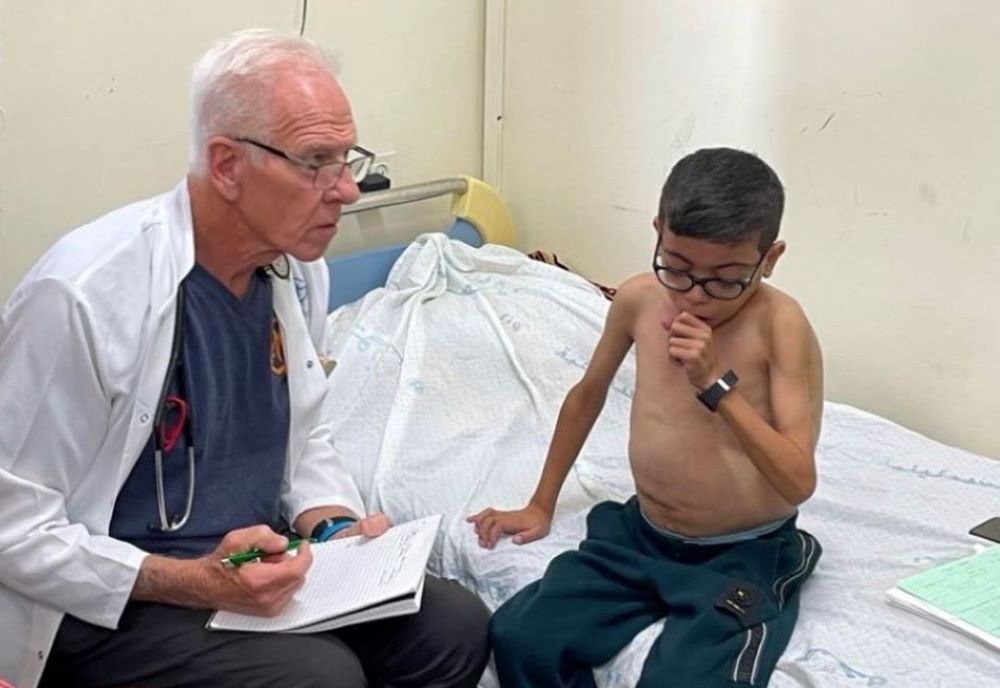

Dr. Greg Shay, a retired pediatric pulmonologist who lives in San Francisco, interacts with a patient with cystic fibrosis and malnutrition at Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis, Gaza, in October. Shay has made three medical missions to Gaza since 2022. (Courtesy of Greg Shay)

Dr. Greg Shay knew he might not return alive from Gaza. His wife Linda begged him not to go. His children staged an intervention over the phone, their voices heavy with desperation.

The 70-year-old retired San Francisco pediatric pulmonologist decided he had no choice. The Israel-Hamas war had cut off desperately needed medicine for young Gazan cystic fibrosis patients. The doctors he had trained there a few years ago felt abandoned.

He had to go back.

Before he left in early October, he sat in the quiet of St. Joseph's Basilica in San Francisco, facing his priest. "I want last rites," he said to his pastor, Fr. Mario Rizzo.

The priest hesitated. "I don't think you understand what last rites are."

Shay whispered: "I could die there," tears piercing the resolve of a man who, by his own admission, was usually a "hard-ass."

Rizzo gave Shay a special blessing, anointed him with chrism oil and urged him to take a rosary. Shay chose instead to rely on his 10 fingers for prayer, leaving behind his cherished Fatima and silver bead rosaries and carrying into Gaza only his faith and a Maximilian Kolbe medal in his pocket.

As Israel expands its military operation in Gaza, seizing large areas of land and ordering mass evacuations, the humanitarian crisis in the enclave is deepening. The offensive, described by Israeli officials as an effort to "crush and clear" Hamas, has claimed hundreds of Palestinian lives since the collapse of a ceasefire on March 18. Meanwhile, Israel continues to block humanitarian aid, and the United Nations warns that Gaza is teetering on the brink of famine. All 25 World Food Programme bakeries have shuttered due to a lack of flour and fuel.

The president of the Red Cross Mirjana Spoljaric on April 11 described the humanitarian crisis in Gaza as "hell on earth," warning that people lack access to water, electricity, and food, and that the organization's field hospital will run out of supplies within two weeks.

On April 13, Palm Sunday, Israel struck Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, the Associated Press reported. A child died during the evacuation because medical staff could not provide urgent care, according to Gaza's ministry of health, the report said.

The Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem, which runs the hospital, said the attacks destroyed a lab and damaged the hospital's pharmacy and emergency department buildings. The diocese said it was the fifth time the hospital has been bombed since the war began.

Displaced Palestinian children wait to receive free food at a tent camp, amid food shortages in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip, Feb. 27, 2024. (OSV News/Reuters/Ibraheem Abu Mustafa)

Shay has spent his life tending to children's fragile lungs, but in the last decade, his mission has expanded into war zones, refugee camps and disaster-stricken areas around the world.

