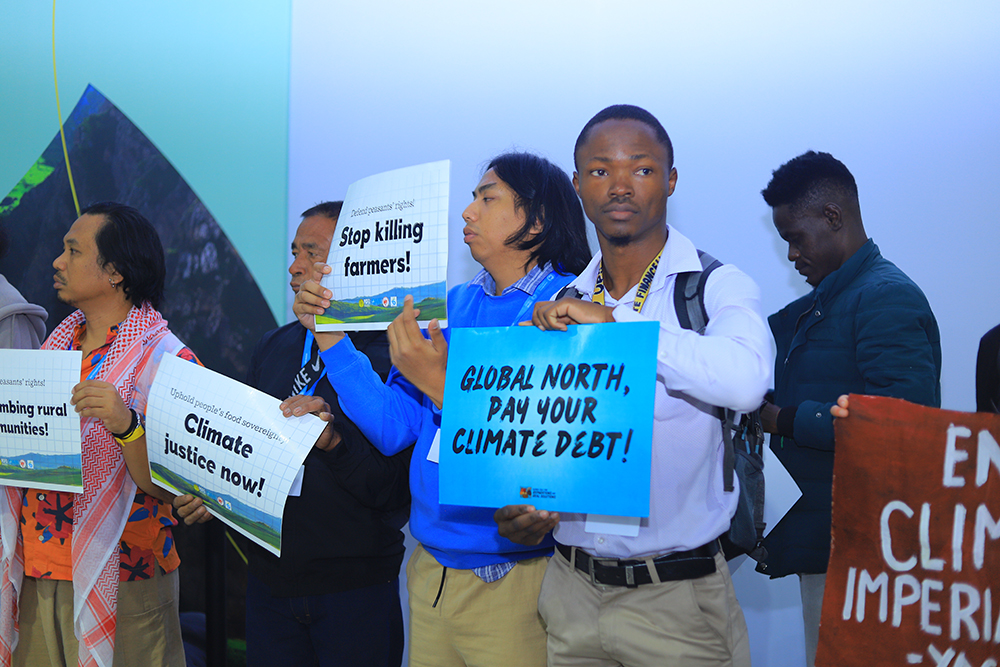

A climate activist takes part in a demonstration Nov. 18 at the COP29 United Nations climate change conference in Baku, Azerbaijan. (EarthBeat photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Most of what's been written about the recently concluded United Nations climate change summit in Baku, Azerbaijan, has focused on the failure of the parties to guarantee funding for developing countries. No one should be surprised, and most of us should be relieved. To paraphrase G.K. Chesterton, "It isn't that climate finance has been tried and found wanting, it's been untried and found difficult."

It is to the difficulties surrounding climate finance that the Catholic Church, particularly through its many universities, may be of invaluable help, and thus the reason for this immodest proposal.

As with other U.N. conventions established to address serious global problems, the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change has the propensity to skip over the hard part and take the easy way out — create a fund — rather than solving the reasons why such a fund may be necessary in the first place.

The Framework Convention is correct, a massive amount of funding is needed to ignite the structural changes required to respond to climate change. How much money, where it comes from and how it will be used are the perennial questions that COP negotiations wrestle with each tiring year.

Advertisement

In 2009, climate negotiations agreed that developed countries would contribute $100 billion per year by 2020. That money hasn't materialized as expected, so in November negotiators at the COP29 summit in Baku sought to up the ante, proposing $1.3 trillion annually by 2035. In the end, wealthy nations committed $300 billion and agreed to a "roadmap" to scale up to the $1.3 trillion target. The results were easily predictable.

There are many reasons why developed countries aren't going to offer up an additional climate fund for developing countries of the magnitude that is needed.

For decades, governments under the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development provided foreign assistance money to developing countries to address climate action. But the real money lies in private investment accounts: JP Morgan, Citi, Blackrock, etc. So why aren't private banks funding climate projects in developing countries? The answer is simple: risk.

It's a risk of either not returning the requisite return on equity investments — whatever that may be — or not receiving loan repayments, a very real possibility as developing countries are already writhing under a leaden blanket of debt.

So why is the risk so high in so many developing countries?

Simply put, there's a lack of capacity (and sometimes will) in many countries to establish the requisite policies and regulations that will ensure sound investment behavior and successful business enterprises, thereby lowering the risk of doing business in that country. As the former head of environmental finance at Citigroup liked to tell me when we discussed these matters, "Fix the institutions and the money will find you."

