The Basilica of St. Francis with its bell tower is pictured through corn in Assisi, Italy, Sept. 6, 2011. (CNS/Paul Haring)

At the start of a recent stay in Italy that began in Rome and ended in Milan, my wife and I took the train from Rome to Assisi. It is the second time I've done that trip, and my initial reaction this time was that one should stop somewhere for a day in between to buffer the jolt moving from the outsized expressions of papal power in Rome to the simplicity and even sacred quiet of the holy spots in that Umbrian town.

Then I had a second thought. We live constantly, don't we, in that tension between authority and charism, between exuberant freedom and institutional necessities, between Francis at the moment of conversion and the Franciscan reality as it has played out over centuries.

The church, in its most visible institutional forms, can make for an easy target, and there are times when it deserves that designation. The contemporary betrayal of the community by its leaders will certainly go down as one of the worst and most compromising eras in its history. The best hope — given that we're humans, not angels, and thus still in need of institutions — is that it survives purified and humbled in the best sense.

We've suggested in the recent past that the church might do well to move Michelangelo's breathtaking Pietà from the back right corner of St. Peter's Basilica and change places with the papal chair (NCR, March 8-21) so that that moving representation of humility and abandonment might be our center of attention during this trying period.

Even in the best case, however, the tension remains. If there is a catch-breath magnificence to the Vatican that inspires a certain kind of awe, it is Assisi and the reality of its good saint that draws us to the essential core, the Christ mystery, the immutable paradoxes of death as life, vulnerability as strength, surrender as victory. And yet few of us live at either pole, at least not for very long. I could no more follow the footsteps and practice of the mendicant than I could imagine myself draped in watered silk and having to abide 15th-century court manners while attending to Vatican politics.

I recall having that same sense of in between when I attended the beatification of Franz Jägerstätter in Linz, Austria, in 2007. A simple farmer, husband and father, hardly a radical and certainly not a pacifist (he had once belonged to the Austrian army), he concluded, in his reading of Scripture, that the Germans were conducting an unjust war and he refused to serve their ambitions. And that was it. The conviction was so deep that he went off to prison and was beheaded in 1943 for his resistance.

The bishop of Linz, at the ceremony where 5,000 packed into the local cathedral, said Jägerstätter's "love of God did not allow any apathy. It demanded a clear differentiation between good and evil."

Advertisement

I found it fascinating, and still do, that the pope responsible for his beatification was Benedict XVI. In reporting on the event, I wrote:

The young Joseph Ratzinger grew up in a succession of small towns in southern Bavaria, just a few miles from Jägerstätter's hometown of St. Radegund. According to Erna Putz, a local journalist and longtime friend of the Jägerstätter family, the future pope who would declare Franz Jägerstätter "blessed" visited St. Radegund as a child and recalled those visits during a later appearance in the town as a cardinal. If there is a symbol for the underlying ambivalence that sometimes surfaced here in conversation about the beatification, it is the fact that Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, was briefly a member of the Hitler Youth when membership was mandatory and had his studies interrupted in 1943 when his seminary class was forced into military service. Later, still a teenager, he was drafted into the regular army and served in a variety of capacities until he deserted in 1945, ending up as an American prisoner of war.

In 1943, the simple farmer was beheaded for his conviction. The same year, the seminarian was forced to join the German Army and acquiesced. I can see myself far more clearly imitating the path of the young Ratzinger than having the courage of the adult Jägerstätter's conviction unto death.

Most of us are not called to those extremes or forced to make such decisions. I certainly have remained, despite convictions, a safe distance from prison. And yet between Rome and Assisi, between forced military service and the beheading block, there is no question about toward which pole I wish to be tugged. Rome may be necessary to a certain order and discipline, but we revere what happened in Assisi; that's what sings to the soul and gives hope in dark times. We may understand the compromises that found young Germans joining the Nazi youth, however reluctantly, or being swept up by a rip tide of history that has a seminary class taking up arms. But we beatify the farmer who read his Scripture and decided that the only path was to say no.

I recall, too, writing home from my hotel room following that ceremony and remarking that every time I was on the brink of walking away from an institution that had so betrayed our trust, the same institution would do something so right and holy that I was compelled to stick around to see what came next. I have in mind more often than not these days a wonderful line from the late Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan: "We live at the intersection of mysterious freedoms, God's and our own."

* * *

It is easy, given the natural beauty of Assisi and the surrounding region of Umbria, to understand how St. Francis became the patron of what we today call "integral ecology," the awareness that to be fully human is to be connected to all of creation and to treat that creation with reverence. Francis the saint, as the pope who took his name writes, "invites us to see nature as a magnificent book in which God speaks to us and grants us a glimpse of his infinite beauty and goodness."

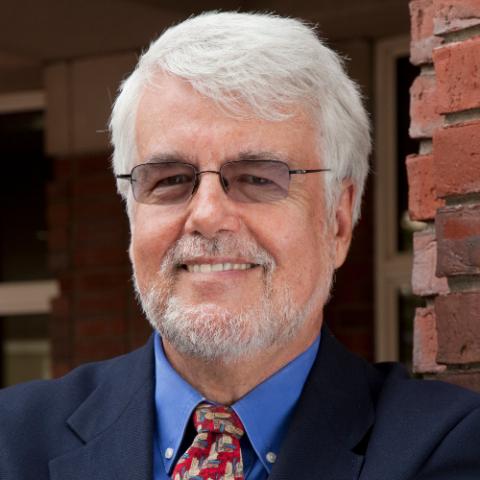

(Bill Mitchell)

The Earth itself presents us today with the issue that does "not allow any apathy." This is the issue that may bring us all to an extreme moment. The threat is spelled out in abundant, even overwhelming science, and the connection between that reality and our faith is made clear in Pope Francis' encyclical, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home."

I've announced in this space earlier that we are making special efforts to place reporting on the Earth, the threat posed by climate change and what is being done about it, at the top of our list of concerns. Staff writer Brian Roewe has been an essential part of that reporting effort for several years. But that effort has been boosted recently when Bill Mitchell came on board as climate editor. The two have already begun working together to advance our coverage and to increasingly connect with the amazing array of Catholics in the United States and well beyond who are deeply committed to working on solutions to the climate crisis.

Mitchell has a long and distinguished journalism career and is no stranger to NCR. He wrote his first story for us while a student at Notre Dame in 1967 and was a member of the board from 1998 to 2004. In his own words, he is a journalist and teacher with "stops along the way" at the Detroit Free Press, Time, the San Jose Mercury News, Andrews McMeel Universal, the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, Harvard's Shorenstein Center and Northeastern University. He and his wife, Carol, a spiritual director, live in Brookline, Massachusetts.

"There's no more important story in the world these days," Mitchell said of his new assignment, "and no more appropriate news organization to pursue it than NCR. I count myself lucky to be joining the effort."