The Adele Center, a student residential facility at the University of Dayton opened in 2019, includes a 53.4-kilowatt Melink solar array. (University of Dayton)

In June 2014, the University of Dayton ventured into fairly uncharted territory for a Catholic college, much less any academic institution in the United States.

The Marianist school in western Ohio made the public commitment to divest its entire investment portfolio — then $670 million, with half a billion in its endowment — from the fossil fuel industry.

The decision wasn't an easy one to reach, nor was it a fast one to implement. To add to the complexity, there were few examples out there of how to go about it, as fewer than 10 universities nationwide at that point had made the move to cut ties with fossil fuels.

In a way, Dayton was out on a limb, especially among Catholic institutions in the United States.

It would be another year before Pope Francis released his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," meaning leaders at Dayton couldn't tap into the pope's prophetic message for consultation or ground their decision-making in the document. Without it, they were unable to tap into a mobilizing refrain from the encyclical that has since compelled nearly 200 other Catholic organizations, religious orders, dioceses and schools to abandon the financing of fossil fuels: "We know that technology based on the use of highly polluting fossil fuels — especially coal, but also oil and, to a lesser degree, gas — needs to be progressively replaced without delay."

Six years later, the story of how Dayton, now completely divested for more than three years, moved through the process of deliberation and implementation has become clearer. So, too, are early consequences for the university's bottom line.

The decision

Conversations about fossil fuel divestment first began at Dayton in 2013 in the investment committee of the board of trustees as part of a wider discussion about mission and socially responsible investing.

Members of the investment committee serve as fiduciaries, charged with the responsibility to best manage the university's financial future, its endowment. Among the duties is developing an investment policy for the endowment and setting asset allocation strategies and employing screens to avoid investments in ventures that conflict with the school's mission and values. Like many Catholic institutions, Dayton had previously set screens in such areas as tobacco, abortifacients and pornography. To that point, though, the university had not considered fossil fuels.

Daniel Curran, Dayton's president as it considered divestment, told NCR in 2014 that the sense among the committee at the time was that divestment "was something we should be looking at when you talk about socially responsible investing." He said the committee entered the process "in an unbiased way" and considered many factors, not the least its values as a Catholic and Marianist academic institution. It was "a mission-based discussion," said Curran, who retired in 2016.

As talks at Dayton began, the fossil fuel divestment movement was just beginning to gain steam. Only a handful of schools, cities and faith groups had publicly committed to cut financial ties with fossil fuel companies. In November 2012, the grassroots climate activist group 350.org launched its Go Fossil Free campaign on U.S. college campuses. Within months, the campaign spread to hundreds of schools, including Boston College, Fordham University, Georgetown University and Seattle University. But not Dayton, where the question of divestment began with the board.

Two central questions were raised from the start: What constitutes fossil fuel divestment? And what is the endowment's exposure to those companies?

To the first question, the investment committee decided to focus on companies directly involved in the mining, extracting and refining of coal, oil and natural gas. That led to two lists: the Carbon Underground 200, the top-100 coal and top-100 oil and gas publicly traded companies with the largest fossil fuel reserves; and the Filthy 15 — what Dayton referred to by the less-loaded Fossil Fuel 15 — composed of what climate activists consider the "largest and dirtiest" U.S. coal companies.

As for the question of exposure, an analysis determined about 5%, or $34 million to $35 million, of its total investment pool, was invested in those companies, mostly in the endowment.

But the early deliberations weren't centered just on dollars and cents. How divestment tied into the university's mission was also a key element.

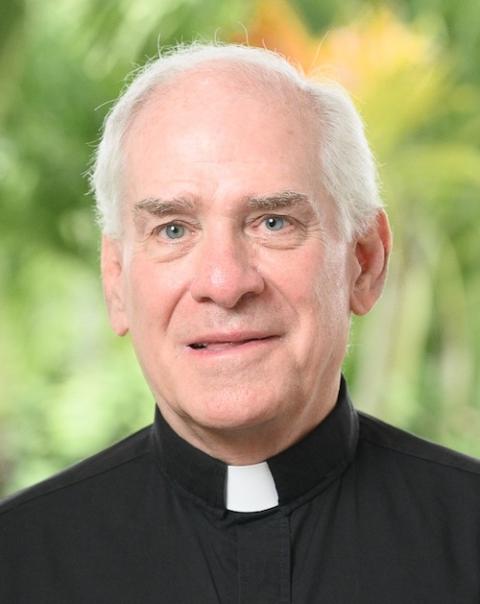

Marinist Fr. Martin Solma (University of Dayton)

Helping bring in that aspect were the Marianists themselves, a number of whom sit on the board. One of them was Fr. Martin Solma. As provincial of the U.S. Marianist province (2010-2018), he also held the role of vice chair of Dayton's board.

