(Unsplash/Roel Dierckens)

"I'm so bored."

"I hate feeling so alone."

"I'm just a burden."

My students shared how hard it was to persevere through this spring semester, nearly derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic. My heart grew heavy hearing their stories, especially as mental illness took its toll on my students' well-being.

Now, as we begin a new school year, we face the challenges of coping with and preventing the spread of the virus as well as how to effectively engage young people if we're not cultivating rapport, respect and co-responsibility together in the classroom.

While matters of public health and academic quality are undoubtedly critical, I wonder if we're spending enough time improving our response to the mental health needs of our students. Competing for our attention amid concerns about student retention, revenue loss and pedagogical efficiency is a mental health crisis that has been simmering for years and is now threatening to boil over.

In her book iGen, psychologist Jean Twenge describes a "sudden, cataclysmic shift downward in life satisfaction" among young people. She warns this is "only the tip of the iceberg" when it comes to a mental health crisis made worse by screens that leave many young adults feeling more anxious, depressed and lonely.

As studies continue to show causative links between time spent using social media and higher rates of mental distress and social isolation, we have to find a way to interrupt the cycle of dependence on digital tools, which is especially challenging during stay-at-home orders and remote learning.

Advertisement

Reports like this one from the Council on Foreign Relations show that COVID-19 lockdowns have resulted in increased incidents of domestic violence and child abuse in many homes. There is preliminary evidence to suggest mental health is also worsening. Being sent home from school and work, displaced from places that give us a sense of meaning and purpose, disconnected from friends and colleagues, and wrestling with demoralizing questions about employment, risks of illness and death, access to health care and looming financial uncertainty have produced immense pressure, fatigue and fear.

This heightened level of stress burdens the mind and body with an extra "allostatic load" — putting us on high alert, making it harder to get restful sleep, training us to be overly sensitive to external stimuli, imposing intrusive thoughts, and increasing feelings of numbness, detachment, depression, reluctance to contemplate the future and a higher likelihood of abusing alcohol and drugs.

Because people of color and those with lower economic security face discrimination and deprivation in access to healthcare, their allostatic load is even higher, causing even poorer mental health and compounding comorbidities, one reason for the disproportionately high numbers of illness and death in communities of color due to COVID-19.

The need to access safe and supportive spaces, consistent and nutritious meals, as well as resources to cope with physical, emotional and sexual abuse are some reasons why the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that school-age-children return to classrooms this fall.

I am not arguing for in-person education in the fall. In the absence of a vaccine and without guarantees about universal compliance to wearing masks, maintaining physical distancing and other safety measures, students, staff, faculty, administrators and our friends and family will be at risk not only of contracting the virus, but also long-term health effects including damage to the lungs, heart, brain and immune system.

(Unsplash/Finn)

The essential question we need to ask ourselves as educators and members of Catholic institutions is how can we best encounter, accompany and empower our students in the midst of this crisis?

While it is true that lockdown and physical distancing have given us more time for solitude and silence, and some people have used this time for spiritual growth, self-care and being more intentional about their attachments in and beyond the home, others have been harried by trying to balance the demands of work and family at the same time and in the same space.

For many, extra family time has been a boon and blessing. For others, it has exposed old wounds and inflicted new ones. Our task is to tend to these wounds and seek new strategies for healing and prevention. This requires a collective effort spanning individuals and institutions oriented toward mercy, generosity and solidarity.

This requires much more than getting students to "mask up" or stay a safe distance apart; it also means being more attentive and responsive to our mental and emotional needs. We respond to and are shaped by our environments — so if we teach in person, the extra spacing and layers of protection will make it harder to build a shared sense of rapport, respect and co-responsibility.

It is no small task to get to know people and build a sense of trust when half our faces are covered. If some students are present and others are tuning in through a screen, it will be even more difficult to cultivate the vulnerability and authenticity necessary for sharing honest reflections, tentative claims, clarifying questions, bold analysis and creative ideas for application.

If our only connection is through a screen, it is impossible see each other as whole persons, read body language (since a good deal of communication is nonverbal), respond spontaneously, and feel enough safety and trust to push the boundaries of our insights, inquiry and imagination.

Even while we rely on digital technologies to connect us, they are in many cases an impoverished if not exhausting experience of what it means to be human. And too many of us remain inattentive to the moral impact of spending so much time with our screens.

True, there are apps that can help us create consistent habits for self-care and mental health. FaceTime and Zoom can be helpful for connecting with others across distance, also serving as tools to facilitate regular check-ins with trained experts and peer mentoring programs. Surely many schools have created lists of available resources for students to access, but this assumes students will take the initiative to seek out assistance.

When we leave matters to individual choice to opt in or opt out, too many people get left out. If a student feels embarrassed or like an odd outlier — or even worse, a burden or a failure — he or she may suffer alone rather than reach out.

Formation happens more through relationships than individual dispositions or actions; we are what we repeatedly do together. For this reason, we have to be intentional about integrating self-care and mental health into our relationships as families, friends and communities for work, school or worship.

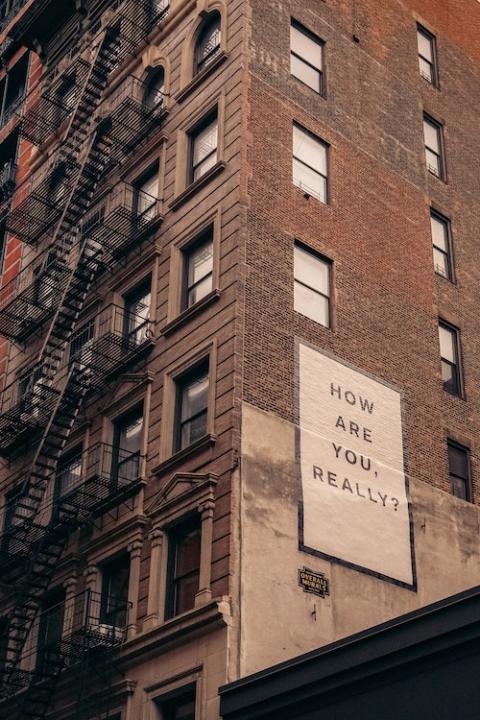

By leveraging existing networks as communities of practice, we can show that mental health is a priority by how we talk about mental health (as essential to everyone's health and wellbeing, not just an issue for those with a mental health condition), how we order our day (making time for prayer, reflection or meditation) and how we check in with each other (beyond "How are you?" and the trite "busy" or "fine" responses).

These are first steps toward building a culture of holistic health and well-being.

Beyond the personal and interpersonal levels, our institutions have to help us balance the demands of work and family life. Our government issued half a trillion dollars in aid to U.S. corporations but has yet to provide enough financial support to high schools and colleges trying to recover lost revenue from the spring, much less deal with whatever happens this fall.

Education is less about accessing knowledge than a process of reflection, analysis and application of learning in self-actualization. This happens through encountering texts and other learners, being in conversation together and developing relationships that make us more fully human.

Regardless of if or for how long we can open schools for in-person education, we will have to find new ways to relate through a screen so that our time together communicates not just support or accountability but an unceasing reminder to each and all: You matter, you belong and you are never a burden.

More than providing access to resources, we will have to be partners in creating campus cultures that welcome, affirm and empower.

[Marcus Mescher is associate professor of Christian ethics at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. He specializes in Catholic social teaching and moral formation. His first book, The Ethics of Encounter: Christian Neighbor Love as a Practice of Solidarity, was published earlier this year by Orbis.]