Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, gives a lecture in New York in January 1988. Pope Benedict, who previously headed the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for more than two decades, died Dec. 31 at the age of 95. (CNS/KNA)

When Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was elevated to pope in April 2005, perhaps no group in the United States was more familiar with him than Catholic theologians.

Before he became Pope Benedict XVI, Ratzinger spent nearly a quarter of a century (1981-2005) as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, where he quickly became known as a strict enforcer of official church teaching.

"His movement from the head of the CDF to the papacy felt more like a continuation than a new beginning," said Susan Ross, professor emerita of theology at Loyola University Chicago and past president of the Catholic Theological Society of America. "Benedict was by all accounts a brilliant theological mind, but he made the lives of theologians difficult."

Over the course of nearly 50 years, Benedict produced more than 65 books in theology, Christology and liturgy, as well as three papal encyclicals and three papal exhortations.

Yet, whatever contributions he made in his prolific and distinguished career may ultimately be overshadowed by the years he spent monitoring, and sometimes suppressing and silencing, the work of other Catholic theologians and ethicists. Though Benedict resigned from his papal office in 2013, many theologians in the U.S. still struggle to separate the pope from his tenure as the Vatican's doctrinal watchdog.

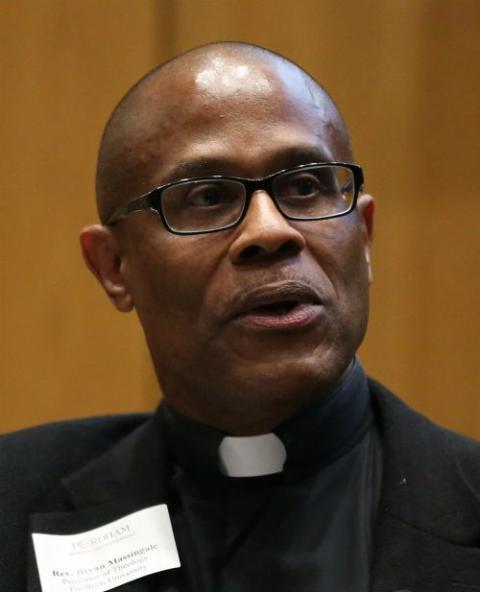

"It's impossible to look at his impact on theology only in terms of his pontificate," said Fr. Bryan Massingale, who served as president of the Catholic Theological Society of America from 2009 to 2010. "You have to look at his leadership at the CDF and his series of investigations into theologians."

Massingale, who holds the James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics at Fordham University, said that the scrutiny "contributed to an atmosphere of caution, hesitation, and even avoidance of certain topics by theologians."

Fr. Bryan Massingale (CNS/Fordham University/Bruce Gilbert)

History suggests that these investigations were not so much initiated by Ratzinger, but by the man who appointed him, Pope John Paul II. A 1979 article in The Washington Post heralded fears among theologians of a new doctrinal rigidity coming from the Vatican. The piece presented a litany of inquiries instigated in the first year of John Paul II's papacy. It spotlighted the then-newly opened case against Fr. Charles Curran, launched by then-prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Croatian Cardinal Franjo Seper.

When Seper resigned due to illness in November 1981, John Paul II immediately appointed Ratzinger to take over the helm at the CDF. Ratzinger took up the investigation of Curran, who was under scrutiny for criticizing the church's teaching on sexuality, particularly contraception.

Ratzinger summoned Curran to Rome for a meeting at the congregation's offices in March 1986. The German cardinal's reputation as a quiet, shy academic appeared to be on full display.

"He was a gentleman, very cordial," recalled Curran in an interview with NCR. "He offered me coffee."

Curran remembers a few tense moments in the two-hour meeting. When Curran suggested that many German theologians and ethicists shared his viewpoints, he seemed to stoke Ratzinger's ire. "He said, 'Are you suggesting that I launch an investigation into all of these theologians, too?' " Curran recalled.

Several months after the meeting, Curran received a letter from the congregation, stating that he was "not suitable nor eligible to teach Catholic theology." After several years of academic wandering, Curran was offered a tenured position at Southern Methodist University in 1991, where he remains Elizabeth Scurlock University Professor of Human Values.

"I think sometimes the office makes the person," Curran said. "Ratzinger saw himself as the enforcer."

A turn to the right

In progressive circles, Ratzinger's story is often recounted as a cautionary tale about a man who started out progressive and idealist, only to shift into a rigid conservative.

"Ratzinger was part of the majority [of theologians] that wanted the Second Vatican Council," said Dennis Doyle, professor emeritus of Catholic Theology at the University of Dayton, Ohio. "He wasn't anti-council and he wasn't a traditionalist."