Solma, a Dayton graduate himself, joined the investment committee after the divestment question was raised. He recalled there was "a real openness to it" among the committee. Along with financials, the committee examined past statements on the environment from the U.S. bishops and consulted with the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities. They considered values like leadership and service, along with the university's commitments to human rights, environmental stewardship and sustainability, and the moral imperative to act on climate change.

While word of a papal encyclical on the environment was just beginning to surface, the committee reviewed comments from Francis on care for the environment in speeches and statements, including his 2014 World Day of Peace Message — the first of his papacy.

In that message, Francis said humanity is called to exercise "responsible stewardship" of nature, "by wisely using resources for the benefit of all, with respect for the beauty, finality and usefulness of every living being and its place in the ecosystem. … Yet so often we are driven by greed and by the arrogance of dominion, possession, manipulation and exploitation; we do not preserve nature; nor do we respect it or consider it a gracious gift which we must care for and set at the service of our brothers and sisters, including future generations."

"I think that influenced people," Solma said of the pope's peace message.

Advertisement

By the time Solma joined the committee, the discussion focused squarely on returns. A significant portion of the endowment funds student scholarships and other activities, so any potential negative impacts could jeopardize the future of both the school and its students.

"The real question was would the returns on our investments be comparable if we were to divest from fossil fuels, or what would the impact be on the investment?" he told EarthBeat.

To find an answer, the committee tapped several outside consultants, including RBC Wealth Management and the Chicago-based firm DiMeo Schneider, which served as the university's investment managers. The firm worked with the committee to model investment protocols without fossil fuels that would yield a comparable return. Over the course of a year of study, the committee examined other risks, as well. For instance, would divestment make its investment portfolio more volatile? They discussed at length the future value of fossil fuel stocks, amid global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

"We kept wrestling, can we do this? Can we do this well? And can we do it in a way that it doesn't impact negatively on the future of the university financially?" Solma said.

On the volatility question, Curran told NCR in 2014 that the university's low exposure to fossil fuels alleviated much of the concern. The committee, he added, felt comfortable if as much as one-third of the endowment was divested from fossil fuels, believing they could find suitable replacement investments. The committee also considered holding onto investments for the purpose of shareholder advocacy, but ultimately were skeptical of the impact it could have or what voice they could wield with the relatively small portion of shares.

In May 2014, the investment committee met a final time before the meeting of the full board of trustees. There, they received final presentations from DiMeio Schneider representatives, and made the decision to recommend full fossil fuel divestment.

"We hit a point where everyone at the table felt comfortable and accepted that as a Catholic institution this is a step we would take and realized that we would be out front of this issue," Curran told NCR after the decision was announced.

The next day, the full board voted unanimously to approve a new investment policy that would fully divest Dayton from the fossil fuel industry, prioritize investments in green and sustainable technologies, and restrict future investments that support fossil fuels or significant carbon-producing holdings.

A University of Dayton student works in the Lincoln Hill Gardens, an initiative of its Hanley Sustainability Institute to transform part of a previously vacant 5-acre site into an urban farm and community green space to increase access to healthy foods and offer open space for community gatherings and nature play. (University of Dayton)

The execution

Deciding to divest was only the first step. Now Dayton had to actually do it.

That role fell mostly to DiMeo Schneider as the outsourced chief investment officer, which managed the transactions and trades that would transition the portfolio according to the new investment policy. Working with them was Andy Horner, who came on board in January 2015 as Dayton's vice president for finance and administrative services. In that role, Horner also serves as chief financial officer, and he worked as a liaison between DiMeio Schneider and several board committees.

