Sr. Suzanne Jabro, a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, stands with a woman and child living at the Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter in Mexicali, Mexico, which Jabro supplies with essentials through her nonprofit Border Compassion. (Courtesy of Border Compassion)

Sr. Suzanne Jabro knows firsthand that migrants living at Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter in Mexicali, Mexico, face a preponderance of needs every day.

Residents at the spartan shelter 1 mile from the U.S.-Mexican border — usually housing between 80 and 150 men, women and children — lack basic essentials like food, clothes, medicine and hygiene items, Jabro said.

After all, the shelter's occupants, predominantly families, fled their homes with no provisions, she said, desperate to escape pervasive violence, poverty and climate disasters plaguing Mexico and other countries.

"They were running for their lives from violence, torture, kidnappings and embezzlement," said Jabro, 78, a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet. "The most common expression among the migrants [at the shelter] is 'I feel safe here.' "

Founded in 2021, the nonprofit invites various religious communities, churches, schools and individual volunteers to cross the border every month to provide migrants at the shelter with critical supplies, health care and legal services as they anxiously await transitioning to the next stage of their lives.

"The migrants lead us," Jabro said, touting that this cause lies "in my roots," as her own grandparents immigrated to the U.S. from Lebanon. "They tell us what they need, and we find someone out there who has the gifts to respond to the unmet need."

The shelter has long served as migrants' temporary home, she added, as they sought asylum in the United States through the legal immigration process — some waiting over a year for approval.

The entrance to the Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter in Mexicali, Mexico, where the nonprofit Border Compassion provides crucial supplies and additional services to migrants seeking asylum in America. (Courtesy of Border Compassion)

To help them survive the wait, Jabro dedicates her daily life to addressing the shelter's vast needs as the founder, chief inviter and crossover guide of her nonprofit Border Compassion.

A sponsored project of the Sisters of St. Joseph Ministerial Services, Border Compassion brought 384 volunteers to the shelter in 2024 alone, according to Jabro. Up to 60 Catholic sisters assist with the nonprofit's efforts, Jabro said, some crossing the border once a year, some several times a year.

Border Compassion's mission took on more acute importance after late January, when the Trump administration suspended asylum access at the border, including shutting down the CBP One app that had allowed asylum-seekers to schedule appointments with U.S. immigration officials.

This removed shelter residents' only option, Jabro said, adding that the new administration even canceled some of the residents' previously scheduled appointments to be granted asylum.

"They're stuck. They can't go forward, and they can't go back," said Jabro, a Los Angeles native who operates Border Compassion from her home in Palm Desert, California. "They stay where they are, because they're safe there and they've got to figure out what is the next step."

In the midst of this uncertainty, the privation at the shelter remains — and Border Compassion continues its regular border crossings to tackle it.

"We are being called forth at this time of immense change for our planet and the human family," Jabro said. "I am learning that sometimes we are the answer to someone else's prayer."

Children staying at the Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter embrace. Border Compassion often provides toys and art projects for children at the shelter. (Courtesy of Border Compassion)

Weaving a network of support

After 30 years of serving in restorative justice ministries, founding a variety of supportive programs for women's prisons, Jabro discovered a new mission when she accompanied a group of Episcopalians to the Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter in 2019.

She "was in shock" touring the aging structure that "looked like an abandoned Motel 6," she said. The 2-story, 34-room shelter offered little comfort, with three to four families per room, an outdoor kitchen and broken washing machines.

"The poverty was stark," recalled Jabro, who holds a bachelor's degree in sociology and education from Mount St. Mary's University, and a masters of divinity from Seattle University. "When you stand on any margin and look at your life from a different lens, transformation happens."

When she returned to the U.S. and discussed the shelter's circumstances with religious communities and churches, others requested to visit, too. She offered to take them every month.

"I would throw the net wide and invite others. People felt comfortable joining and not going alone," said Jabro, whose home sits an hour-and-40-minute drive from the border. "Then people started giving me money, and I said, 'I can't run all this through my personal budget.' "

She approached the St. Joseph Ministerial Services for support, she said, which granted her approval to apply for 501(c)(3) status to organize the swelling donations and volunteers.

