Natural family planning paraphernalia, circa 1983 (NCR photo/Arthur Jones)

On July 29, 1968, Pope Paul VI published his encyclical on the regulation of birth, introducing what we call here the Humanae Vitae affair. Now approaching its golden jubilee, the encyclical was published at a time of twofold crisis, one theological, the other cultural. Paul's theological teaching, "each and every marital act must of necessity retain its intrinsic relationship to the procreation of human life" (11), had never been taught before in the Catholic tradition and further fueled the post-Vatican II theological wars in the church. Humanae Vitae ("Of Human Life") itself further fueled the post-World War II culture wars over the meaning of sexuality. The scars from both these wars are still evident. They have inserted themselves into the papacy of Pope Francis, oblivious to the fact that he has moved away from the Catholic obsession with sex and birth control toward the beauty of a virtuous, just and loving marriage. His focus is on the complexity of human experience and relationships, which Humanae Vitae failed to adequately consider.

Experience as a source of ethical knowledge

Catholic theological ethics accepts a quadrilateral of sources of ethical knowledge, the so-called Wesleyan Quadrilateral: Scripture, tradition, reason and experience. Any Catholic moral theology seeking to be normative has to prioritize, interpret and coordinate these four sources into a comprehensible moral theory. In this essay, given space restrictions, we focus on only one element in the quadrilateral, namely, human experience, which Gaudium et Spes lauds as opening "new roads to truth" (44). The Catholic natural law tradition has always taught the relevance of experience for formulating ethical criteria to judge the rightness or wrongness of an act. To deny that relevance is to embrace a reductionist methodology in which the only legitimate human experience is that which conforms to, and confirms, already established doctrinal norms. It was such a methodology that allowed the magisterium's approbation of slavery until Pope Leo XIII's rejection of it in 1890, and the denial of religious freedom until the Second Vatican Council's approbation of it in 1965. We argue that a sustained reflection on, and integration of, human experience into Catholic ethical method will lead to the revision of some absolute sexual norms, among them the norm prohibiting artificial contraception. We must first define what we mean by experience and explain its role in reaching normative conclusions.

Human experience defined

The experience we speak of in this essay is well-defined by George Schner as "active participation in specific events … the undergoing of life and the accumulation of knowledge thereby." We hasten to underscore that human experience is never a standalone source of theological ethics, and that "my experience" alone is never a source at all. Ethical authority is granted only to "our experience," to communal experience in constructive conversation with the three other sources of ethical theology. Such experience, as actively participated in and consciously apprehended by humans is never neutral, unadulterated experience. It is always experience construed by the interpretation of individuals and communities in specific socio-historical contexts. It may, therefore, be differently construed by "me," by "us" and by "them."

In a church that is a communion of believers, the resolution of different construals of experience to attain ethical truth requires, we suggest, the honest and respectful dialogue of charity lauded by Pope John Paul II. Such dialogue, we are convinced, will reveal patterns of experiential meaning and value that are shaped by the Christian tradition but are not yet fully integrated into that tradition. We inquire here about patterns of tradition-shaped meaning that are reflected in the lived experiences of married couples who, for ethically legitimate reasons, use contraceptives to regulate fertility and practice responsible parenthood. But, first, an important caveat.

A common misuse of human experience and statistical analysis is to confuse causation and correlation. Causation results from a cause and effect relationship between two variables; it can be determined only by research that strictly controls for all the experiential variables that could be possible causes of the effect. Correlation, on the other hand, is easily determined by observation and claims only that one variable follows another. Confusing correlation and causation leads to inaccurate conclusions and the citing of false "evidence" to support a position.

We find correlation posing as causation in Humanae Vitae's defense of its teaching against contraception. It notes that people need to consider "how easily this course of action [artificial contraception] could open wide the way for marital infidelity and a general lowering of moral standards." What is the relationship between contraception and marital infidelity? Does contraception cause infidelity or is there merely a correlation between them? No causal relationship between contraception and infidelity has ever been demonstrated, and so we ask, is there any correlation between them that suggests an ethical norm on contraception? Or is there any correlation that militates against Humanae Vitae's teaching, especially within a just, responsible and loving marital relationship?