The process to fully divest the endowment from fossil fuels took upwards of two years, Horner told EarthBeat.

"You can't just flip a switch," he said.

The first step was divesting targeted fossil fuel holdings in domestic equity accounts. That was relatively simple compared to the more complicated, time-consuming untangling of Dayton's international holdings. For instance, some types of investments had multi-year timelines related to capital, Horner said. At the same time, the endowment had to adhere to overall asset allocation goals — the portfolio's balance of stocks, bonds, private equity and hedge funds — and avoid going off-balance or becoming exposed to undue risks.

Andy Horner (University of Dayton)

To make the changes, Dayton worked with a mix of existing and new managers, in many cases creating a custom portfolio specifically geared to its investment policy — an option made possible because of the endowment's size, Horner said. They also worked with managers to replicate the S&P 500 from a risk-and-return standpoint that screened out the assets, securities and equities identified by the new investment policy.

Over time, Dayton's investment managers evolved from relying on the Carbon Underground 200 and Fossil Fuel 15 lists and adopted the use of new, more advanced financial adviser tool sets for socially responsible investing, such as ones produced by Morgan Stanley Capital International.

"We used these two lists, and now we use actual tools that look at the actual individual companies and help us make quantitative decisions about whether they should be, based on our policy, whether they should actually be screened out of our portfolio or not," Horner said.

The use of new financial tools has not led to significant changes in the 2014 policy, he added, noting that any adjustments have been marginal. Nor has the scope for fossil fuel divestment really moved beyond the companies it first identified. What the new policy did do was direct investments to explore green and sustainable technologies. A series of principles developed by Dayton, titled "Catholic Sustainable Responsible Investing," directed its investments to seek out managers and companies consistent with Catholic social teaching, including technology in sustainable energy. Those green investments still had to meet the same risk-and-return criteria as any other security.

The new policy did not dictate a specific quota or percentage for these companies within the endowment, Horner said.

"I wouldn't say [we] divested $10 million here and we intentionally put $10 million in a green bond. We didn't do that," he said.

In a 2019 filing with the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE), Dayton self-reported it had invested more than $60 million in sustainability measures and companies with excellent environmental performances, including $1.3 million in renewable energy projects. Together, the investments represented roughly 7% of its total investment pool of $837 million.

The complexity of untethering certain funds made it difficult to pinpoint an exact date when Dayton could declare they were fully divested from fossil fuels. But by the end of 2016, Horner said the view was its endowment was materially consistent with the 2014 investment policy.

The University of Dayton removed half the lights in Roesch Library and upgraded the others to high-efficient double-life lamps and electronic ballasts, cutting energy use by half with a barely noticeable reduction in light output. (University of Dayton)

The fallout

When Dayton publicly announced its decision to divest on June 23, 2014, the response was primarily approving.

"The University is looking beyond its bottom line … by seeing the common good of all of humanity and especially the poor at home and abroad who are already feeling the impacts of a changing climate," Dan Misleh, executive director of Catholic Climate Covenant, said at the time. He called Dayton's new policy a "smart approach": not just divesting but reinvesting in renewables.

In a press release put out by the university, Michael Galligan-Stierle, then-president of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, applauded Dayton "as perhaps the first U.S. Catholic university to divest from fossil fuels."

"This is a complex issue, but Catholic higher education was founded to examine culture and find ways to advance the common good. Here is one way to lead as a good steward of God's creation," he said.

Students, especially those in the Sustainability Club, celebrated as well. A column in the student-run Flyer News called divestment "a bold move that will affect future generations in a positive way. This is a simple case of a university standing behind the values they try to teach."

In the time since, more than 180 Catholic institutions worldwide have publicly committed to fossil fuel divestment. That includes Seattle University in Washington and Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. In Nebraska, Creighton University announced in February it was divesting a portion of its endowment. In May, the Vatican told NCR it does not hold investments in the fossil fuel sector, though mostly as a result of its overall financial strategy.

Horner said in general the response has been supportive. "But I wouldn't be honest with you if I told you universally everybody said we completely agree."

Critics of the move argued that not investing in a sector of the market goes against a total return strategy and would put Dayton at a disadvantage.

