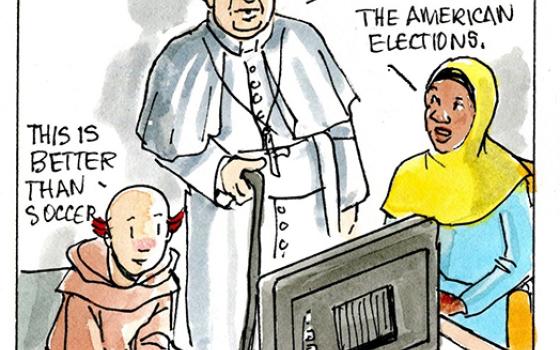

Dinner is served at Spectrum Youth and Family Services in Burlington, Vermont, in 2005. (Jerry Swope) *

I work with homeless, runaway and at-risk teenagers at Spectrum Youth and Family Services in Burlington, Vermont. Several years ago, a 19-year-old young man named Jackson showed up at our drop-in center for a hot meal. When we found out he was living in a car, we invited him into our shelter. Spectrum's mission is to serve as family for those youth who, for whatever reason, have none at that moment. And in my mind, a family does not let one of its own live in a car.

A few months later, one of our board members hosted a house party that some of our staff attended, and one of them brought Jackson along to say a few words. I listened to him speak about his life and about how grateful he was for the help he was receiving from us. I've worked with thousands of homeless young people over the last four decades, and Jackson stood out because of the kindness and sincerity that radiated from him.

He always had a job while with us, but what Jackson wanted more than anything else was to join the Marines. I didn't encourage him, nor did I discourage him. The military can be a good character-building experience for some people who have had a difficult life up until that point, but it can also be overwhelming for others.

Jackson applied, was accepted, and shipped out to boot camp in Parris Island, South Carolina.

Jackson wrote me, and it sounded like he was doing fine. When it was time for him to graduate from boot camp, I knew that none of his birth family would be there, so I asked one of our staff members to fly down and be with him at the ceremony.

Jackson phoned me the day of his graduation. He sounded thrilled. "We are so proud of you," I told him. "Congratulations!"

Things spiraled downward. Jackson transitioned on to the next phase of military training, and to this day I don't know what happened, but within a few weeks he was in trouble and then discharged. I called and called to get some sense of what was going on, but I couldn't reach him, and had no luck getting any information from the Marines.

Soon the staff in our drop-in center let me know that Jackson was back in Burlington and occasionally coming around for a meal. I told them, "Please have him contact me as soon as you see him again. Tell him he can come back and live with us if he wants to." But I didn't hear from him.

A month later, I was on my computer at home on a Saturday night and pulled up the online version of the Burlington Free Press to see what was going on that day. I saw a headline about a suicide. A young man had led police on a high-speed chase and then killed himself with a gun.

It was Jackson.

Advertisement

A few days later, a wake was held for him at a funeral home in the town where he had grown up. I went to it with several others from Spectrum. Our hearts ached.

There was an obituary in the paper, with the standard line to the effect of "He leaves behind the loving family of …" But a few days later, a woman phoned me who identified herself as having been a neighbor to Jackson and his family when he was growing up.

"That obituary was a lie," she said. "There was no loving family for Jackson. If he had a loving family at all, it was you people at Spectrum."

She told me that her son and Jackson had been close childhood friends, but for some reason the friendship ended. She didn't know why, but right before he entered the Marines, Jackson came to see her son, all these years later. He told her son that when they were little he had once stolen some Pokémon cards from him, and he now wanted to apologize.

She told me it spoke volumes about the kind of person Jackson was. I agreed.

When you come into our office at Spectrum today there are several group photos of young people on the wall by the entrance. Jackson is in one of them, having dinner with a bunch of the other kids in the house, a smile on his face. The staff member we flew down to Parris Island is gone, and only one other person besides me who works at Spectrum even remembers Jackson now. Everyone else employed here walks by that photo every day, not knowing the story behind that one young man's smile.

But I know who he is. He was a tender soul who, like many of the kids with whom we work, had endured great suffering early on in life. For some people, that kind of suffering results in a personality filled with bitterness. Jackson always revealed gratitude.

The definition of family means different things to different people. And as that woman who called me stated, we at Spectrum were Jackson's family, at least for a brief period. We are there for young people when they need us, in whatever way they need us. That's what a family is, that's what a family does. Jackson may not have had much happiness in his life, but at least for a short while, he was surrounded by people who cared about him and loved him. I believe he knew that, and my soul finds comfort in in his knowing.

[Mark Redmond is the author of The Goodness Within: Reaching out to Troubled Teens with Love and Compassion and the host of the podcast "So Shines a Good Deed."]

*The caption in the top picture has been corrected.

Editor's note: We can send you an email every time Soul Seeing is published so you don't miss it. Go to our sign-up page and select Soul Seeing.