A program for the Holy Name Society of St. Bridget's Parish Second Annual Minstrel Show, April 7,8 and 9, 1947, at the Parker Street Hall in Maynard, Massachusetts (Courtesy of Maynard Historical Society Archives)

Jesuit Fr. Joseph Brown was in high school when he and his father attended a show sponsored by a local chapter of the Knights of Columbus in 1960. The show was advertised as a fundraiser and a "great time" for the entire community, he said. Sitting in the audience, Brown and his father were surprised and put in an uncomfortable position when performers in blackface appeared on stage. They were at a minstrel show.

"At that time, as the only two black people in the building, my father was not going to say something," Brown said. "We were not going to talk about it."

Recent revelations in Virginia involving the governor and attorney general, both of whom have admitted to using blackface in the 1980s, have brought national attention to the long history of blackface minstrelsy in this country.

Little noticed in that history is the Catholic Church's connection to the offensive practice — a connection that goes back to the very beginnings of blackface minstrelsy.

According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, blackface was first popularized in 1830 when white entertainer Thomas Dartmouth Rice rose to fame by painting his face black and performing as the character "Jim Crow," a disabled African-American slave. Historian Rhae Lynn Barnes wrote on her website, U.S. History Scene, that the minstrel show format was born a decade later when a theater troupe called the Virginia Minstrels performed in New York City in 1842 — "a full night of blackface entertainment featuring black political mimicry, exaggerated African inspired plantation dances, and dialect songs."

As minstrel shows rose to prominence as one of the most popular forms of American entertainment, the U.S. simultaneously experienced a wave of Irish-Catholic immigration. According to the Library of Congress, the Irish, fleeing the Potato Famine of 1845, made up nearly half of all immigrants to the United States in the 1840s.

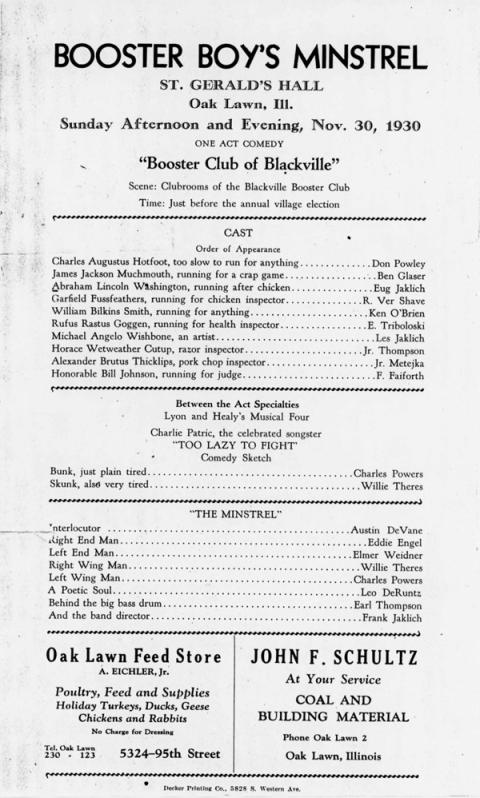

[At right: Flier given to attendees of the St. Gerald Catholic Church minstrel show entitled "Booster Boy's Minstrel," Nov. 30, 1930, in Oak Lawn, Illinois (Courtesy of Oak Lawn Public Library)]

Initially, according to Ball State University English professor Robert Nowatzki, the Irish were considered racial "others," in part due to their Catholic religion, and were similarly ridiculed by minstrel show characterizations. However, Irish-Americans quickly began donning blackface and participating in minstrelsy themselves in order to become more "white" and "American" by denigrating African-Americans.

"Blackface was at one and the same time a displaced mapping of ethnic Otherness and an early agent of acculturation," cultural historian Eric Lott wrote in his book Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class.

In his paper, "Paddy Jumps Jim Crow," Nowatzki argued Irish-Catholic participation in blackface minstrelsy "helped to shape the meanings of blackness, whiteness, ethnicity, and American nationalism — all issues that dominated the minstrel stage during the mid-19th century."

