Ross Douthat’s article in Atlantic sounded an alarm bell he has struck before, the idea that Pope Francis could provoke a schism if his revolutionary impulses turn out to be more than rhetorical devices or symbolic gestures. But, Douthat both underestimates the revolutionary quality of what is transpiring at the Vatican and overestimates the degree to which it might provoke a new schism of any size.

Take for example this paragraph. Douthat writes:

The Church is not yet in the grip of a revolution. The limits, theological and practical, on papal power are still present, and the man who was Jorge Bergoglio has not done anything that explicitly puts them to the test. But his moves and choices (and the media coverage thereof) have generated a revolutionary atmosphere around Catholicism. For the moment, at least, there is a sense that a new springtime has arrived for the Church’s progressives. And among some conservative Catholics, there is a feeling of uncertainty absent since the often-chaotic aftermath of the Second Vatican Council, in the 1960s and ’70s.

There is more than an “atmospheric” revolution afoot in the halls of the Vatican. When Douthat wrote these words he did not know that Bishop Robert Finn’s resignation was pending, and that resignation was profoundly consequential, and not just for the good people of Kansas City-St. Joseph. Bishops throughout the world have been put on notice that if they fail to follow their own procedures and protocols for handling allegations for child sex abuse by clergy, the Vatican will not necessarily stand by the bishop.

The deeper changes have to do with the very issues that Douthat is worried could prove an occasion for schism, issues relating to the synod on the family. I do not know what the forthcoming synod will decide. Will it simplify the procedures for procuring an annulment? Will it acknowledge that maybe we should not view a failed marriage as presumptively valid, as we do now? Will it take up and endorse the idea that Holy Communion should not be withheld from the divorced and remarried, not so much on account of any change, perceived or real, in the Church’s understanding of the sacrament of marriage but because of a renewed understanding of the sacrament of the Eucharist, that Holy Communion is not a prize for the perfect but medicine for the journey? Will the synod go whole hog and recognize that there is way too much hubris in our current theological claim that any person can present themselves for Holy Communion because he or she is “in a state of grace”?

I do not know the answers to these questions. Neither does Douthat. And – here is the critical point – neither does Pope Francis. As Vatican correspondent Gerard O’Connell wrote at America, this pope seems less focused on outcomes than he is on reinvigorating the processes by which the Church determines the outcomes. It is the rebirth of synodality, the abandoned step-child of the Second Vatican Council, that is the revolution here. And, it is taking the humdrum synod procedures of the past and investing them with genuine dialogue that further makes the change wrought by Pope Francis both revolutionary and difficult to predict.

Earlier this week, I also called attention to George Weigel’s tribute to the late Cardinal Francis George in which Weigel wrote, “The old post-conciliar battles are, largely, over, and the course has been set.” That judgment seems grossly premature. I am not fond of the term “battles” but the post-conciliar conclusions reached by Pope John Paul II, in which issues were taken off the table and questions were deemed inappropriate or worse, those conclusions may have satisfied conservative American Catholics, but they did not necessarily serve the Church’s vital mission of evangelization. So far from the repeatedly stated “need” to draw sharp boundaries between Catholic identity and the ambient culture, the still young pontificate of Pope Francis is more interested in building bridges than boundaries.

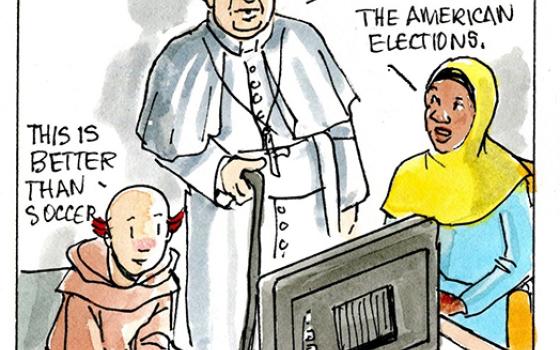

I suspect that Douthat is right that some conservatives will find the bridge building task unappealing. Their certainties will be shaken, then shelved. But, will there be a schism? As far as I can tell, the opposition to Pope Francis resides mostly among the commentariat and some high ranking Church personnel, both clerical and lay. The people in the pews, conservative or not, really like this pope. And, they like him for a reason. He speaks and acts in ways that are consistent with the Gospel we hear proclaimed at Mass and which we read in the quiet of our homes. In those Gospels, we do not read much about the issues that have defined the “post-conciliar battles” but we read a great deal about going to the poor and the marginalized with good news, about the stupendous, supernatural claims made by and about the person of Jesus, and about an early Church filled with zeal, holding all things in common, rigorous in their pursuit of all the virtues, not just those that pertain to our sexual appetites.

This essay, however, shows Douthat’s assessments of religious matters maturing. His analysis of the three biographies of Francis is largely on target, although I am more suspicious of the Vallely thesis that Bergoglio had any kind of conversion while he was in exile after being sacked as Jesuit provincial, and I am likewise more convinced that Pique’s biography shows important aspects of Bergoglio’s personality that are critical to understanding his papacy than can be found in the other two. Like Douthat, I found Ivereigh’s book deeply informative. What is more interesting, though, is that instead of being hostile as other conservative Catholic critics are, Douthat seems intrigued by Pope Francis. And, he utterly lacks the sense of lost entitlement and influence that stalks the analysis of certain other U.S. conservative Catholic writers. He can’t see his way clear to certain proposals, like communion for the divorced and remarried, but he is not as dismissive of the possibility that something genuinely Catholic is going on here, that this is not a bit of bad ecclesial weather during which good Catholics will hunker down and wait it out. Given the prime journalistic real estate Douthat has, I hope he continues to let his sense of intrigue trump his sense of the significance of syllogism: The Church in the U.S. needs thoughtful, informed conservative voices in the public square.