your acts and deeds that I want; I want your prayer, your love."

Carlo gave up his comfortable life, joined the Little Brothers of Jesus and left Italy to venture off to the desert of Northern Africa, only to meet a poor man in need of a blanket and not give up one of the two he owned.

"What's the use of giving up everything and coming here to the desert and the heat, if only to resist love?" he asked, realizing he needed to love the life of others as much as his own.

His message reverberates across the sand. Maybe God brought me here to learn that lesson. How to die to the fear of giving up preferences and comforts, for the sake of the love of another. It's a small price to pay.