Today, the list of Border Compassion's community and religious partners stretches long, including Episcopalians, Mormons and Jesuits, as well as high schools founded by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet.

Jabro visits the shelter as much as 15 days a month to accompany different groups of volunteers.

"It became a pure ministry," she said, adding that some groups join on border crossings, others donate items and some write checks. "When a group comes once, they go home and talk about it, and they want to come back with new people."

Advertisement

Living in uncertainty

The shelter's population remains in constant flux, said Sr. Lisa Buscher, Border Compassion's crossover engagement animator and a member of the Society of the Sacred Heart.

Roughly half of the shelter residents have journeyed from Mexican towns riddled with poverty and violence inflicted by drug cartels, she said. But depending on various crises throughout the world, occupants have also hailed from Venezuela, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Colombia, Cuba and more.

"These are all people who have the struggle to figure out, 'What is life here for me today?' " said Buscher, who accompanies volunteers across the border every month. "It's a liminal space of waiting and not knowing."

She can list hundreds of stories of traumas that shelter residents escaped, spanning torture, abductions, robberies and murdered loved ones.

The number of residents even spiked to 400 in 2023, she said, due to changes in the asylum process.

"This is a time of chaos and trauma for them," Buscher said.

Border Compassion organizes border crossings simply, with groups of volunteers walking across the border (a quicker journey than by car, where the wait can stretch for hours). They meet Jabro at a local hotel, then take taxis to the shelter.

"When we show up, it's a day of fiesta, always," said Buscher, who had friends across the border throughout her childhood in Arizona. "It brings joy in the face of suffering. It brings healing at a time of immense pain."

Visits include delivering donated essentials, as well as toys and art projects for the children. While the nonprofit never brings food across the border, Jabro said, she pays a Mexicali local to regularly purchase groceries for the shelter in town, helping boost the local economy.

Border Compassion has funded numerous shelter improvements, she added, including purchasing new washing machines, replacing smashed-in windows, paying for fumigation, installing an emergency exit, purchasing additional tables and chairs, and providing aboveground pools to help residents endure the summer's triple-digit temperatures.

The nonprofit also hired a Mexicali teacher to give English as a Second Language (or ESL) classes for adults and children at the shelter three hours a day, five days a week — the only school available for children there.

"Shelter residents who were granted asylum in the U.S. have written me back and said, 'My kid's in school, and doing really well, and it's because of the English class they took,' " Jabro said.

The nonprofit further purchases medicine for shelter residents, offers counseling services and trauma-informed self-care practices, and brings volunteer attorneys monthly to provide legal aid.

"We get to know many families very well," Jabro said.

Sr. Simone Campbell (right) and Sr. Lisa Lopez (middle), both members of the Sisters of Social Service, give a presentation about immigration law with another volunteer to residents at the Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter, one of many regular legal presentations arranged through Border Compassion. (Courtesy of Border Compassion)

Creating joyful events

Border Compassion also lightens migrants' emotional burdens.

Various groups sign up with the nonprofit to provide special events at the shelter for holidays like Dia de Muertos and Mother's Day, with each group raising $2,000 to cover food and supplies for the month.

Sr. Judy Molosky with the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet leads a group to the shelter every year from the St. Joseph Worker Program, a yearlong service opportunity for women, to entertain the children for the Mexican holiday Children's Day.

"We lavish the kids with everything from toys to face painting to lotería playing," said Molosky, 77. "Our young women relate with these kids in the shelter, from soccer playing to piñata breaking to nail painting."

Sr. Maureen O'Connor, a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet who accompanies visits to the shelter twice a year, cherishes her experience of volunteering on Mother's Day, when she played with children and assisted with art projects.

"It proved to be a profound experience as I witnessed the courage, resilience and joy of the refugees," said O'Connor, 84. "Helping a 7-year-old girl happily create, design, paint and give wings to a butterfly, while we conversed in broken Spanish and English, was particularly significant for me, as I think the child's creation symbolized her desire to be free."