"I'm from a very strong Irish Catholic family from Boston," Shay said. "I'm a cradle Catholic, and probably became more religious in college."

He worked three decades at a Kaiser Permanente health center, specializing in pediatric lung diseases and treating children with cystic fibrosis. He retired in 2014 with a dream that many doctors share: providing care to the world's most vulnerable.

"I don't go on these trips just because I'm a Catholic," he said. "I do it [as] a humanitarian. I'm a human being."

He made his first mission to the Middle East in 2016. "I kind of fell in love with the Syrian people," he said. He has worked at four Syrian refugee camps.

From Jordan to Greece, Lebanon to Syria, his work with the U.S.-based international humanitarian organizations MedGlobal and the Syrian American Medical Association has taken him into the heart of conflict, where displaced families struggle for survival.

His humanitarian work soon stretched across continents. He worked twice in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, spent six missions in the country overall, and traveled to Ukraine at the height of war to manage an orphanage for children evacuated from combat zones. He has gone on 35 medical missions since 2016.

Dr. Greg Shay heads into Gaza with a U.N. armored convoy from the Jordan-Israeli border in October. (Courtesy of Greg Shay)

Shay's wife, Linda, a pediatric dermatologist, has joined him on some trips since she retired in 2020.

"My wife is five years younger than I am, and so she's like, 'OK, well, you got five years to do what you want to do,' " Shay said. "There's no place I'd rather be than helping people around the world."

His journeys led him to Gaza twice before the war, in November 2022 and March 2023. His medical work there would take on new urgency after Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, killing about 1,200 Israeli civilians and taking more than 250 hostages. Gaza's Health Ministry said at least 50,000 Palestinians have died in Gaza since the Hamas attack on Israel.

Shay went to Gaza through MedGlobal in 2022 and 2023 to help set up a cystic fibrosis program.

The disease causes chronic lung infections and prevents patients from absorbing food without special medications. In the U.S., advances in treatment have extended life expectancy from 10 years in the 1960s to over 40 years today. But in Gaza, where access to essential drugs was restricted even before the war, children rarely lived past 15, Shay said.

Shay worked with local doctors, especially at Gaza City's Al-Rantisi Children's Hospital, to implement a treatment model similar to that of the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Centers.

His mission also included hosting a two-day conference to train nurses and pediatricians on managing the disease. The goal was clear: extend patients' lives into their 20s or 30s using the best available medications.

Dr. Greg Shay treats an 18-year-old patient with severe cystic fibrosis at Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza. Shay, a retired pediatric pulmonologist, made his third medical mission to Gaza in October. (Courtesy of Greg Shay)

But since the war, the Israeli government has blocked the most effective drugs, Shay said.

A month into the war, Israeli Defense forces targeted Al-Rantisi Children's Hospital, destroying all the equipment that Shay had bought during missions before the war. The IDF claimed Hamas had located its operational bases in tunnels under the hospital; hospital officials said Al-Rantisi's basement had been used as a shelter for women and children.

The war's impact on Gaza's fragile medical system was catastrophic. The destruction of Al-Rantisi forced doctors to relocate to Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis, where they struggled to care for about 150 cystic fibrosis patients from across the territory. Meanwhile, Israeli restrictions on aid deliveries cut off access to pancreatic enzymes — essential for patients to digest food — leading to malnutrition and death.

"Some of the kids died in bombings, but a lot of the kids have died from malnutrition because they haven't been able to get all of their medicines, or they've died of their cystic fibrosis because they haven't been able to get any of their breathing treatments or antibiotics," Shay said.

"We think there are only about 70 maximum of the 120 CF patients still alive in Gaza," he said.

Since December, no outside doctors have been allowed into Gaza. When Shay finally returned to Nasser Hospital in October, nearly a year after the war began, the health care system he had helped build was gone. His mission to give Gaza's cystic fibrosis patients a fighting chance was buried under the rubble.

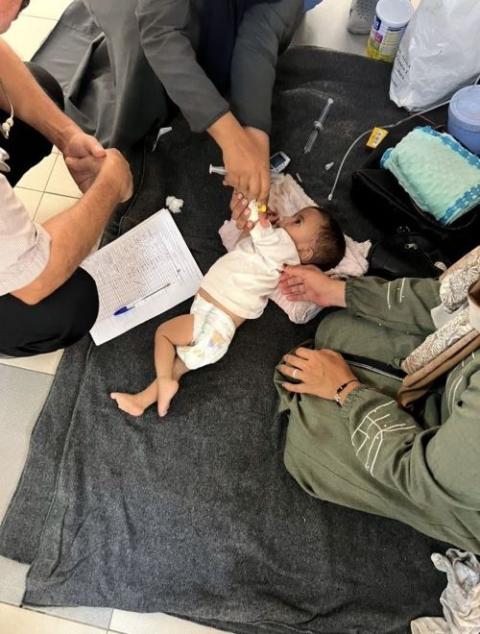

Shay said the hospital was stretched far beyond its 440-bed limit with 660 patients. The pediatric ward, designed for 40 beds, held 140 sick children. In many cases, two or three patients shared a single bed. Others lay side by side on thin mats in the overcrowded hallways where the hospital staff struggled to care for them with dwindling resources.

