Indiana’s newly minted Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) has provoked more controversy than its authors bargained for, and more controversy than the new law deserves. But, this is the point to which our political and legal culture has brought us and it is worthwhile trying to sort through the issues – yet again – because they are not going away unless everyone, on both sides of the debate, recognizes the legitimacy of the other side’s concerns and works towards a solution, not a victory.

As regular readers know, last week I did a three-part series on these issues, without focusing on Indiana. If you have not previously read those posts, you can do so here, here and here.

Yesterday, Indiana Governor Mike Pence, who signed the new law last week, appeared on ABC’s “This Week with George Stephanopoulos.” It was an odd choice seeing as Stephanopoulos is the sharpest of all the morning anchors and the one least likely to let Pence get away with a dodge. I still can’t tell whether Pence was sincere or not in his repeated assertion that the new RFRA was not about discrimination, it was about religious freedom. He may be sincere, but only in the sense that he has come to believe his own propaganda. Pence is correct that RFRA puts limits on what the state can do. It neither requires individual citizens or corporations to do anything discriminatory nor does it prevent them from doing anything discriminatory. And, yes, nineteen other states have their own version of RFRA. That is all true. It is also besides the point.

Only in a vary narrow understanding of RFRA is it not about discrimination and, certainly, the politics of the issue, apart from the legal aspects, are very much about discrimination. The defenders of RFRA- and there is a whole slice of America’s legal profession that now focuses on religious liberty issues, allied with certain partisan groups - insist that it will protect the rights of believing Christians who do not want to get all tangled up with same sex marriage and other things that violate their conscience. They have felt that the wind was at their back, noting that the Supreme Court decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby vindicated their more expansive understanding of religious freedom and that the same court unanimously sided with their views in Hosanna Tabor v. EEOC.

On the other hand, the opponents of Indiana’s new law seem to throw out the First Amendment baby with the anti-discrimination water. They exhibit a truly disturbing lack of concern for the guarantee of religious liberty and a bizarre lack of perspective. In response to Gov. Pence correctly pointing out that President Bill Clinton signed a similar law in 1993 and that the law had passed the U.S. House unanimously and the Senate on a 97-3 vote, White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest said, “If you have to go back two decades to try to justify something you are doing today, it may raise some questions about the wisdom of what you’re doing.” Twenty years? Is that such a long period of time that a bit of consistency is to be mocked? I understand that the issue of LGBT rights has changed enormously in that period of time, but has our commitment to the First Amendment evaporated in twenty years? (Fun Fact for the day: Then-Congressman Chuck Schumer, soon to be Senate Minority Leader, introduced the federal RFRA bill in Congress.) Here is the place to note that the reason states are passing their own versions of RFRA is that the Supreme Court rules the federal RFRA did not apply to states and localities in the case City of Boerne v. Flores. (Fun Fact II: The Flores in the title of that case was former Archbishop of San Antonio Patricio Flores.)

Let’s enter our own little no spin zone. It is true that RFRA does not technically deal with discrimination issues. It is true that RFRA only puts limits on what the government can do. But, the rub is this: It is the state that passes non-discrimination laws. So, in the absence of a law banning discrimination against gays, RFRA really does seem to encourage a private company to think it can discriminate against gay people with impunity provided they cite their First Amendment religious freedom rights. But, here is the rub. The 1993 federal RFRA only restored the legal playing field to what it was before the Supreme Court’s decision in Employment Division v. Smith. That is to say, RFRA required courts to apply the Sherbert test in judging religious liberty cases. Sherbert was the 1963 case that set out the “strict scrutiny” standard for federal legislation, that is the government must demonstrate a compelling interest if it infringes on a citizen’s religious freedom, and the government must further demonstrate that the means adopted by the government to achieve that interest were the least burdensome on the citizen’s religious freedom.

Here is where the sound and fury in Indiana come in. There is no “less burdensome” way to achieve the compelling interest of non-discrimination than to ban discrimination. This was the point Mark Silk made last week in the post to which I called attention. On the other hand, in the Hobby Lobby case, the government could have found other ways to achieve its compelling interest of providing free access to contraception. It could have offered to pay for the coverage itself. It could have adopted the kind of accommodation it extended to religious non-profits. The Supreme Court did not simply state that a private corporation, in the public arena, could do whatever it wants by wrapping itself in the First Amendment and RFRA. If there was a state or federal non-discrimination law to which Hobby Lobby objected, I do not think they would win in the courts, not because contraception is less important than non-discrimination, but because there are alternatives means of attaining the government objective when it comes to distributing good or services and there is no such alternative means for ending discrimination.