A former board member made that case to Solma, the past Marianist provincial. A donor who worked in the fossil fuel industry told Solma and Curran in another conversation he felt the decision was a moral judgment on his life's work. Solma said he stressed that was not the intended message, but explained the environment is a moral issue and "we have to change the way we're living, and we have to change an economy that is built so heavily on fossil fuels."

Fossil fuel divestment is 'a bold move that will affect future generations in a positive way. This is a simple case of a university standing behind the values they try to teach.'

—University of Dayton student paper, Flyer News

The release in June 2015 of Laudato Si' — where Francis spelled out the need for a rapid, global transition from fossil fuels — reinforced to leaders at Dayton that their decision had strong moral standing. Whether it was the sound financial move would require more time.

Six years later, Dayton's endowment looks much like it did before divestment.

"Ultimately, it has performed generally very much like a non-divested portfolio. And that's been our goal all along," Horner said.

The market value of Dayton's endowment — which along with unrestricted reserves makes up the total long-term investment pool — has grown 18% since 2014, according to data compiled by the National Association of College and University Business Officers. Along with investment gains and losses, the market value is based on withdrawals, investment fees and donor gifts. In addition, the year-to-year percentage change in Dayton's endowment market value growth has remained largely consistent with the average performance across all reporting universities, and has stayed mostly on par with other Catholic universities in the Midwest.

A study published in January in the New York University Journal of Law and Business provided additional support for divestment having no noticeable impact on Dayton's endowment. The study pitted Dayton's actual endowment market growth against a synthetic, "Frankenstein" model that simulated the growth if it had not divested from fossil fuels. The results showed the two closely mirroring each other, with the real Dayton endowment showing slight improvement over the synthetic version.

"We feel confident in saying that University of Dayton is arguably better, marginally so, but arguably better than if it hadn't divested," said Christopher Ryan, co-author of the paper and an associate law professor at Roger Williams University School of Law who studies trust law and university endowments.

In 2009, the University of Dayton put in place a composting program. It diverts more than 200 tons of recyclable and compost material from landfills annually. (University of Dayton)

Overall, the study found no discernible consequences, positively or negatively, for endowment values of the 35 partially or fully divesting U.S. universities it examined. Ryan said part of that is because universities tend to be under-invested in the securities sector generally — and the fossil fuel sector specifically, representing 3% to 4% of an average university endowment — compared to the wider market, so the impact of such a move is blunted.

"I think a lot of [universities] are hesitant because they think that divestment will actually hurt the endowment, and our paper says not so fast," Ryan said.

While confident that Dayton would make the same move today, Solma said the fact it hasn't negatively impacted the endowment makes that an easier question to answer.

"If we had made this decision, and the endowment had really tanked, oh my goodness," said Solma, now a chaplain and special assistant to the president at Chaminade University in Honolulu. "We would have still made a statement, but we would have suffered for it. And maybe that's okay, too."

The decades Solma spent in East Africa and India put him face-to-face with the negative repercussions of development decisions by multinational corporations upon people who live in poverty and lack access to goods people in the West take for granted. As much as divestment was a statement to others, it was equally a message to Dayton itself, he said, and a commitment by the campus to the moral importance of conserving creation.

"If we're going to divest from fossil fuels, it means that the issue of the environment on the campus of the University of Dayton was a top priority," Solma said.

Following the divestment announcement, Dayton opened later in 2014 the Hanley Sustainability Institute, which has led sustainability efforts on campus. In November 2015, the institute hosted a conference on divesting and investing in light of Laudato Si'.

Last year, the university added undergraduate degrees in sustainability, to go along with existing minor and graduate certificates, and installed a 1.2-megawatt solar array. For years, students have conducted energy audits in the student residences.

Dayton has received a gold rating with AASHE's Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) program, made Sierra Club's Top-20 Cool Schools list, and, in 2019, updated its campus commitments to lowering greenhouse gas emissions. That same year, the Marianists finalized a conservation easement to protect 62 acres of land at their Mount St. John property outside Dayton.

When asked what advice he would give to other Catholic institutions considering their financial ties to fossil fuels, Solma was succinct.

"Be careful. Get good advice. And get managers who really know what they're doing."

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]