Humanae Vitae's apologists sometimes confuse causation and correlation when citing data to defend its teaching. In their defense of natural family planning or NFP, the only ethically acceptable form of birth control in Catholic teaching, Jesuit Frs. Kevin Flannery and Joseph Koterski adduce a causal connection between Catholic sexual teaching and marital stability: "Every study shows," they assert, without referencing a single study, "that marriage goes better for couples who practice what the church teaches about sexuality. Their divorce rate is less than 5 percent while the rate for Catholic couples in general is over 40 percent." This is a too-sweeping assertion that makes no mention of other variables known to contribute to marital stability and makes no effort to isolate any valid causal relationship. After some spouses used NFP, their marriages were found to be stable; therefore, NFP caused their marriages to be stable. It takes a study much more statistically sophisticated than any they cite to establish a causal relationship.

There are many other variables statistically demonstrated to be correlated with marital stability: having parents who have not divorced, level of education, mature age at marriage, level of religiosity, to name only a few. These variables would have to be all factored with NFP and all of them would have to be carefully controlled in relation to each other before any valid conclusion about causation could be made. It is much more likely that there is no more than correlation between marital stability and NFP, and that already convinced observers have jumped to a preferred but false conclusion. Census studies at the time of Humanae Vitae's publication indicate a lowered divorce rate for those who attend church regularly and an even lower divorce rate for those who both attend church and pray privately at home. It might be that church attendance and prayer life are more directly related to marital stability than NFP.

Cultural experience and contraception

One type of experience that provides a basis for reflection leading to the formulation of ethical norms is cultural experience. Gaudium et Spes teaches that thanks to "the experience of past ages … and the treasures hidden in the various forms of human culture … the nature of man himself is more clearly revealed and new roads to truth are opened." It adds that "from the beginning of [the church's] history, she has learned to express the message of Christ with the help of the ideas and terminology of various philosophers" (44). It is true that the church is called on occasion to be countercultural, to confront cultural theories and actions that do not lead to human flourishing, for example, the rabid individualism rampant in United States culture. It is equally true that reflection on cultural experience has led and can continue to lead to insight into ethical truth and the communication of that truth from that culture to others. The pastoral letters of the U.S. bishops' conference on the economy and nuclear war are examples of the dialectic between culture and the development of ethical norms. The letters draw on the traditional Catholic principles of justice and fairness, and articulate them in light of the specific cultural experience to which they respond.

There is a serious disconnect between the universal teaching prohibiting artificial contraception and particular cultural experiences. We briefly explore two of those issues. The bishops of Canada note the following in their statement preceding the 1994 U.N. Conference on Population and Development in Cairo: "We are convinced that unchecked growth in population is a function of poverty." There is substantial evidence indicating a strong correlation, if not a cause, in developing countries between population growth and extreme poverty leading to disease and early death. There is also evidence that family planning policies that include the use of contraceptives have reduced this unchecked growth in many developing countries by more than half. People in these countries are least able to provide adequate nutrition, care and basic needs for children born into poverty, and it is arguable that not using artificial birth control in these countries is irresponsible and is contra-life. More than 20,000 people die every day because of extreme poverty. Artificial contraception could enable for them the good of life, such an important value in African culture, not attack it as some traditionalist theologians claim.

