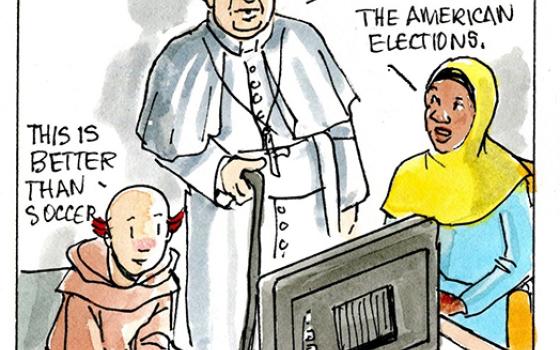

Pope Francis answers questions from journalists aboard his July 12 flight from Asuncion, Paraguay, to Rome. (CNS/Paul Haring)

On the plane ride back to Rome, Pope Francis said he had been told that he needs to spend some time talking about the middle class and not just the poor, especially in the context of his forthcoming visit to the United States. It will be interesting to see what he comes up with because it always is, but also because the very concept of the middle class seems to be losing its usefulness.

The middle class has always been a relative concept. I remember in the 1980s, a friend who had a job in the government making about $100,000 per year was thinking of moving to New York City. But, he explained, to live in New York the way he did in Washington, he would need to make more than twice that amount because everything was more expensive there, and some things, like transportation, were not even commensurate: In D.C., you can have a car to get you around with ease while in New York, you would need a driver to achieve the same degree of ease. I pointed out that there was an alternative: the subway. But of course, no part of the middle-class, or at least upper-middle-class, lifestyle includes public transportation. And, of course, those of us who are more or less in the middle class in the United States would be considered rich in many countries around the globe, including the three countries the pope just visited. Many millions of people do not get to calculate "ease" when making their life decisions.

The middle class was once differentiated from the working class by measures of education, which in turn resulted in higher wages, and still does. Except that today, more and more working- and lower-middle-class Americans are finding it harder and harder to even afford a good education. Even the upper middle class worries about the soaring cost of preschool, to say nothing of college. Many move to more expensive suburbs to access better public schools or sacrifice to pay for a good Catholic school.

Elizabeth Scalia recently wrote a column explaining that she feels the pope is always scolding her and those like her. Among her observations are these:

But sometimes, when I read Pope Francis exhorting us again about the poor, or the environment, and urging people once again, to take action, to go out into the world and fix-all-of-the-things, because Jesus wants it (and yes, I'm sure Jesus does) I can't help thinking, "but Holy Father, have mercy! Do you not know that many of us are already doing the best we can? Some of us are doing all we can to keep the family together, keep food on the table, and maybe go out to a movie once in a while.

Yes, we agree with you that excessive materialism is harmful to the spirit, but we're really not "living large." Some of us are commuting a total of four hours a day to our job, not to be rich -- not to exploit poor people, or to oppress anyone, or to ignore anyone's suffering; not to mindlessly keep up with ownership trends -- but simply to pay the utility bills, and the taxes, and the student loans, and write the checks to support the charities we believe in, and support the parish, and get the car inspected and repaired, and keep the kids in a sport or activity, like Scouting, so they can learn some worthwhile skills.

We stumble in from work, eat something we can rustle up quickly, be "family" for a while -- which is often a turbulent thing -- and then around 10PM we plop down on the couch, looking to relax a little, turn on the news -- and there you are, telling us to get up and go do something useful!

Scalia's concern would ring more truly if she were to undertake some analysis, as Pope Francis does, of the structures, specifically the economic structures, that have made the life she describes so chaotic and demanding. If our country had invested in such common-good items as better public transportation, might her commute be less long? If our country invested in its schools and safety as once it did and valued teachers and community as once it did, maybe she and her family could move back into town and spend less time commuting instead of fleeing to the suburbs for better schools and safer neighborhoods. Whether we intend to keep up with "ownership trends" or not, a home is a middle-class person's principal investment, and if you don't keep up with the trends, they will nonetheless keep up with you. She takes Pope Francis' challenge personally, which is good, but he does not simply indict our personal conduct. He indicts the systems in which we exercise that personal conduct and make us less free than we might be if our lives were simpler.

If you are in the working class, chances are keeping kids in an after-school sport is no longer something you can afford. (When did we start making kids pay for their equipment?) I know I scratched movies and regular visits to restaurants out of my budget and schedule when I went from running a small business, which paid really well, to becoming a writer, which pays less well. It does not make sense to me that I made about twice as much running a restaurant as I do writing, but that is what the market dictates, and as Pope Francis tells us, the problem with our culture is that the market dictates too much.

One of the things Americans must face is the relative loss of concern about the common good in our social and political life. This is part of the burden of Robert Putnam's new book, Our Kids. The "American Dream" was never just about me and mine getting ahead, it was about a social fabric that allowed everyone to flourish. But starting in the 1980s, the economic rules began to be rewritten. We no longer could afford to invest in our common goods because we had to shell out large tax cuts to the rich.

Once President Ronald Reagan broke the air traffic controllers' union, union-busting lost its stigma and the decline of organized labor's percentage of the workforce accelerated. Manufacturing jobs that once provided working-class families a stable income and a secure retirement were sent overseas, and we were told this was all globalization, which was as scientifically undeniable as evolution, and so we might as well just learn to get along. As pensions shrunk and then vanished, we were told we could make even more money for retirement through 401ks, turning many middle-class people into small investors, further atomizing our sense of shared responsibility and wedding many people's sense of well-being to the power of the investor class. Most of all, we became addicted to stuff. Lots of stuff. The materialism of our everyday life may have lacked the theoretical materialism of Marxism, but the capitalists succeeded where the Marxists failed. The transcendent got sidelined not by the sexual revolution, but by the consumer revolution.

That said, I want to return to Scalia's personal experiences. She may have neglected the structural causes of the anxieties that attend her life, but too often, those of us who do, like Pope Francis, decry the structural sin in our economy look only to structural solutions. We need both personal conversion and a public reckoning. The personal conversion to which we are called is not only to do more for the poor and to take steps to reduce our exploitation of the environment, it is to embrace a more simple lifestyle. This is not easy, but it is imperative. The way to resist the influence of stuff in our life is to resist the influence of stuff in our life. All the government or faith-based programs in the world cannot achieve that. We must do it for ourselves.

So if Pope Francis wants to study the situation of the middle class, I hope someone will explain that the term is no longer really viable. There is an upper middle class, which is doing pretty well. There is a working class, which is really struggling. And there is a remnant of the middle class, knowing it will soon fall into one of these two other groups and fearing that they will fall into the second group, not the first. And I hope that the Holy Father will recognize the degree to which the common good of society has been ignored in American politics these past few decades.

The politicians are only beginning to notice that fact, too. The popularity of Bernie Sanders on the presidential campaign trail stems largely from his willingness to speak the truth of justice to economic power. But it will take more than a president to fix the messes we are in, the economic, environmental and moral messes. It will take all of us. That, too, is part of the Holy Father's message. And some of us find it more encouraging than scolding because we know that the Spirit of the Lord is upon this trenchant critic of our socioeconomic system and that he sees both the structures and the person in his evaluation.