Ratzinger's understanding of the task of church renewal did distinguish him from many of his fellow reformists, however. Rather than see the purpose of the council as aggiornamento, or an updating or modernizing of the church, Ratzinger stressed the work of reform as a ressourcement, or a return to the sources of the tradition, particularly the theology of the early church fathers.

Fr. Hans Küng, a prominent theologian who taught in Germany, is pictured in his office in Tübingen, Germany, in this February 2008 file photo. The Vatican, with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger's acquiescence, revoked Küng's license to teach Catholic theology. Küng died in 2021. (CNS/Harald Oppitz, KNA)

A year after the council concluded, Ratzinger joined the faculty of Tübingen University, where he took his place among emerging theological stars Hans Küng and Jürgen Moltmann. In 1968, two years into his tenure, a revolt broke out among German University students. Inspired by Marxist beliefs, the students rebelled against the elitism and exclusivity of the German university system.

The upheaval found its way into one of Ratzinger's lecture halls one day when a student ripped the microphone from his hands and began to protest. Horrified, Ratzinger left Tübingen shortly thereafter, and joined the faculty of the University of Regensburg.

"Most of us think of that moment as Ratzinger's symbolic shift to the right," said Doyle. "But in his mind, he was being consistent."

Rather than having a sudden conversion to conservatism, it may be more accurate to say that Ratzinger's concerns about the effects of change and modernity on the church were confirmed by the events of 1968. His fears had hardened him and led him to revert even more strongly to the theology of St. Augustine that had thoroughly shaped his religious imagination.

Dennis Doyle (Courtesy of Dennis Doyle)

Before and during his pontificate, Benedict often spoke of St. Augustine as one of his greatest companions in his life and his ministry. Augustine placed a strong emphasis on the corruption of human nature by sin and the necessity of grace for salvation. For Benedict, this grace came through the church.

"Benedict had this vision of the church as eternal because he believed that the idea of the church existed in the mind of God," Doyle said.

As an Augustinian, he was especially wary of the utopian ideas of Marxism that he saw played out by the revolt in Tübingen. He was alarmed by the notion that human beings could create a perfect world.

"For a lot of Augustinians, there is a lot of focus on sin in the world," said Curran. "There is a tendency to identify the city of God as the church, and the city of man as the world." This dualism made Benedict suspicious of worldly ideas.

Many theologians in the U.S. are, like Curran, theological Thomists. They believe that human beings are basically good and that human reason and experience gives us the capacity to learn moral wisdom and knowledge.

"We learn from the world," as opposed to being suspicious of it, Curran said. "I think that is the primary theological difference between Benedict and many theologians."

'One of his greatest fears was of the loss of transcendence of faith. He was afraid that contemporary theology had become too focused on social change.'

—Dennis Doyle

The investigations

Indeed, one could almost connect the dots between Ratzinger's deepest theological anxieties and the theologians and theological ideas that he scrutinized.

"One of his greatest fears was of the loss of transcendence of faith," explained Doyle. "He was afraid that contemporary theology had become too focused on social change."

This concern fueled his criticism of liberation theology, which he believed threatened to reduce the church to little more than a social program. It disturbed Ratzinger that people called themselves Christian without having an awareness of the transcendence of God. This led him, in 1985, to investigate and ultimately silence theologian Leonardo Boff, who at the time was a Franciscan priest.

"He also feared a loss of Christocentrism, or of seeing Christianity as one religion among many," said Doyle. Ratzinger's Dominus Iesus, which he published as a declaration of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 2000, criticized those who denied the distinctiveness of the Catholic Church and refuted the claim that other world religions could offer salvation independent of Christianity.

The declaration was written one year after Jesuit Fr. Roger Haight published his book Jesus: Symbol of God. Haight argued that other world religions could offer pathways to God alongside Christianity. In 2008, after years of investigation, the Vatican banned Haight from teaching and publishing.

The fisherman's ring — the pope's signet — is seen on the right hand of Pope Benedict XVI as he celebrates Mass in Havana, Cuba, March 28, 2012. When a pope dies or resigns the ring is destroyed in a special ceremony, usually carried out in private. (CNS/Catholic Press Photo/Alessia Giuliani)

Ratzinger's worry about the loss of Christocentrism was further provoked by the 2004 book Being Religious Interreligiously: Asian Perspectives on Interreligious Dialogue, written by Peter Phan, who at the time was a Salesian priest. Phan's book set off inquests both from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the doctrinal committee of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, who claimed that it did not adequately profess Jesus Christ as the unique and universal savior, or the role of the church as the sign and instrument of salvation.

Though Phan was never personally disciplined, the bishops' conference did issue a statement declaring that the book contained "certain pervading ambiguities and equivocations that could easily confuse or mislead the faithful."