By the turn of the 20th century, minstrelsy was no longer the preeminent form of popular entertainment in the U.S. However, communities, schools and Catholic churches across the country continued to stage blackface minstrel shows for decades, perpetuating negative and offensive stereotypes of African-Americans among multiple generations.

"[The Rev. Martin Luther] King and [James] Baldwin said it: the most segregated times in America were Sunday mornings.

There was nobody there to challenge it."

—Jesuit Fr. Joseph Brown

Brown, who is now a professor of Africana Studies at Southern Illinois University, believes the prominence of minstrel shows in parishes was tied to the segregation of the church in the first half of the 20th century. Because of that separation, there weren't many who questioned the ethics of blackface minstrelsy in white communities.

"[The Rev. Martin Luther] King and [James] Baldwin said it: the most segregated times in America were Sunday mornings," Brown said. "There was nobody there to challenge it."

In his book, Black, White, and Catholic: New Orleans Interracialism, 1947-1956,* Jesuit Fr. Bentley Anderson, professor of African and African-American Studies at Fordham University, wrote that minstrel shows were an expression of New Orleans Catholics' prejudiced views of blacks.

Anderson found that St. Henry's Church in New Orleans hosted a minstrel show as an annual parish fundraiser during the 1940s and 1950s. "Especially under the church auspices, this form of entertainment not only confirmed stereotypes of African Americans as childlike and inferior, but also gave white Catholics permission to ridicule blacks," he wrote in his book.

"Minstrel shows were a given," Anderson told NCR. "Few people questioned race relations."

Examples of Catholic churches and organizations hosting minstrel shows were not limited to the South. Organizations like the Knights of Columbus, the Catholic Daughters of America and the Catholic University of America hosted or sponsored minstrel shows across the country, from Washington, D.C. to Massachusetts to Illinois.

Antonette Weber, 86, remembers performing in a minstrel show as a young girl in the 1940s at St. Joseph's Church in Kingston, New York, though she wasn't in blackface. She doesn't remember there being any black parishioners at St. Joseph's back then, but said that nobody questioned the blackface skits included in the show.

"Everyone enjoyed it," Weber said. "At that time, we wouldn't have had black people to object to it."

According to sociologist Leslie Picca, it is important to note that while blackface was considered "fun entertainment for white individuals," African-American communities have been resisting racist practices like blackface "since the beginning of the slave trade." Even at the height of blackface minstrelsy's popularity, there were people speaking out against it.

Brown recalled being cast by a nun as "Rastus," a racist minstrel archetype, for a school performance and instructed to "speak more southern" in rehearsals as a seventh-grader in 1957. When his mother found out, she confronted the nun after Mass at their parish, St. Jude's Church, and pulled Brown out of the show.

"There were never enough of my father and mother to critique [minstrelsy]. It kept on going because the Catholic Church was totally segregated as far as color goes," he said.

Advertisement

Brown said that he does not "live with how horrible this was," but instead draws lessons from the painful history of racist portrayals of African-Americans in this country.

"This is how you've been seen, so how do you want to show yourself?" he said.

It is not clear exactly when churches stopped hosting minstrel shows. The recent backlash against blackface speaks to social progress, said Picca, who is chair of the department of sociology, anthropology, and social work at the University of Dayton. Nevertheless, the situation in Virginia is a stark reminder that blackface continues to affect society.

"Oftentimes people see blackface as a legacy of past racial practices without recognizing that we still see impacts today," said Picca. "This impacts everybody's humanity and morality," she said.

Brown, who has studied theater and film, sees how the negative stereotypes in blackface minstrelsy still linger in comedy and popular media today. "What always breaks my heart is the people that don't even know they are participating in perpetuating that," he said.

He believes Gov. Ralph Northam is another example of someone who is "sorry because they got caught." He hopes that in the future, more people of privilege will take initiative to validate those who feel oppressed and harmed by practices like blackface.

"I'm going to fight for that every day that I teach, and every day that I preach, and every day that I live public because my parents taught me to," he said.

[Jesse Remedios is an NCR Bertelsen intern.]

*This story has been updated to correct the title of Anderson's book.