Isidoro Jajoy, a shaman from Colombia's Inga tribe, blesses people in Bogota Aug. 14 during a preparatory meeting for the October Synod of Bishops for the Amazon. (CNS/Manuel Rueda)

The upcoming synod on the pan-Amazon region, a broad geographic area ranging over a number of South American countries, will deal with three themes that have been consistent concerns of Pope Francis: the environment, the plight of indigenous peoples, and the need to provide effective pastoral care in local churches.

The October event also highlights Francis' use of the synod of bishops, a signature feature of this pontificate and one of the principal institutional fruits of the Second Vatican Council, as a means of advancing his program of reform.

This synodal assembly will also be the first during his papacy to focus on a particular region, in this instance it is the Amazon basin, including territory belonging to Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guyana.

The synod of bishops was first established by Pope Paul VI, at the request of the council. At Vatican II, a number of bishops, inspired by the practice of the Eastern Catholic Churches, had called for the creation of a permanent synod of bishops as an expression of the council's teaching on episcopal collegiality. They envisioned a standing synod exercising deliberative authority and sharing with the pope the exercise of pastoral leadership of the universal church.*

When Paul established the synod of bishops in 1965, he did create a permanent synod, but not a standing synod. Rather, the pope created a synod that would only intermittently be in assembly and would have only consultative authority. These synodal assemblies would take one of three forms: an ordinary general assembly that met every three to four years; an extraordinary general assembly convened whenever a matter of urgent concern commended it; and a special assembly that focused on the pastoral concerns of a particular geographic region.

Advertisement

For much of the post-conciliar period, the subject matter addressed at these synodal assemblies was carefully monitored by Vatican officials. Controversial topics were often kept off the table. Synodal procedures discouraged free-flowing conversation among participants. After 1971, all subsequent synods would yield the right to publish their own final statement, deferring to the pope the responsibility for promulgating a post-synodal document. Many of these documents, known as apostolic exhortations, made considerable contributions to the development of Catholic teaching — e.g.: Paul VI's Evangelii nuntiandi (1975), Pope John Paul II's Catechesi Tradendae (1979), Familiaris Consortio (1981) and Christifideles Laici (1987), and Pope Benedict XVI's Verbum Domini (2010). Benedict made some modest revisions to the synodal procedures, offering more opportunity for open conversation.

It is with Francis, however, that the synod of bishops has been transformed from a well-orchestrated and carefully censored ecclesiastical showpiece to the principal instrument for the implementation of his reformist agenda. Beginning with preparations for the extraordinary synod on the family, the pope called for widespread consultation of the whole people of God, including the broad (if uneven) distribution of a questionnaire on matters related to the family. He revised the synodal procedures to allow for a much more open conversation and explicitly exhorted the synodal participants to exercise parrhesia, to speak boldly and without fear of instigating disagreement. He made sure that controversial topics, like the status of LGBTQ persons, would not be excluded from consideration.

Indeed, over the past six and half years, a clear pattern has emerged. As Francis has met resistance to his efforts at curial reform (we are still awaiting his apostolic consitution on curial reform), he has often chosen to redirect the flow of pastoral discernment and decision-making. Where previous popes remanded key ecclesial and pastoral issues to the appropriate Roman dicastery for study, usually resulting in the issuance of a curial notification or instruction, Francis has preferred to assign consideration of key issues to various synodal assemblies.

His rationale for this momentous shift was made clear in the fall of 2015 when he gave perhaps the most ecclesiologically significant address of his pontificate. While commemorating the 50th anniversary of the synod of bishops, the pope offered an astonishing theological reflection on the church as itself fundamentally synodal in nature. He called for a "listening church" attentive to the witness of the whole Christian faithful, the sensus fidelium, and demanded the establishment of consultative structures to be realized at every level of church life.

Finally, in September 2018, Francis promulgated the apostolic constitution, Episcopalis Communio, establishing new norms for the synod of bishops, norms more in keeping with his commitment to ecclesial synodality.

This brings us to the upcoming pan-Amazonian synod. This regional synod combines Francis' commitment to synodality with another key principle of his pontificate, ecclesial subsidiarity. That principle holds that ecclesial issues are best dealt with at the local level, with "higher authority" intervening only when the good of the universal church requires it.