Reflecting on the experience in a 2017 interview with NCR, Phan said Benedict was "was blinded by his deep fear of what he called the 'dictatorship of relativism.' "

"He was unable to appreciate the intellectual questions and the spiritual quest behind the theologies and the theologians he condemned," said Phan, who is the Ignacio Ellacuría Professor of Catholic Social Thought at Georgetown University.

Perhaps the most well publicized condemnation of a book by the CDF during Benedict's pontificate came in its criticism of Mercy Sr. Margaret Farley's Just Love: A Framework for Christian Sexual Ethics. Published one year after Benedict's election, the book proposes a seven-point ethical framework for evaluating whether a sexual relationship is true, loving and just.

The book expectedly created consternation in Benedict who, like Augustine, showed a particular preoccupation with the sinfulness of sexual desire. During his time at the CDF, some of Benedict's most prominent work came in his harsh doctrinal criticisms of sexual relations outside of marriage and of same-sex relationships.

In 2010, the CDF officially declared that Just Love could not "be used as a valid expression of Catholic teaching, either in counseling or formation, or in ecumenical or interreligious dialogue," though Farley herself was not silenced or barred from teaching or writing.

There is one common denominator shared by all of the investigations that took place during Benedict's time at the CDF and as pope: Nearly every theologian who faced disciplinary action was a member of a religious community.

Curran said that wasn't a coincidence. "They go after those with a religious superior," he said. "If theologians are not in a religious community, you really can't do much to them."

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith can threaten the canonical status of a religious congregation.

"The whole system is unfair," said Curran, because it makes entire religious communities vulnerable.

Countering feminism

For all Benedict's theological angst, perhaps no modern movement caused him more concern than the push for women's equality and its influence on theology in the 1980s. And perhaps no one had a more dramatic clash with Benedict's drive to curb the emergence of feminist theology than St. Joseph Sr. Elizabeth Johnson, whose application for tenure at the Catholic University of America Ratzinger personally obstructed in 1987.

As a pontifical university, Catholic University of America's applications for tenure in the field of theology required approval by the CDF. Ratzinger sent Johnson a list of 40 questions, focused particularly on an article she had written that questioned the church's image of Mary as humble and obedient. Her responses to the questionnaire did not satisfy Ratzinger, so he took the extraordinary measure of calling every cardinal in the U.S. to fly to Washington, D.C., to personally interrogate her.

In the end, Johnson became the first women to receive tenure at Catholic University of America. But it wouldn't be her last tangle with the church's hierarchy.

Advertisement

St. Joseph Sr. Elizabeth Johnson (CNS/Fordham University)

In 2011, Johnson's 2006 book Quest for the Living God was criticized by the U.S. bishops' conference, whose doctrinal committee declared that the book "completely undermines the Gospel and the faith of those who believe in God."

Its feminist themes were a particular sticking point for the nine-man committee, which argued that the titles that the church uses for God cannot be supplanted "by novel human constructions" aimed at "promoting the socio-political status of women."

The incident was a glaring example of the way in which the Vatican had empowered local doctrinal committees to investigate theologians who were working within their dioceses.

"Under Benedict's pontificate, the doctrinal committee of the local episcopal conference soon became the pivotal committee in the local hierarchy," said Massingale.

It became a "super committee," Massingale said, that "contributed to a chilling effect and even lack of creativity when it came to taking on neuralgic issues of sexuality, gender and contraception."

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger greets Pope John Paul II during a 2004 ceremony at the Vatican. (CNS photo/Catholic Press Photo)

Theology persisted

Johnson, like other colleagues who faced an inquest by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith or the U.S. bishops' doctrinal committee, spent years corresponding dutifully with the hierarchy. In retrospect, she sees how the formation process of becoming a theologian actually offers excellent training for such inquisitions.

"You have to learn how to consult sources, mount an argument and think critically about ideas and practices," Johnson said. "So if someone in the CDF criticizes a theologian's work, there is no in-built habit that said stop."

The rigors of earning one's doctorate in theology and securing a teaching position and tenure promote independence of thought. But, at a deeper level, most theologians operate out of a profound sense of vocation.

"Deep down it is a call to serve God by thinking and teaching about the meaning, beauty and challenge of faith," Johnson said. "When criticism comes, from within or without the church, it certainly matters, but it doesn't make you stop because your work is coming from a deep internal source."

For all his efforts to control or suppress theological inquiry, Benedict's success remains questionable. One could argue that, during his 24 years as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and his eight years as pope, theology actually thrived.

"During his time, look what has emerged: liberation theologies of all kinds, feminist theologies, interreligious dialogue, different ways to deal with moral issues in the contemporary world," Johnson said.

"I think this richness shows that theology as a vocation is empowered by the Spirit," she added. "And she will not be quenched!"