George Wiegel penned an essay recently entitled “To See Things as They Are,” and he really got me going. Early in his essay, he unleashes this paragraph that made me think Weigel was going to shed his narrow neo-con vision and embrace Pope Francis. Weigel wrote:

Answering the question about the Church’s relationship to the civil order, at any moment in history, requires us to begin with ecclesiology and to remember that the Church’s first obligation is to be the Church: the communio that witnesses to the Resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ and the in-breaking of the kingdom of God, here and now. Those who witness to these truths “see” the world differently than others. In the image that C. Kavin Rowe uses for the title of his brilliant explication of Acts, the public confession of the lordship of the risen Christ creates what the world thinks of as a “world upside down,” but what Christians understand to be the world seen truly. By constantly reminding the world that salvation history is the interior, if you will, of world history, and that salvation history tells the world’s story in its full depth and against its most ample horizon, the Church does the best service it can do for the world, including that part of the world we call “public life.”

In the next paragraph, he cites the ur-text of Communio theology, Gaudium et Spes #22: “Christ the Lord . . . Christ the new Adam, [who] in the very revelation of the mystery of the Father and of his love, reveals man to himself and brings light to his most high calling.” And Weigel concludes his essay with a forceful call for preaching and catechesis that is rooted in the Bible, not in natural law, which might have been a case he would have made five or more years ago. It finally took, I thought. He gets it.

Nah. He was just joking. It turns out the Weigel’s version of Evangelical Catholicism is not a Catholicism that is rooted in the Gospels, but a Catholicism that looks a lot like contemporary evangelicalism. The Gospels, you may recall, speak about the poor, and not incidentally. The Master announces His mission in the fourth chapter of the Gospel of Luke by saying He has come to preach good news to the poor. His parables tend to focus on the poor. The Beatitudes announce that the poor are blessed. Jesus not only attended to the poor, He was poor. Alas, Mr. Weigel does not once, not once, mention the poor in his essay.

Weigel does have an idea about how the Church should engage the culture. He writes, “First, as I argued at some length in Evangelical Catholicism, the Church must discipline its public witness by resisting the temptation to comment on virtually every contested issue of public policy and by focusing primary attention on two key issues: the life issues and religious freedom.” I am with him on the first one. The Church should continue to make a strong and consistent witness to life issues in the public square. The same Gospel that spends such considerable time on the poor is also a Gospel of Life, indeed, the central drama in the Gospel culminates with the triumph of life over death. And, in addition to our “throwaway culture’s” hellish attitude towards the unborn, that same culture also views the elderly and the infirm with increasing suspicion. After all, the elderly, viewed from the perspective of social services, are takers, not makers. Budget cutting zealots look at disbanding or privatizing Social Security with relish. And, along come some equally pernicious libertarians of the left, ready to offer euthanasia as a remedy for all that ails the elderly.

There is an additional reason I believe the Church’s witness on life issues in the public square makes sense: It is true to who we are and what we do. Think of the countless Catholic hospitals that care for the sick, save those whose lives are threatened, and, in their maternity wards, never forget that there are two patients to be cared for. Many of us are looking forward to the Holy Father’s encyclical on the environment in part because we recognize the dangers to human life posed by climate change, but those dangers are already making themselves felt in parts of the world where our Catholic brothers are sisters make their homes, and we can call attention to those threats not just with statistics but with personal stories. One of the ways you point out the need to evaluate public policies in terms of their effects on human beings is to humanize the issue. Think of Mrs. Vicki Kennedy powerful op-ed against physician-assisted suicide in the days before the referendum on that issue in Massachusetts in 2012. This holds true about why the Church should focus on the poor in our public witness: Think of the witness provided at countless state legislatures throughout the country by directors of Catholic Charities when budget cuts threaten to undo the social safety net or the USCCB’s efforts to create a “Circle of Protection” around programs that assist the poor when sequestration threatened those programs.