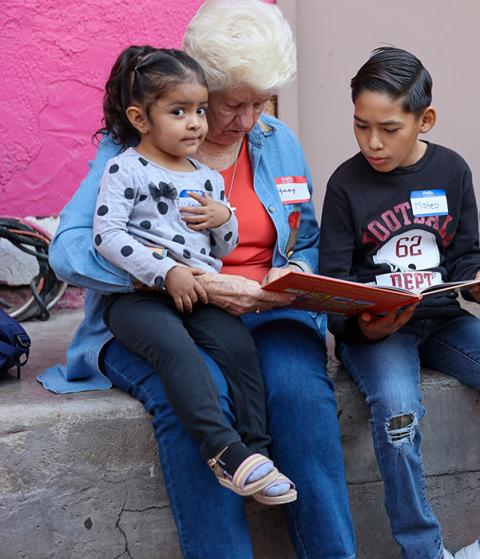

A Border Compassion volunteer reads with children residing at the Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter in Mexicali, Mexico. (Courtesy of Border Compassion)

Buscher said she impresses upon volunteers to show "kindness and compassion" from America.

"We're providing opportunities for encounters," she said. "Volunteers and those living in the shelter are both changed by the experience."

One man's journey

Border Compassion helped transform the life of a 34-year-old man from El Salvador.

The man — who preferred not to be named for his family's safety — fled his country in 2019 when a local gang began extorting him and threatened his life, the local police lacking resources to help.

When he crossed the border into Mexico, he met a woman fleeing from Honduras to escape her abusive husband. They began dating, and their ongoing hunt for work and safe lodgings led them to the Cobina Posada del Migrante Shelter when the couple — now married today — was pregnant in 2020.

Border Compassion "made a big difference" as the nonprofit provided them with food, clothing and moral support, he said.

"Every time [Jabro] comes, she's bringing people who want to give you a hug and talk to you," he said. "It's a big thing, because at least they're taking people's minds out of the shelter for just that day."

Because of his English fluency, the nonprofit tapped him to interview shelter residents to help with their asylum applications. He heard hundreds of devastating stories, he said, including a woman who had lost a hand defending her child against a machete attack.

"When you're really knowing the reason they're fleeing, it's different," he said.

He feels "so proud" of helping Border Compassion assist 473 people —127 families — in gaining asylum, he added.

After the birth of the couple's baby at a local hospital, Border Compassion helped them with every step of gaining asylum in 2021, including arranging an immigration sponsor, providing money and supervising through COVID-19 snags.

"In all my journey, Suzanne and all of the crew, they were with me and supporting me a lot," he said.

Now he works devotedly at two jobs in the U.S., with a second daughter born in America.

"Now at least I'm raising my kids without fear," he said. "This is the place that you can live your dream, if you work enough to make it real."

He still grieves, however, that his mother-in-law — whom he said he paid a ransom to free when a drug cartel kidnapped her — still remains at the shelter, along with his wife's 8-year-old daughter and 15-year-old nephew.

The new presidential administration canceled their appointments for asylum, he said.

"My wife was most affected. She was crying an entire week," he said. "They're an old lady with two little kids. They aren't criminals. Ninety-five percent of the people on the border, they're not criminals."

With America's asylum process dismantled, Jabro said, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Los Angeles Province is holding discussions to examine "the next chapter" of global migration.

They will continue collaborating with like-minded nonprofits, like those assisting torture survivors, to keep migrants safe, she noted.

"There are interlocking systems that makes it a complex issue," she said. "We're all facing it."

Sr. Anne McMullen, a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet who has helped bridge aid to immigrants since the '80s, continues advocating on behalf of Border Compassion and the shelter by lobbying local, state and federal government on immigration reform.

"I try to put a human face on the refugees in talking to legislators and to persons who are unaware of what is happening at the border, of the trauma and fear," said McMullen, 89. "My hope is that in changing hearts we can develop a just immigration policy, and no longer need Border Compassion, as we will be a welcoming community."