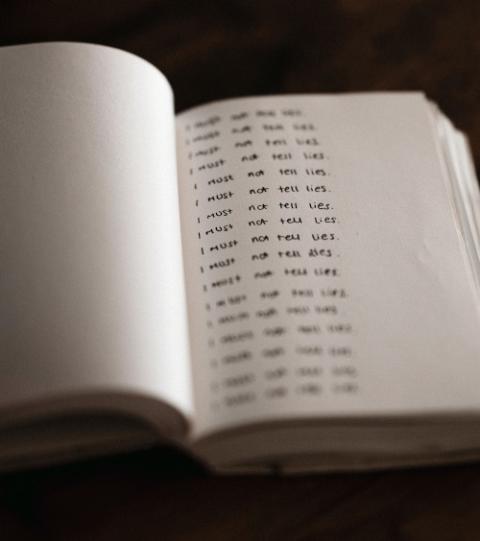

(Unsplash/Kristina Flour)

How bad should you feel if you share a Facebook post or tweet that turns out to be untrue?

Well, you could listen to the advice of Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg or Twitter founder Jack Dorsey. Or you could listen to a few other innovators with impressive numbers of followers:

"I tell you," said Jesus, according to the Gospel of Matthew, "on the day of judgment people will give account for every careless word they speak."

"Does anything topple people headlong into Hellfire, more than the harvests of their tongues?" asked Muhammad.

The Buddha emphasized the importance of "right speech," defined as "abstaining from lying, from divisive speech, from abusive speech, and from idle chatter."

Advertisement

The great religious traditions do not stop at the simple Sunday-school warning against lying. They dive deep into our unconscious motivations, call out our intellectual laziness and suggest that we have an affirmative moral obligation to be fact-checkers.

In our internet age, this ancient wisdom is urgently relevant. The spread of misinformation is one of the most serious problems our society faces. Misinformation advances bad medical information and more mortality; it undermines democracy, turns people against one another and makes it harder for people to discern the truth.

And it's getting worse: The popularity of Facebook posts from fake sources has tripled since 2016. And on Twitter, lies spread six times faster than truth.

Academic and government groups have proposed solutions, from regulating Facebook to strengthening libraries. But one part of the problem that rarely gets discussed is our own personal responsibility.

Many of us are complicit. The top 100 fake stories in 2019 were viewed a staggering 150 million times.

Many of us are complicit. The top 100 fake stories in 2019 were viewed a staggering 150 million times.

The sheer numbers suggest that social media falsehoods are shared by well-meaning people. Most of those who spread misinformation likely believe they are being righteous. Why do bad retweets come from good people?

Some spread misinformation because the statements validate their own worldview, which assumes that the other side is vile: President Joe Biden is creating "quarantine camps," according to one story with thousands of shares, and he was endorsed by antifa. Another widely shared piece: "NYC coroner who declared the death of Jeffrey Epstein a suicide made half a million dollars a year working for the Clinton Foundation until 2015."

Other readers shared a manipulated photo purporting to show that Donald Trump pooped in his pants while playing golf, and another claiming that police had set fire to teepees at the Standing Rock reservation.

In a remarkable message on "fake news and journalism for peace," Pope Francis declared that the "tragedy of disinformation is that it discredits others, presenting them as enemies, to the point of demonizing them."

"The best antidotes to falsehoods are not strategies," the pope continued, "but people: people who are not greedy but ready to listen, people who make the effort to engage in sincere dialogue so that the truth can emerge; people who are attracted by goodness and take responsibility for how they use language."

(Unsplash/Annie Spratt)

While many of us do not deliberately share information we know to be false, we also don't try very hard to discern fact from fiction. One study showed that those most likely to accidentally spread misinformation tended to have low levels of what social scientists call "conscientiousness." Another found that sharing misinformation comes more from "inattention" than to ideology.

The major religions view these unconscientious choices as consequential.

The Quran urges us to do the hard work of self-awareness: "If a wicked person comes to you with any news, ascertain the truth, lest you harm people unwittingly, and afterwards become full of repentance for what you have done."

Allah, in short, wants us to be smarter information consumers. "Why do not the believing men and women, whenever such (a rumor) is heard, think the best of one another and say, 'This is an obvious falsehood'? ... When you take it up with your tongues, uttering with your mouths something of which you have no knowledge, you deem it a light matter. Whereas in the sight of God it is an awful thing!"

Being self-aware about one's own culpability is hard — which is why several sacred texts tackle it so directly. "The simple believe anything," says Proverbs, "but the prudent give thought to their steps."

The Apostle Paul warns in his Letter to Timothy that some will have "itching ears" and "will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own passions, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander off into myths."

Today's spiritual teachers also need to emphasize that what we click on and pass along is as important as what we say.

The Buddha laid out 10 criteria to help discern the truth. Several would be relevant for the modern web surfer. He suggests that we not rely on:

1) unconfirmed reports, repeated hearing,

2) legends, rumor, hearsay,

5) logical reasoning, conjecture, surmise,

6) inference, an axiom,

7) analogies, reflection on superficial, specious appearances

He urged us to question whether one's own beliefs are driven in part by "greed, hatred and delusion" and use personal knowledge "through the eye or the ear."

In practice, this means we need to discern not only between fact and fiction, but among news sources. Studies have shown that falsehoods are more likely to be spread by those who distrust all news media. Once we believe that all sources are equal (i.e., equally untrustworthy), truth will not stand much chance. We need to do the work to find news outlets that invest in intellectual honesty and fact-checking.

Today's spiritual teachers also need to emphasize that what we click on and pass along is as important as what we say. Preachers who sermonize about abortion, racism or other serious moral questions should also inveigh against the spiritual risks of retweeting.

On Yom Kippur, Jews should apologize for forwarding the Facebook post saying 75% of Atlanta's police force had resigned. At confession, Catholics should ask forgiveness for sharing the fake tweet about a Trump pee-pee tape (not to mention the ones claiming that Francis endorsed Trump … and Bernie Sanders). Bible classes that teach kids to follow The Truth should advise them how to discern the truth.

What about the people who knowingly spread misinformation?

Many do so in order to harm the other team. Others may view it as a victimless crime. Perhaps we should go a bit more Old Testament on them. In addition to labeling false information, perhaps social media platforms should publish the names of those who share the most misinformation, alongside a big scarlet "M."

But mostly we need to understand that these split-second, seemingly inconsequential choices have moral gravity. If we're not sure whether something is true, we shouldn't share it. Slow down. Evidence is growing that merely causing people to pause reduces the spread of misinformation.

Err on the side of being fiercely discerning, even if it means being unsocial. We can certainly keep blaming Zuckerberg too, but next time we log in, we should remember the log in our own eyes.

Prompted by his anguish over the spread of misinformation, Francis recently created a new version of the famous prayer of St. Francis:

Lord, make us instruments of your peace.

Help us to recognize the evil latent in a communication that does not build communion.

Help us to remove the venom from our judgments.

Help us to speak about others as our brothers and sisters.

You are faithful and trustworthy; may our words be seeds of goodness for the world:

where there is shouting, let us practice listening;

where there is confusion, let us inspire harmony;

where there is ambiguity, let us bring clarity;

where there is exclusion, let us offer solidarity;

where there is sensationalism, let us use sobriety;

where there is superficiality, let us raise real questions;

where there is prejudice, let us awaken trust;

where there is hostility, let us bring respect;

where there is falsehood, let us bring truth.

Amen.