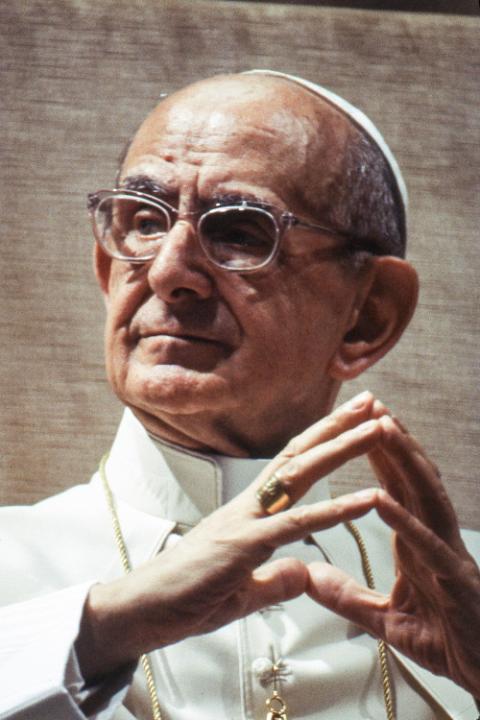

Pope Paul VI (CNS/Catholic Press/Giancarlo Giuliani)

Given the strong directional correlation between fertility and poverty, the Canadian bishops' proposal seems eminently reasonable and reflects the principle of responsible parenthood: "We recognize that a couple's responsibility to decide the number and spacing of their children must take into account a number of factors: the family's own limits in regards to health as well as their material resources; the demographic reality of the country where the couple lives, and also the world's demographic context. This discernment will be based on the couple's own ethical and religious convictions, as well as the moral implications of the family planning methods being considered." This method of allowing human experience to inform, if not the formulation of the ethical norm guiding marital fertility, at least its application is in stark contrast to the universalist, acultural, ethical method grounding the absolute norm prohibiting contraception in Humanae Vitae.

There is a second disconnect between the Catholic teaching prohibiting artificial contraception and diverse cultural contexts. The church's only approved method of birth regulation, NFP, presumes "mutual love and decision making" between the spouses within the marital relationship. This is a splendid ideal for a marital relationship, but it does not reflect the cultural and relational reality of couples throughout the world whose relationships exist within, and are shaped by, patriarchal cultures. In these cultures, the husband is the unquestioned authority in the marriage, and the fundamental equality required to practice NFP is absent. In these experiential contexts, it can be oppressive for the church to prescribe an approach to regulating birth that is countercultural and creates an undue burden for women. Given the varied cultural and experiential contexts of marital relationships throughout the world, neither social nor sexual norms can be "one size fits all." Responsible parenthood must be adapted to specific cultural contexts. It is irresponsible and oppressive to teach an absolute ethical norm that can actually damage human dignity within marital relationships, especially the dignity of women.

Scientific experience and contraception

Another facet of human experience is scientific experience. New discoveries and new technologies challenge traditional ethical answers based on inaccurate or incomplete scientific knowledge and raise new ethical questions that require new answers. Some answers will be drawn from traditional ethical principles, but in a new, nuanced way that may lead to the revision of an ethical norm. Recent papacies have consistently taught the need to integrate the discoveries of the human sciences in formulating ethical truth, but they have also been selective in actualizing that teaching. This selectivity is exemplified in three distinct ways: first, when the magisterium ignores what the sciences have to contribute to the discernment of ethical truth when such a contribution would challenge a pre-established norm; second, when it allows science, defined in a narrowly biological sense, to disproportionately inform norms; third, when it misrepresents or falsifies scientific evidence. We consider each case in turn.

First, in the case of fertility rates and poverty, the logical implications of science are not always embraced and allowed to transform the established ethical norm on contraception. Scientific studies indicating the correlation between high fertility rates, poverty and early death, and the strength and directionality of this correlation, were not as numerous in 1968. As this data has become more readily accessible and recognized by the magisterium, we would expect it to be incorporated into the reformulation of the church's ethical norms. In the case of the norm prohibiting contraception as a means for facilitating responsible and safe parenthood, however, scientific insights seem to be ignored.

