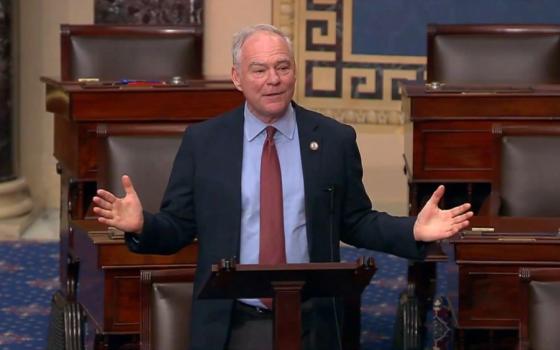

El Salvador President Salvador Sánchez Cerén, second from left, meets Gov. Carlos Padilla, second from right. Third from right is the writer, Andés McKinley. (Provided photo)

There are times in life when things come together, forces galvanize, pieces fall into place and processes take on a magical quality that keeps you wondering when the dream will end. That's what it felt like for those of us in the struggle against metallic mining, when legislators here finally found the political will to block an industry that threatened to rob this country of its future.

It was the most amazing week in the 12-year history of our struggle. And we owe much of the magic to the governor of a province called Nueva Vizcaya in the Philippines, on the other side of the world.

El Salvador and the Philippines have several things in common. Both are located on the rim of the Pacific Ocean, both suffered the consequences of Spanish colonization (the Philippines endured U.S. colonization as well), and both have been brutally victimized by an Australian mining company called OceanaGold.

For the past 12 years, Salvadoran communities, social organizations, academic institutions and other key actors have been engaged in a battle to protect the environment, promote sustainable livelihoods and defend national sovereignty against companies like OceanaGold, which wanted to mine gold and silver in the country's most important watersheds.

The underlying reason for the long and radical resistance to metallic mining is the threat this industry represents to El Salvador's natural resources, especially water, which are already suffering from dramatic levels of deterioration and vulnerability.

According to the United Nations, El Salvador has, after Haiti, the most deteriorated environment in the Western Hemisphere. It is the most deforested country in Latin America, with as low as 1 percent of its original forests intact. Over 90 percent of its surface waters are contaminated, and it has the lowest level of available freshwater per capita in Central America. According to the Global Water Partnership, the country also suffers from a clear trend toward water stress, a situation in which freshwater supplies become inadequate to respond to demand.

This dramatic level of environmental vulnerability explains why almost 80 percent of the population is opposed to metallic mining, and 77 percent has demanded that the government take immediate measures to close the door to this industry, according to surveys by Central American University José Simeón Cañas.

It was in this context that the university began, two years ago, to develop a proposal for a bill prohibiting metallic mining. After a lengthy process of consultations with civil society organizations and other key actors, the bill was presented to the Legislative Assembly by an alliance of Central American University, the San Salvador Archdiocese and Caritas on Feb. 6 of this year. It was passed into law on March 29.

In the days leading up to this historic victory, the university planned a "Week of Action Against Metallic Mining." It included press conferences, TV and radio interviews, public forums, presentations to key decision-makers, a meeting with President Salvador Sánchez Cerén and — confident of our incipient victory — a celebration at the close of the week with the rural communities most threatened by mining.

El Salvador had been the victim of an increasingly aggressive campaign by OceanaGold. It promoted the myth of "responsible mining," and claimed that its activities in the Philippines were a model for mining with "zero risk to the environment." As part of our strategy to unmask this myth and the company's persistent lies, the university invited the governor of Nueva Vizcaya to come to El Salvador and participate in our Week of Action.

Gov. Carlos Padilla served his country for 29 years as a member of Congress and, for six years, was assistant speaker of the House. Now, as governor, he is involved in a fierce battle to protect the environment, especially water, in a province known for its natural beauty and for the production of rice and citrus fruits.

OceanaGold has a major gold and copper mine in the village of Didipio in Nueva Vizcaya. In meeting after meeting during our Week of Action, the governor described what had happened in the Philippines:

- The primarily indigenous population had been forcibly displaced by OceanaGold, and 187 homes had been bulldozed and burned in the process.

- In 2011, the human rights ombudsperson called on the central government to suspend OceanaGold's permit to mine, and was refused.

- Two anti-mining activists were killed in 2012 under circumstances similar to those in which five activists were assassinated in Cabañas province in El Salvador.

- In 2017, the new government of the Philippines had finally suspended the mining permit of OceanaGold due to the enormous environmental destruction its project had caused.

Padilla is a quiet man, slight of build and unimposing, but his voice gets deeper and his message gets stronger when his emotions are stirred, and they were stirred each time he began talking about OceanaGold in the Philippines. The governor, accompanied by his provincial commissioner for environmental planning, Edgardo Sabado, addressed both general audiences and key policymakers. Padilla demonstrated with visual images and documented facts the environmental destruction and the violation of basic human rights that have occurred in his country, and that El Salvador could avoid by banning metallic mining. The Salvadoran audiences fell in love with him.

On the day the Salvadoran law was finally approved, the governor's name and testimony were mentioned several times by legislators who, it was obvious, had been touched by him. Sánchez Cerén met with him for over an hour, clearly enthralled with the message and the style of this special human being who had come from the other side of the planet in solidarity with El Salvador.

Time and again during his visit, Padilla told me how pleased he was to be part of this historic moment and of our victory. Surely, he took back home important lessons from our struggle, but he also left us amazing gifts: his knowledge, his wisdom, his solidarity and his contagious affection. He was the centerpiece of the most amazing and magical week I can remember in 12 long years of arduous struggle. It was a brief moment in time, more precious than gold.

[Andrés McKinley is a specialist in water and mining at Central American University José Simeón Cañas. He has worked on development issues in Central America since 1977.]