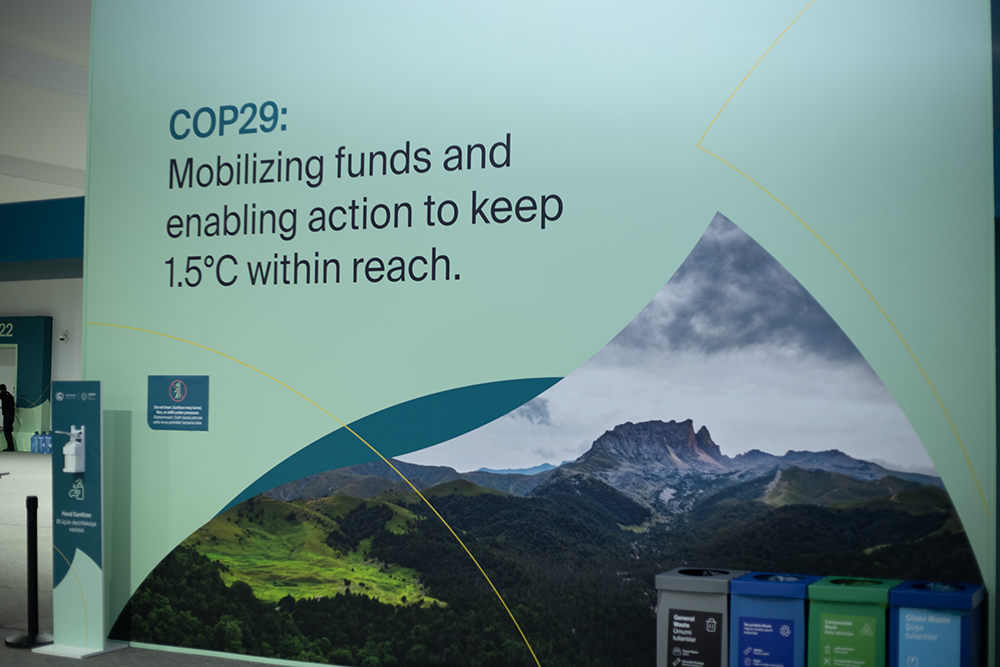

At COP29, the United Nations climate change conference in Baku, Azerbaijan, nearly 200 nations adopted a new target for climate financing of $300 billion. It was well short of the $1.3 trillion developing nations sought. (EarthBeat photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

This brings us to Catholic education, more specifically, the multitude of Catholic universities that span the globe.

According to the Vatican's Congregation for Catholic Education, there are more than 1,300 Catholic universities and higher education institutions in the world (U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops puts the number at over 1,800). Regardless of the number, that is a lot of students, graduate students and professors.

Most of these universities offer graduate programs in disciplines like science, engineering, business, finance and public policy. So how can these students and faculty help?

Typically, graduate programs require capstone projects to earn advanced degrees. These projects are often practical, real-world research projects performed on behalf of a client outside of academia looking for a solution to a particular problem.

When I worked at the U.S. State Department and taught at Georgetown University, I sponsored capstone projects from Georgetown graduate students who would provide high-level analytical support for a particular foreign policy problem. Thus, the State Department received insightful analysis it needed to fulfill its mission — for free — and the students were able to apply their expertise and passion to real-world problems.

Students and professors alike yearn to have their expertise and knowledge applied to real-world problems, to have their research and analysis have a practical impact, to have their scholarship manifest in ways far beyond journal articles.

There are many reasons why developed countries aren't going to offer up an additional climate fund for developing countries of the magnitude that is needed.

This interest for practical applications of advanced and cutting-edge research finds a growing need throughout the developing world, particularly around climate change. Developing countries often lack funding to pay high-priced consultants around mitigation and adaptation strategies. Bilateral and multilateral foreign assistance funding will never be enough to effect the kinds of structural change required.

Local and regionally based Catholic universities around the globe could help provide the expertise, innovation and creativity to climate challenges that can benefit developing countries. What is lacking is the institutional connective tissue that links them together.

Addressing in January the International Federation of Catholic Universities, Pope Francis said, "We must always ask ourselves: What is the purpose of the learning we impart? What is the transformative potential of the knowledge we produce? What and whom do we serve? Neutrality is a mirage. A Catholic university must make choices, choices that reflect the Gospel. It must take a stand and clearly show it in its actions, 'getting its hands dirty' in the spirit of the Gospel and for the transformation of the world and in service to the human person."

Let's help Catholic educators and students "get their hands dirty" by connecting them to countries in need of addressing climate change, thereby accelerating the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

A Catholic Climate Capstone Network would link willing graduate students and faculty to developing countries seeking solutions. By building local capacity and assisting in the development of necessary policy and regulatory structures that are prerequisites to enhanced financial investments, Catholic institutions of higher education can help deliver on the Gospel's promise and the pope's exhortations.

There is a wide range of services and support these universities can provide to developing countries: agricultural services, infrastructure project management, accounting and financial oversight, energy regulatory policy and much more. Furthermore, such a constellation of universities addressing Indigenous and local problems is an elegant example of the church's principle of subsidiarity in action.

Students study in the library of the Pontifical Biblical Institute, part of the Gregorian University in Rome, in this undated file photo. (CNS/Courtesy Pontifical Gregorian University)

The recently concluded COP29 was yet another demonstration of the serious limitations of today's Framework Convention negotiations and a cry for new ways of collectively confronting the climate challenge.

So far, the Holy See's 2023 entry as a full party to the Framework Convention has not had the impact many had hoped, either in the negotiations themselves as an honest broker or in more ambitious convention commitments. Perhaps Rome should invest some of its organizational expertise and its interest in climate action to catalyze a global architecture that links Catholic universities to countries in need of fresh insights.

Design models for such a network abound and are available for emulation. What is needed is the commitment of those with the power to make such a contribution to take action.

Catholic universities' practical engagement throughout the developing world is no substitute to the trillions of dollars needed to restructure and grow these economies in light of climate change, but it could very well play a critical role in ensuring that such investment dollars will eventually come.