Advertisement

Second, a major concern the church's official teaching on contraception does not adequately consider is the reality of HIV/AIDS, especially in Africa. Ignoring the common African tradition of the importance of life, not only individual but also communal life, it continues to discourage the use of condoms to prevent HIV, thereby threatening that so-important human and communal life. The late Cardinal Alfonso López Trujillo, president of the Pontifical Council for the Family, claimed publicly that the HIV virus can penetrate a condom and that promoting condom use leads to sexual promiscuity. The first claim is blatantly false; when used properly, latex condoms do prevent the spread of the HIV virus. The second claim elevates what is no more than a correlation to a causal relationship, though there is no scientifically demonstrated causal connection between contraception and sexual promiscuity. Condom use alone is never going to be the solution to the AIDS crisis; it does not respond to the root of the crisis. It can, however, within the established Catholic ethical tradition, serve as one way to contain its spread. The context is one in which thousands of human lives hang in the balance.

Third, there is an already-established magisterial approval for the use of artificial contraception to treat a female physical disease. If contraception can be used to treat a woman's physical disease, why can it not also be used to treat the affective strain an unplanned pregnancy places on women at the prospect of a child being born into poverty and early death? Why can it not be used to prevent the spread of AIDS among women for whom, for physical, cultural or familial reasons, the use of NFP is not possible? Women account for some 50 percent of AIDS infection throughout the world and for some 60 percent of new infections in sub-Saharan Africa. The refusal to adequately address this issue through a revised moral norm results from the type of reasoning that ignores experience and has warranted the accusation of physicalism against magisterial teaching.

A critic of Pope Paul's encyclical banning contraception draws an overflow crowd of 9,000 at a meeting held during the annual Catholic Day Congress at Essen, West Germany, in 1968. (RNS)

Theological experience and contraception

There is a third type of experience that unites theology and human experience and provides insight into the teaching on contraception. Theological experience describes here the interconnected theological realities known as sensus fidei and reception. Sensus fidei is a theological concept that denotes both the instinctive capacity of believers to recognize the truth toward which the Spirit of God is leading them and their spontaneous judgment that such truth has theological weight. Sensus fidei is a charism of discernment, possessed by the whole church, laity, theologians and bishops together, which knows and receives a teaching as truth and, therefore, to be believed (see Lumen Gentium, 12). It derives from the lived experience of Catholic believers and the accumulation of experiential knowledge.

Reception is an ecclesial process by which virtually the whole church assents to a teaching, thereby assimilating it into the life of the whole church. Reception does not make the teaching true. It is, rather, a prudential judgment from experiential data that the teaching is good for the whole church and is in agreement with the apostolic tradition on which the church is built. It is important to be clear that reception is a judgment, not about the truth of a teaching but about its usefulness in the life of the church. A non-received teaching is not necessarily false; it is simply judged by virtually all believers to be irrelevant to both their own lives and the life of the church. As culture, time and place inevitably enculturated the good news of what God has done in Jesus the Christ, so, too, do they also enculturate every ethical teaching and every reception of that teaching. The act of reception, however, cannot and does not receive the tradition of the past unchanged; the past is always re-received in the cultures of the present. There are many examples in Catholic history of both reception and non-reception.

The social sciences provide substantial evidence of non-reception of the magisterial teaching on contraception among the faithful, theologians, and many bishops and clergy both at the time Humanae Vitae was promulgated and in its aftermath. The vast majority of Catholic couples worldwide, some 85 percent of them in a recent Univision survey, use a form of contraception prohibited by Catholic teaching. This use reflects radically changed attitudes toward contraception over the last 50 years. In 1963, over 50 percent of American Catholics accepted church teaching on contraception; in 1987, that number dropped to 18 percent; in 1993, it dropped further to only 13 percent. This overwhelming non-reception indicates that the universal sensus fidei does not assent to the church's teaching on contraception. Surveys indicate further that the majority of Catholics now look to themselves rather than to church leaders as the proper locus of ethical authority on contraception and other sexual issues. Sadly, the magisterium's loss of credibility, due to not only its absolute stance on sexual norms, but also its toleration of widespread clerical sexual abuse, has effectively obscured the real content of Humanae Vitae, which is a beautiful reflection on conjugal love and the unitive meaning of sexual intercourse.

