The legend of St. Francis and Brother Wolf is a story not of taming, but of cooperation and mutual understanding, writes Nancy F. Castaldo. The legend stands as a reminder that true peace comes from cooperation, not domination, and that even our adversaries have a place in God's creation. (Nancy F. Castaldo)

"Praised be You, my Lord, with all Your creatures." These timeless words were penned by St. Francis of Assisi about 800 years ago in his hymn, "The Canticle of the Creatures." Within these verses, Francis offers a profound vision of creation as a living, breathing brotherhood and sisterhood, where even the wind, fire and moon are part of a divine family.

Francis viewed God as Our Father, with the Earth as Mother and all living creatures — down to the smallest ant, flowing rivers and even wolves — as siblings. This radical idea of creation as a fraternity, tied together in God's grace, was the foundation of Francis' life of simplicity and communion with nature.

Composed toward the end of his life, "The Canticle of the Creatures" might very well be the earliest piece of Italian literature, written in the Umbrian dialect. Its simple yet profound message of universal harmony continues to resonate today, particularly when we consider the example set by Francis in his legendary encounter with the wolf of Gubbio.

The legend of St. Francis and Brother Wolf

The legend of Francis and Brother Wolf is set in the town of Gubbio, not far from where Francis lived. Gubbio was plagued by a fearsome wolf that was terrorizing the villagers, killing their livestock and even attacking people. Despite numerous attempts to kill it, the creature continued to terrorize the town. Desperate, the townspeople turned to Francis, known for listening to God's voice and having an ability to speak with animals.

Francis, ever compassionate and empathetic, approached the situation with a unique perspective. Instead of seeing the wolf as a threat to be destroyed, he saw an opportunity to understand the creature's plight. Following prayer, Francis ventured into the woods to meet the wolf.

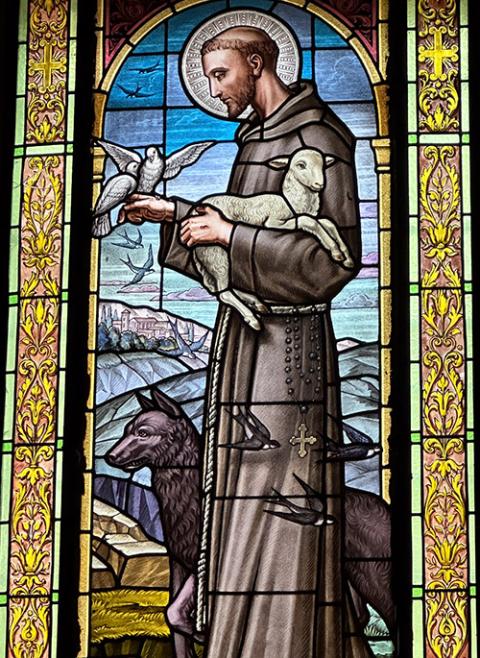

St. Francis with Brother Wolf is depicted in the stained glass in Chiesa Parrocchiale di San Filippo e San Giacomo (Church of St. Philip and St. James), a Catholic church in Rueglio, Italy, outside of Turin in Italy's Piedmont mountain region, where wolves currently coexist with wildlife and farmers. (Nancy F. Castaldo)

"Come, Brother Wolf, I will not hurt you," Francis called, making the sign of the cross and speaking words of peace. The wolf, known for being fierce and elusive, froze. But soon realizing Francis meant him no harm, the wolf approached. It sat in front of the saint, ready to engage in conversation.

The dialogue between the two reveals much about Francis' approach to creation. He viewed the wolf not as a mindless predator but as a creature driven by hunger and survival. Injured and abandoned by his pack, the wolf was forced to hunt livestock, weaker and slower prey, since he could no longer chase after the deer he once hunted. Francis understood that the wolf had attacked people only when they had attacked him first. Seeing the wolf's sorrow, Francis proposed a solution. In exchange for peace, the people of Gubbio would feed the wolf and the wolf would protect them. In turn, the wolf would no longer harm their livestock or residents.

Thus, the legend of St. Francis and Brother Wolf was born — a legend not of taming, but of cooperation and mutual understanding. The wolf was not subdued, but rather acknowledged as part of God's creation, deserving of compassion and care. The townspeople accepted Francis' proposal, and peace was restored. The wolf became a protector of the town, living harmoniously alongside the villagers.

This legend has endured for centuries, and in northern Italy, where wolves still roam, it is immortalized in the stained-glass church windows where locals gather to pray. It reminds us that coexistence is possible. The image of Francis and Brother Wolf stands as a reminder that true peace comes from cooperation, not domination, and that even our adversaries have a place in God's creation.

Advertisement

Learning to live alongside a keystone species

In the shadow of the Alps, outside Torino, Italy, the legacy of Francis continues to echo. Villages tucked into the mountainsides, their medieval stone houses perched among the grazing fields, still resonate with the spirit of the saint. There, cowbells chime in rhythm with the landscape, and guardian livestock dogs keep watch over the herds. Maremma sheepdogs, ancient protectors of livestock, echo the saint's legacy by safeguarding both the sheep and the wild predators who roam the land.

The relationship between farmers and wolves remains complex around the world but not insurmountable. Research by North American ecologist Stephen Kellert suggests that human attitudes toward wolves are shaped by cultural and historical factors, as well as our knowledge of the species. Despite their reputation as threats to livestock, wolves are essential to the health of ecosystems. They are keystone species, influencing the populations of other animals and ensuring a balanced environment.

In Italy, for example, the reintroduced grey wolves of the Apennine Mountains have become crucial to maintaining a healthy balance by controlling deer populations that might otherwise overgraze plants and disrupt the ecosystem. The same is true in America's Yellowstone National Park and Isle Royale National Park.

A statue of St. Francis of Assisi and a wolf is seen May 30, 2015, in the town of Gubbio, Italy. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

However, the conflict between wolves and farmers is not a simple matter of predator versus prey. In the same way that Francis found a way to bridge the gap between the wolf and the villagers, modern farmers across the globe have found solutions to prevent clashes between wolves and livestock. Non-lethal methods, such as using guardian dogs, fencing and even lighting and sound systems, are employed to keep both animals and people safe.

In the northern Rockies of the United States, reintroduction efforts for grey wolves have faced challenges as ranchers work to protect their livestock. Despite tensions, non-lethal solutions also include turbo fladry — bright red flags that blow in the wind, deterring wolves. Non-lethal solutions have been effective in reducing wolf attacks on livestock while allowing both the wolves and farmers to coexist.

Wolves, wherever they live, are not just creatures to be feared or killed; they are vital to the health of their ecosystems and offer a deeper lesson in cooperation. Their social structure, centered around family and teamwork, mirrors Francis' vision of creation. Wolves live in packs, working together to hunt, raise pups and maintain balance in the wild. They are resourceful and resilient, capable of surviving for days without food, but always with the support of their pack.

It is in this spirit of cooperation and understanding that we find the true lesson of Francis and Brother Wolf. We must remember that all creatures — whether predator or prey — are part of a larger, interconnected system, deserving of respect, compassion and care. Like Francis, we must recognize the sacred balance that binds us all, human and animal alike.

The story of St. Francis and Brother Wolf is not about taming wildness, but about recognizing the sacredness of all life and working together to ensure the harmony of our shared world.