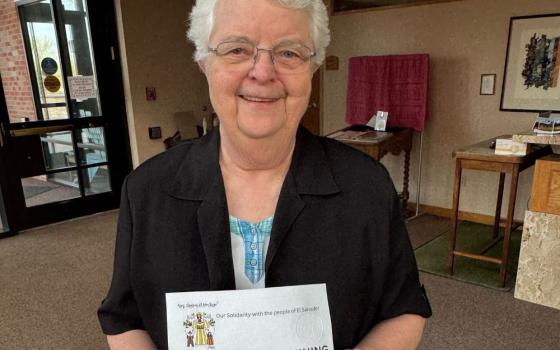

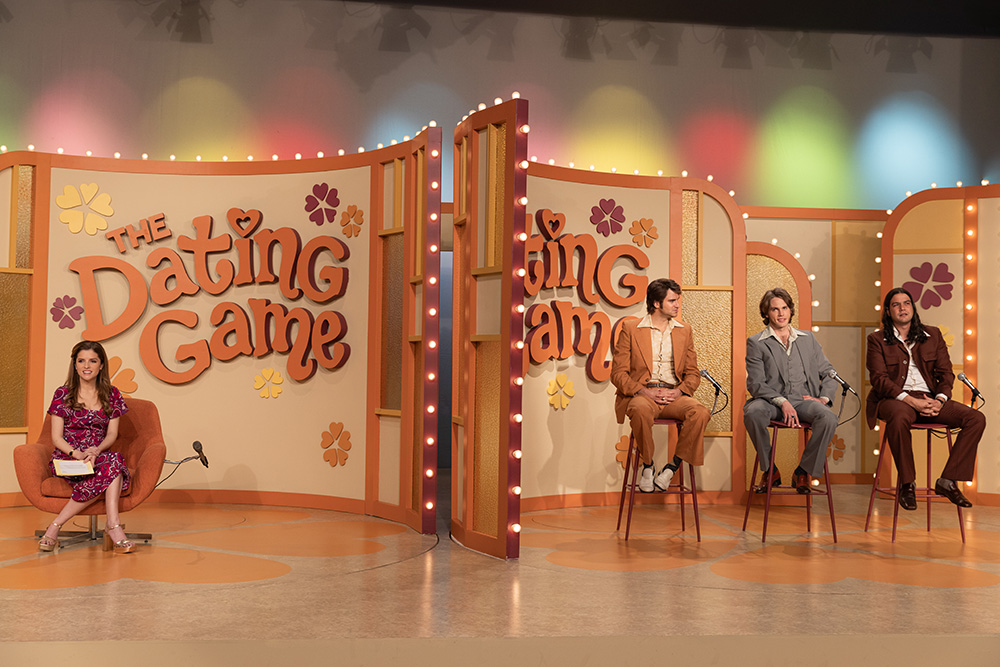

Actress Anna Kendrick, left, makes her directorial debut in the new Netflix film "Woman of the Hour," which tells the improbable but true story of a serial killer who appeared on a national dating show seeking his next victim in 1978. (Netflix/Leah Gallo)

Earlier this year, a social media debate raged over a simple question posed to women: Would you rather be alone in the woods with a man or a bear? Many women chose the bear. And this made some men very angry.

On "The Graham Norton Show" Oct. 25, actress Saoirse Ronan found herself on an otherwise all-male interview panel. When the topic turned to the absurdity of taking out one's phone as a defense against violence, Ronan, who had frequently been spoken over during the conversation, silenced everyone by saying, "That's what girls have to think about all the time." The clip went viral, sparking many conversations about the phone calls women fake when they feel unsafe in public.

Had there been cellphones in 1978, Sheryl Bradshaw, played by Anna Kendrick in the new Netflix film "Woman of the Hour," would surely have pulled hers out as she was followed across a dark and empty parking lot by a dangerous man. Kendrick's directorial debut tells the improbable but very true story of Rodney Alcala, a serial killer of women and girls, who appeared on a national dating show seeking his next victim.

Interspersed with scenes of the young women Alcala tortured and killed before and after appearing on the show, we are introduced to Kendrick's Bradshaw, an aspiring actress with a degree from Columbia who is having trouble breaking into the LA scene. Reluctantly, she acquiesces to her agent's urging that she appear on the dating show for exposure.

Bradshaw is clearly repulsed by the innuendo-heavy banter the dating show encourages, and, with a bit of permission from a female makeup artist during a commercial break, she decides to rewrite the questions she asks her suitors; she decides to be herself. Assertive, confident and intelligent, Bradshaw disarms her suitors with questions that reference Kant and Einstein. Pointedly and without elaboration, she asks them, "What are girls for?"

Advertisement

When the angry host cuts the show short, Bradshaw nervously asks the female staff, "Did I go too far?"

The women, employed by the show for years, share an acute observation: The questions a female contestant asks the suitors really all boil down to the same thing. Which one of you will hurt me?

Bradshaw's encounter with Daniel Zovatto's initially charming but increasingly terrifying Alcala will ring true for many women who have felt danger arise like steam from a boiling kettle in the company of a man they had thought was safe. But as brilliantly as the film depicts this suspenseful encounter and the terror of Alcala's victims, its greatest strength is its straightforward presentation of how dangerous it is to be a woman in the everyday world.

"Woman of the Hour" is an unflinching portrait of the dedicated effort women must make to minimize themselves, assuage men's discomfort and defuse their anger, knowing all too well that violence could be an outcome regardless.

Nervous laughter and uncomfortable smiles feature heavily among Alacala's victims — and in Bradshaw's scenes as well, be they with male directors denigrating her performance at an audition, a pushy neighbor whose advances are unwelcome or the misogynist host of the dating show (convincingly played by Tony Hale).

Multiple times, Bradshaw is nonconsensually touched, and her micro-expressions in these situations are a work of art, communicating first her discomfort, then her immediate realization that it is her responsibility to mitigate the blow to the man's ego, to calm his anger before it is too late. To say that she does not want to be touched, that she is not interested in a date, is simply too dangerous.

Anna Kendrick as Sheryl Bradshaw and Daniel Zovatto as serial killer Rodney Alcala in "Woman of the Hour" (Netflix/Leah Gallo)

Again and again, we watch Bradshaw find herself with no choice but to play along until she has an opening to make her escape.

I'm not alone in wishing we'd left all this terror behind as a society, but any woman will tell you that we have not. I have been catcalled, followed, groped and, to my sorrow, I am sure you have had these experiences as well, or know a woman who has.

With a now re-elected president who has been found liable for sexual abuse in a civil trial, our country has shown how very much we are willing to sweep under the rug at women's expense.

With Catholic leaders who have again and again declined to meaningfully respond to the global request for women's leadership, keeping even its committee discussing the question under an opaque blanket, our church has shown that we have not yet arrived at a place where women can be their full selves, offering their God-given gifts and service to others.

The institutional response to advocacy for women's ordination to the priesthood and the diaconate sometimes makes me anxious about potential pushback. Like Bradshaw, I have worried about the risk inherent to angering powerful men.

On Bradshaw's chilling date with Alcala, she explains that she only agreed to go on the dating show for career exposure, to be seen.

"And did you feel seen?" Alcala asks, with thinly disguised malice.

"I felt looked at," Bradshaw replies.

Oh, to live in a world and be part of a church that doesn't just look at women, but empowers women to be their fullest selves — without fear of retribution for it.