Its non-reception by Catholic faithful does not prove that the church's teaching on contraception is false. It proves only that it is irrelevant to the vast majority of married couples and their theological experience. Jesuit Bernard Lonergan's commentary immediately following the publication of Humanae Vitae in 1968 remains apposite today. He pointed out the biologically obvious, namely, that the connection between sexual intercourse and conception "is not the relation of a per se cause to a per se effect" but rather "a statistical relationship relating a sufficiently long and random series of inseminations with some conceptions." He goes on to assert that "marital intercourse of itself is an expression and sustainer of love with only a statistical relationship to conception." While there is not always a conception following sexual intercourse, there is always between loving spouses a causal relationship between intercourse and conjugal love. That is enough to argue for not only the separability, but also the natural separation of what the magisterium calls the procreative and unitive meanings of the conjugal act. Phrases like "each and every marital act must of necessity retain its intrinsic relationship to the procreation of human life" (Humanae Vitae, 11), Lonergan argues, make no sense. They derive from the old, discredited Aristotelian biology and not from modern biology. The issue, we argue, is not whether or not people have to have reasons for accepting Paul VI's decision on contraception. The issue is that, when there is no valid reason for accepting his precept, that precept ought never to be an ethical norm. We further argue that 50 years of Humanae Vitae's growing non-reception is a more than sufficient reason to consider a revision of its contraceptive norm.

Pope Francis and contraception

Does Pope Francis has anything to contribute to this discussion? He suggests an answer in two places in his apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia. First, he notes that "the development of bio-technology has also had a major influence on the birth rate." He strongly condemns "forced State intervention in favor of contraception, sterilization, and even abortion," and strongly affirms "the upright consciences of spouses who … for sufficiently serious reasons … limit the number of their children" (42). Second, he embraces the Second Vatican Council's strong statement on the authority and inviolability of conscience (Dignitatis Humanae, 3) and declares that, while Paul VI's Humanae Vitae and John Paul II's Familiaris Consortio "ought to be taken up anew" and " 'the use of methods based on the laws of nature and the incidence of fertility' (Humanae Vitae, 11) are to be promoted," it is " 'the parents themselves and no one else [who] should ultimately make this judgment in the sight of God' " (Amoris Laetitia 222, quoting Gaudium et Spes, 50).

Pope Francis greets retired Pope Benedict XVI at the beatification Mass of Blessed Paul VI in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Oct. 19, 2014. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Francis complains that we "find it hard to make room for the consciences of the faithful, who very often respond as best they can to the Gospel amid their limitations, and are capable of carrying out their own discernment in complex situations," adding the trenchant judgment that "we have been called to form consciences, not to replace them" (37). He declares that "individual conscience needs to be better incorporated into the Church's praxis in certain situations which do not objectively embody our understanding of marriage," for conscience "can also recognize with sincerity and honesty what for now is the most generous response which can be given to God, and come to see with a certain moral security that it is what God himself is asking amid the concrete complexity of one's limits, while not yet fully the objective ideal" (303). He is speaking in this latter passage about divorce and remarriage without annulment, but he is articulating a traditional Catholic principle that applies to all moral judgments, including the judgment about whether to use or not to use artificial contraception: Circumstances and context are factors in every ethical judgment. The church has no comprehensive competence, and therefore no unquestionable authority, for evaluating human experience. It must then fall back on conscientious human judgments and the human sciences.

In conclusion, the affair Humanae Vitae introduced into the Catholic marital, ethical tradition in 1968 that "each and every marital act must of necessity retain its intrinsic relationship to the procreation of human life," has ended in 2018 with the conscientious and clear judgment of the people of God, instructed and validated by Pope Francis. The theological and cultural warriors can sheath their swords.

This essay is adapted from a journal article "Experience and Moral Theology: Reflections on Humanae Vitae forty years later," INTAMS Review 14 (2008).

[Todd A. Salzman is the Amelia and Emil Graff Professor of Catholic Theology at Creighton University. Michael G. Lawler is the emeritus Amelia and Emil Graff Professor of Catholic Theology at Creighton University. They are the co-authors of The Sexual Person (Georgetown University Press).]