I am not sure Mr. Weigel’s case for making religious liberty a central concern is very persuasive. I have searched the Scriptures and do not find much in the way of discussion about the issue. Furthermore, if this issue is to be a central focus of our public witness, that witness will largely be conducted by lawyers and I do not think that Church as litigator is the best path towards evangelization. There is also the little problem that the issue has been so highly politicized, often by conservative legal scholars with many axes to grind, I fear the Church’s leaders have already gotten too far out on the limb: Yes, we should defend the integrity of our Catholic ministries, but arguing that conscience rights trump virtually any and all pieces of legislation seems to me to be a bridge too far and a bridge many of us would be reluctant to cross even if it were closer.

Mr. Weigel has a good section about freedom as willfulness. He writes: “I’d like to suggest that, inter alia, it comes down to Ockham’s Triumph: the de facto ‘establishment’ in American public life of the notion that freedom is willfulness, and that willfulness can attach itself to any object, ‘so long as no one gets hurt’ (which ‘no one’ obviously does not include the aborted unborn and the euthanized, simply underscoring the confusions of the age).” Of course, there is a rather fine example of freedom as willfulness at hand but, strangely, Mr. Weigel does not mention it. Our spread eagle capitalist consumer culture strikes me as the primary instance of freedom as willfulness in American culture today, except that it dismisses the one caveat at which Weigel sneers, and is all too willing to harm others in its ceaseless grasping after material profit.

For good measure, Weigel also thinks the leaders of the Church should prepare the faithful for a period of persecution. Fear is always a useful tool to whip up support. I think that Christians should always be prepared for persecution, to be sure, but it seems to me that the principal challenge to our public witness to the faith today comes not from Leviathan but from a materialist culture that offers shiny object after shiny object to keep everyone happy, all the while stripping us of any semblance of moral fiber and making the repeated calls from the Magisterium to a conversion of lifestyle, calls made even by Weigel’s hero Saint Pope John Paul II, from gaining any traction. We live in a society where some two-thirds of economic activity is based on consumption. That cannot be sustained economically, environmentally or morally. But, do not look to our neo-con friends to question the economic powers that be nor the economic theories that justify their rapacious behavior.

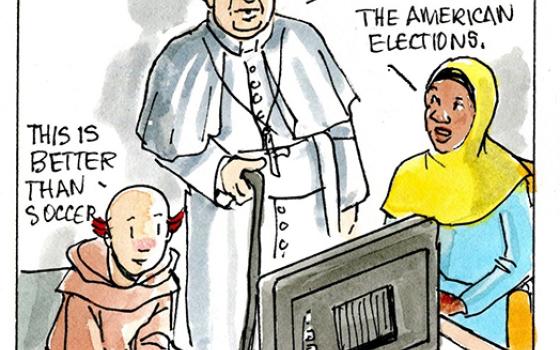

It is sad, really, that Weigel still seems intent on reducing religion to ethics, thence to politics and finally to legalisms. That is the antithesis of what Communio theology is all about. (It is also an essential part of Saint Pope John Paul II’s teaching that Weigel never really grasped.) But, sad or not, I have to ask myself a question. Why is Weigel’s column still the most widely syndicated in diocesan newspapers? He is not merely on a different page from Pope Francis, they are reading from different books. For all his talk about “evangelical Catholicism,” Weigel does not seem to realize that it is the pope who is giving an exemplary witness to a Catholic faith rooted in the Gospels. And the bishops who publish his work, giving it a kind of imprimatur, must ask themselves why they continue to disseminate his writings which are so out of sync with Pope Francis’ most recurrent themes. A poor Church for the poor. A Church that accompanies people. A humble Church. These are Pope Francis’ themes. They are not Mr. Weigel’s. Let him publish in First Things all he wants. That journal is well on its way to becoming the official organ of the opposition to Francis. But, if I were a bishop – and we can all be grateful I am not – I would not be publishing his neo-con nonsense in my diocesan newspaper.