Mourners participate in a peace march May 6, 2016, prior to the funeral Mass of Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan at the Church of St. Francis Xavier in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. Berrigan, a peace and social justice activist, died April 30, 2016, at age 94. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

A "biography and memoir" does double duty for any single author, though, overall, there is more biography in Jim Forest's new book than memoir. Indeed, when finished I knew more about Jesuit Fr. Dan Berrigan than I did about the author. And I already knew quite a bit about Berrigan. Memoir doesn't come from memory, but memorandum, the recording of important events, and Forest illuminates any number when both he and Berrigan overlap. But, as the photograph on its cover shows, this is Berrigan's book.

If anyone wants to read only one book on Dan Berrigan, At Play in the Lions' Den is it. And the reader will be getting many works at once: a history of the Catholic radicalism of the last 50 years, a digest of many books Berrigan himself wrote, a chronology of the social history of both the Catholic Church and the Jesuit order in America, among others. Overall, the volume amounts to a compendium, including helpful photographs and excerpts of other literature.

For nearly 50 years, the Berrigan name was most often plural. It was Dan and Phil, the Berrigans, ever since they both appeared in Catonsville, Maryland, in 1968, to burn draft files. That became the signature event of the new Catholic left protest movement of the period. The reasons are many: the success of the 1970 play Dan wrote about the trial, using the transcript as its base, the film that appeared not long after, the inherent symbolism in the tiny immolation the nine participants sparked, echoing the war they protested and their own religious motives. An exhaustive book titled The Catonsville Nine: A Story of Faith and Resistance in the Vietnam Era appeared in 2012.

It was hard to top, but many other actions followed. The 2013 documentary "Hit & Stay" is the most complete record of this sector of the anti-Vietnam War movement. It was a busy time. Forest, who himself was part of the Milwaukee 14, covers a good bit of this ground, but what is even more illuminating is his treatment of the Berrigans' childhood: Dan's years becoming a Jesuit, a long process, and the last 20 years of his life, quieted by both his own aging and the curdling of the culture. Berrigan's last protest appearance was at Zuccotti Park during the Occupy Wall Street moment in 2011. He was there, though he did not speak. (Forest quotes Joe Cosgrove: "Dan's witness could not have been louder.")

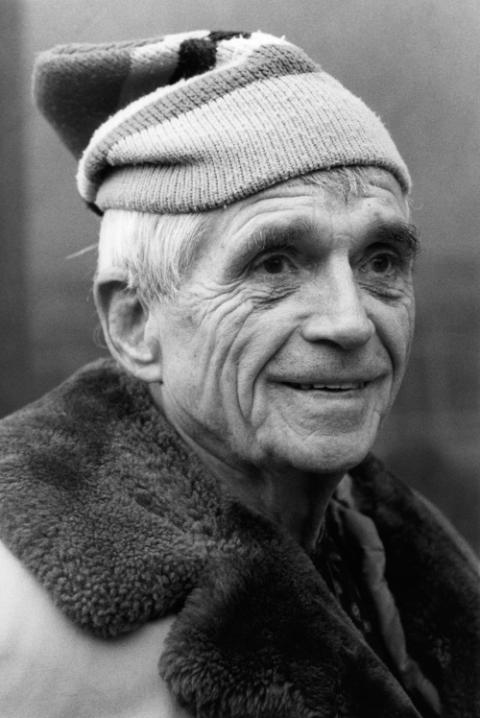

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS files)

In Philip's case, it was his stint in the Army. In Dan's case, it was the Jesuits, sending him to France, Czechoslovakia and South America as a young man. One of the great harms of Vietnam, the war that concentrated the Berrigans' fame, was that great widening and enlightenment didn't happen with the young generation of men who fought in it.

But speak Berrigan did, throughout his life. Previous to Catonsville, Dan, like any number of men of his generation, went from the most provincial of upbringing — poor family, an abusive father — to become a worldly figure. The so-called Greatest Generation was, most regrettably, great because World War II took so many ordinary Americans, plucked them from parochial back- grounds, and introduced them to the wide world.

Forest's book is consistently interesting for even those, like me, who know a lot about its subjects. It is his intimate side of the "memoir" parts, so we see Dan Berrigan as one of an extended family, as well as a number of his associates Forest shares, Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day in particular. Forest's portrait of Merton is especially revealing.

There were ups and downs throughout Dan and Phil Berrigan's careers as professional protesters. The largest down was the Harrisburg 7 trial, not an event they brought about. It was the product of J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI, which had turned a willing informer who shared a prison with Phil, and his love affair with Elizabeth McAlister, into a federal case. It was a large road bump in the Catholic left's progression and reputation.

Advertisement

Dan, himself, mostly free of collateral damage from the Harrisburg case (he was once charged as an unindicted co-conspirator), wandered into some unfortunate controversies, centering first in 1973 on Arabs and Israel. He, not to put too fine a point on it, attacked the Jews. Forest goes through this material carefully, though he doesn't dwell on a lot of unfortunate historical material relating to the early 20th-century Catholic Church. It was a no-win situation for Berrigan and, in this one case, he seemed to go off half-cocked, given his lack of familiarity with Israel at the time, which he corrected after the blowup. Given the natural allies of the antiwar left, this estrangement lessened his influence for a short time. (The current far left, for better or worse, now echoes most of his criticism.)

They had gained the moral high ground with the sui generis draft board raids, and Hoover sought to knock them off their pedestal. The smuggled and duplicated letters of Phil Berrigan and McAlister gave them all the ammunition required, and though the government prosecutors lost the case (hung jury on major counts, convictions of McAlister and Berrigan on minor counts that were later voided), Hoover's intention was achieved. The Berrigans' group splintered, reformed as Jonah House in Baltimore, and anti-nuclear weapons became the protesters' focus for the remainder of their years.

The second bump was a clear-cut and vocal anti-abortion stance, just as second-wave feminism was rising. Again, to left political coalitions, there continues to be the sour equation: Pro-life = President Donald Trump.

The sibling rivalry between Phil and Dan, often commented on, seemed in later life to turn on Phil's marriage to McAlister. Dan, alone, knew of the alliance before the news came out during preparation for the Harrisburg trial, but he was never able to entirely square it with his deeply held affections for his brother. Forest quotes a letter from Dan to Phil: "I had of course in no way been prepared for this. How could I be?" It remained a betrayal, however mysterious its reasons, to Dan, not wholly understandable, since it was so far from Dan's loyalty to his Jesuit vows.

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, right, and actor Martin Sheen, third from right, join the annual School of the Americas protest in 1999 at Fort Benning, Ga. (CNS/Quirin, The Messenger)

It was a betrayal to a lot of people in the now old new Catholic left. But among the many charms of Forest's valuable book are the photographs that abound in the margins. And on Page 219 the reader will see one of Phil Berrigan and Liz McAlister and two of their young children. Both the adults look so happy.

[William O'Rourke is professor emeritus of English at the University of Notre Dame. In 2012, an updated edition appeared of his 1972 book, The Harrisburg 7 and the New Catholic Left.]