(Dean Rohrer)

There may have been a time when moving from a point of indecision on the matter of climate change, to a decision on whether it is real and caused by humans or not, required leaps of faith of somewhat equal proportions. But that was a long time and a lot of science ago.

The science, as it has developed, may not be perfect, but it is long past time that the question turn from whether human activity is causing climate change to what do we do about it. The Catholic church should become a major player in educating the public to the scientific data and in motivating people to act for change.

The case for the reality of human-caused climate change was made in the strongest terms to date in the recently released third National Climate Assessment, a report exhaustive in its detail and the manner of its preparation. It was compiled by a team of more than 300 experts, including policymakers, decision-makers from the public and private realms, researchers, representatives of business and nongovernmental organizations, as well as representatives of the general public.

It was reviewed extensively, including by a panel of the National Academy of Sciences, the 13 federal agencies of the U.S. Global Change Research Program, and the federal Committee on Environment, Natural Resources, and Sustainability.

As columnist Michael Gerson wrote of suspicions that the rising awareness of climate change was a product of scientific fraud: "In this case the conspiracy would need to encompass the national academies of more than two dozen countries, including the United States." The larger point he makes is that we need to get on with the questions that only science can address.

The National Climate Assessment report doesn't speak of the crisis as a moment to anticipate but as increasingly evident today. The most frightening point is that climate change "is projected to continue, and it will accelerate significantly if global emissions of heat-trapping gases continue to increase." Those changes, in turn, will increasingly threaten humans "through more extreme weather events and wildfire, decreased air quality, and diseases transmitted by insects, food, and water."

In an opportune coincidence, about the same time the U.S. government was releasing the National Climate Assessment, the Vatican was releasing a far shorter summary of its five-day summit on "Sustainable Humanity, Sustainable Nature: Our Responsibility."

While the church has taken it on the chin for centuries-old condemnations of scientific truths, the reality today is that it stands uniquely in a position to not only aid the science but also to engage in the ethical discussions essential to any consideration of global warming.

If there is a certain wisdom in the pro-life assertion that other rights become meaningless if the right to life is not upheld, then it is reasonable to assert that the right to life has little meaning if the earth is destroyed to the point where life becomes unsustainable.

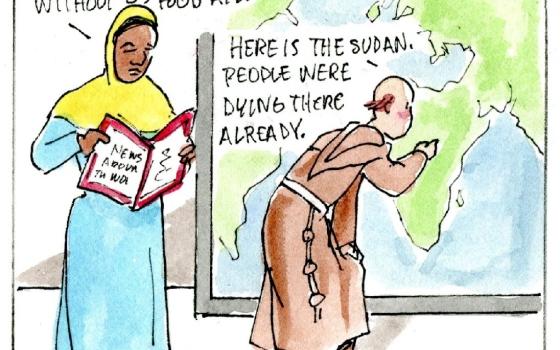

Cardinal Oscar Andres Rodríguez Maradiaga described the problem during a talk opening the Vatican conference. He described nature as neither separate from nor against humanity, but rather existing with humans. "No sin is more heartless than our blindness to the value of all that surrounds us and our persistence in using it at the wrong time and abusing it at all times."

Humans, he said, have become technological giants while remaining ethical children.

Humans have been driven to a point of decision by the consequences -- good and bad -- of two centuries of technological development. In his closing remarks at the Rome meeting, NewYork Times writer Andrew C. Revkin stated, "Scientific knowledge reveals options. Values determine choices.

"That is why the Roman Catholic church -- with its global reach, the ethical framework in its social justice teachings and, as with all great religions, the ability to reach hearts as well as minds -- can play a valuable role in this consequential century."

The problem is enormous, but so is the opportunity for the church to use its resources, its access to some of the best experts in its academies and the attention of those in its parochial structures to begin to educate. This is a human life issue of enormous proportions, and one in which the young should be fully engaged. The Climate Assessment document as well as the recent discussion at the Vatican are excellent starting points for developing curricula materials for education programs in parishes and schools.

Catholic high schools and colleges have the freedom to explore these vital issues from both the scientific and ethical perspectives. They can bring theological perspectives to bear on the issues. Educators and students could devise ways to become active at all levels, from homes, to communities, to states, to advocating for legal measures to offset the effects of global warming.

Finding a fix for climate change and its potentially disastrous consequences, particularly for the global poor, is not the work of a single discipline or a single group or a single political strategy. Its solution lies as much in people of faith as in scientific data, as much or more in a love for God's creation as it does in our instinct for self-preservation.