One other caveat. Even if Indiana were to pass a non-discrimination law that pertains to LGBT Hoosiers, it would not apply to religious organizations in the hiring of ministers or those engaged in ministerial jobs like teaching. Here is where Hosanna Tabor comes in. That decision admits that ending discrimination is a reasonable government interest but also recognizes that trying to apply any kind of employment law to a religion’s ministers would involve way too much entanglement of the kind the First Amendment clearly wished to avoid. There is no such fear of government entanglement in suits brought against private employers in the public sphere.

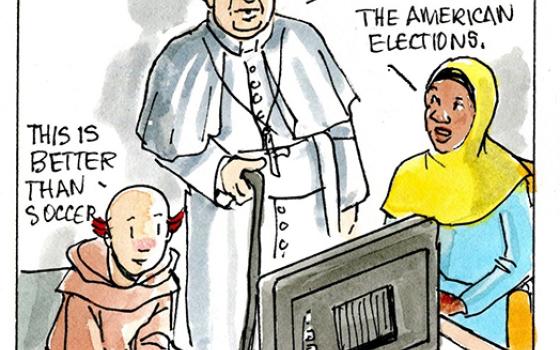

Is there a way past the talking points and misinformation coming from both sides? Sure. Groups that have been at the forefront of the fight for religious freedom, such as the U.S. Catholic Bishops, should state, clearly and unequivocally, that they support BOTH state RFRAs and state anti-discrimination laws extending to LGBT people. The Filipino bishops just did precisely that. But, the truth of the matter is that the professionals who focus on religious liberty, groups like the Becket Fund, argue that they only focus on religious liberty, not on social policy, and so it is not their place to assess non-discrimination laws except how they relate to religious liberty. That specialization is fine, but entails a certain myopia that the U.S. bishops need not adopt. Regrettably, the U.S. bishops have largely listened to groups like the Becket Fund – or hired their former litigators to work at the USCCB and so myopia has led the Church, and the nation, to this point in time. The defenders of religious liberty have so sullied the issue by linking it to bigotry (Tony Perkins was out there defending Gov. Pence on Twitter this weekend too), and aligning exclusively with the Republican Party, that millions of Americans now see our First Amendment religious freedom rights in a bad light. Fortunately, the Supreme Court is unlikely to dismiss the First Amendment so easily. But, really, is this the outcome our USCCB’s ad hoc Committee on Religious Liberty wanted? Their approach almost guaranteed this outcome. An issue that was not contentious – think of those 1993 vote totals in Congress – is now contentious because a group of people with a singular, narrow focus whipped up a frenzy among the bishops, and in almost Shakespearean ways, have brought on the thing they wanted to avoid. It has been a train wreck yet no one, not a single bishop, raised an objection when, last summer, the USCCB extended that ad hoc committee on a voice vote. No one even dared ask for a secret ballot. Unless some of the bishops re-claim their conference for the cause of sanity, I fear the cause of religious freedom will be even further tarnished.

So, what about all those religiously zealous bakers in Indiana, eager to tell a gay couple that they won’t bake a cake for them? Unless Indiana adopts a non-discrimination law that applies to public accommodations, they will be able to tell the gay couple to shop elsewhere. And, if Indiana adopts such a non-discrimination law, then they had better make the cake. But, whatever the bakers do, and whatever the legislators do, the teachers of our Church, our bishops, would do well to point out that there is nothing wrong with baking a cake for anybody for almost any occasion. Similarly, someone should tell the Little Sisters of the Poor that their conscience should not be troubled by filling out a form that exempts them from having to provide contraception coverage to their employees. Instead, we have bishops who suggest same sex marriage is a civilizational threat, which it is not, and who encourage the Little Sisters to think that signing a form is material cooperation with evil. This is what the lawyers say. The bishops should stop listening to the lawyers and begin distancing themselves from a public fight that has harmed the cause of religious liberty instead of helped it. If they don't, they have no one to blame but themselves.