Due to overcrowding at Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis, Gaza, young patients were treated in the pediatric ward's hallways. (Courtesy of Greg Shay)

Most of the young patients suffered from pneumonia, meningitis, dysentery or malnutrition. Some bore the wounds of war: shot by snipers or missing limbs after bombings.

Infection spread through the hospital and the sprawling tent cities outside. Without soap or sanitizer — which Israel banned from entering Gaza — diseases flourished. "You might have 10 people living in a tent. One person gets the flu. Pretty soon, all 10 people have the flu," Shay said. "And pretty soon the next tent has the flu, or the hepatitis, or the meningitis, or the pneumonia, and it just spreads through the whole camp."

The war had decimated Gaza's medical infrastructure. Hospitals had been bombed and even those still standing lacked essential medicines. "The first thing they destroyed when they went into the hospitals was all the medical records," Shay said. With no microbiology lab, doctors were left guessing at diagnoses, unable to test for bacterial infections. Even when they had medicine, it often failed.

"We couldn't figure out why the medicines weren't working," said. Then, the answer became clear: The antibiotics had been left sitting in the sun for months because Israeli authorities had blocked medical shipments. The heat had rendered them useless.

Food was nearly nonexistent. Shay, like the doctors he worked alongside, survived on little more than bread, cheese and protein bars he had carried from the U.S.

"I usually had one meal in the evening, which was usually about two cups of rice and it might have some garbanzo beans, or some days it might have a few small pieces of chicken," Shay said.

He lost 12 pounds — "basically all muscle" — during the mission.

The Grand Palace Hotel stands damaged in Gaza City in the Gaza Strip Feb. 6, 2025, amid a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. The ceasefire collapsed on March 18. (OSV News/Reuters/Dawoud Abu Alkas)

Amid the chaos of war, looking at the rubble from his window at the hospital, Shay found solace in prayer.

"Mostly I tried to say the rosary every day, usually at night," he said. With limited media providing rare glimpses of the destruction unfolding across Gaza, he relied on faith to steady himself through the worst moments. "You pray more when there are bombs or explosions going off in the area," he said.

"I figured that what's going to happen is going to happen, and God's going to do what God's going to do," he said. At the hospital, he added, he would whisper silent prayers as he walked among the beds, holding onto the ritual that had guided him his whole life.

The resilience of the Gazan people gave Shay hope. "These people love life," he said, describing how, even in the dire conditions of the hospital, faith remained unshaken.

"Muslims pray five times a day," Shay said "Their faith is strong, and their faith is what keeps them going." Their gratitude also strengthened him. Despite their suffering, they reassured him with words of kindness.

Leaving Gaza was wrenching. He had wanted to stay longer — another two to four weeks — but his wife insisted he return home.

Back in San Francisco, Shay struggled with the stark contrast between the abundance in American grocery stores and the hunger he had witnessed in Gaza. He scrambled to send medicines and equipment to Gaza from California in late 2024. Those supplies still sit in Jordan, Shay said.

Shay's faith remains unshaken, perhaps even strengthened, he said, even if he carries a deep regret. He had hoped to visit Holy Family Parish in Gaza, to bring medicine to a child with cystic fibrosis that he treated in 2022. "We weren't allowed to travel at all," he said.

"My head's not quite back to where it was before I went to Gaza," he said, comparing his trauma to that of soldiers returning from war. His hope flickers amid ongoing violence and U.S. arms shipments to Israel, but he said he finds strength in the voices calling for peace.

Shay continues to struggle with returning to normal life. "Every day," he said, "I relive what I saw."

Advertisement

The emotional weight of the experience remains with him, especially as he stays in close contact with friends and colleagues still on the ground doing humanitarian work in Gaza.

He learned that Nasser Hospital, where he worked in the fall, had been bombed. Israel said it had been targeting a senior Hamas leader.

Shay said he had hope when he heard that Pope Francis had been talking with Catholics in Gaza every day, but he also thinks the pope could do more.

He would like the pope to call out "[U.S.] government officials who are allowing this war to continue, many claiming to be Catholic." He also encourages priests and other Catholics to call for a permanent ceasefire, for the U.S. to stop providing aid to Israel, and for people to empathize with Gazans.

"Silence is complicity," he said. "Remember, Christians are also being killed and starved in Gaza and the West Bank."