Fires burning in the Amazon rainforest are pictured from space by the geostationary weather satellite GOES-16 Aug. 21. (CNS/Reuters/NASA, NOAA)

But why focus on this remote region in South America? The first reason was indicated in the pope's encyclical, "Laudato Si', On Care for Our Common Home." There the pope indicated the global importance of the Amazon basin as one of the two lungs through which our planet must breathe. In this encyclical, he also denounced the devastating deforestation policies of key countries in the region. Second, for a pope outspoken in his concern for the rights of indigenous peoples, this synod would draw global attention to a region that has seen indigenous peoples robbed of both their land and their right to self-determination. These peoples have often been victims of drug and human trafficking. Moreover, there are more than 100 indigenous communities in that region that are "voluntarily isolated" from the larger world; their fragile existence is now under threat. Francis is committed to a polyhedral vision of both church and society, where genuine cultural differences do not threaten but rather enrich an authentic global consciousness.

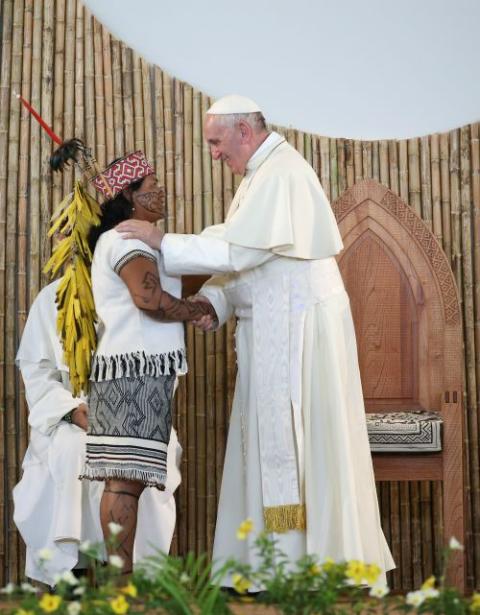

Pope Francis is greeted by a member of an indigenous group from the Amazon region during a meeting at the Coliseo Regional Madre de Dios in Puerto Maldonado, Peru, Jan. 19, 2018. (CNS/Reuters/Alessandro Bianchi)

Finally, Catholics in that region are facing a dire challenge to their sacramental life as the priest-to-Catholic-persons ratio, in some sub-regions, is as high as 1:16,000. It is this situation that led the instrumentum laboris, the working document prepared in advance of the synod, to raise the possibility of the ordination of viri probati, that is, mature married males, to the priesthood. At the same time, the document calls for the establishment of new ministries better suited to the needs of the local churches in the region. It specifically acknowledges the many charisms of women in the church and calls for their greater inclusion in church leadership. This last point has led some to wonder whether the question of women deacons might also be raised.

The likely discussion of new ministerial needs in the Amazon church further reinforces the pope's commitment to subsidiarity, or "decentralization." He is not inclined to propose sweeping solutions to pastoral problems from the distant vantage point of the Vatican; he prefers local churches to address these issues on their own and, when necessary, to seek permission from Rome for creative implementation of local solutions.

For many U.S. Catholics, the upcoming synod may seem to have little relevance. Yet we cannot ignore the fact that the attention the synod is expected to give to climate change, the rights of migrants and displaced people and opportunity for regional innovation in key aspects of pastoral practice, all challenge the agenda of a well-financed Catholic right that has persistently opposed Francis. This vocal minority has wedded a dangerous Catholic integralism that resists* necessary pastoral innovation and legitimate doctrinal development with a Trumpian repudiation of climate change science and the rights of migrants and refugees. This synod could help the North American church repudiate the agenda of the vocal anti-Francis camp reminding us that the only way out of the scandalous quagmire in which our church finds itself lies in the humble, missionary vision of this South American pope.

* Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct two copy editing errors. In paragraph four, the author is referring to Vatican II, not Vatican I. In the final paragraph, the words "that resists" were missing.

[Richard R. Gaillardetz is the Joseph Professor of Catholic Systematic Theology at Boston College.]