Tom Fox; Gloria Emerson, a correspondent for The New York Times; and Hoa Fox walk through downtown Saigon circa 1972, dressed in traditional Vietnamese farmer attire — which were often mistakenly identified as Viet Cong uniforms — while wary U.S. Military Police observe from a distance. (Courtesy of Thomas C. Fox)

The photograph known as "Napalm Girl," which depicts young Kim Phúc fleeing from napalm flames, is a powerful and defining image of the Vietnam War. It shocked the world, transcended the political backdrop of the conflict, and highlighted the profound human cost of war.

I have a personal connection with the Kim Phúc story, but first it requires some Vietnam background. In 1966, I was fresh out of Stanford University and swept up in the rampant antiwar sentiment that dominated campuses. I couldn't reconcile America's actions in Vietnam, believing the U.S. was both immoral and self-defeating. Every young man my age faced a stark choice: confront the draft, flee the country, seek a deferment, or find another way out.

I volunteered to go to Vietnam with International Voluntary Services (IVS), a private nonprofit group initially organized by the Quakers, Mennonites and Brethren peace churches — a precursor to the Peace Corps. I flew on a Pan Am 707 to the Philippines for orientation even before my senior class' official graduation ceremony.

Within days, I stepped off another Pan Am jet on a balmy June afternoon in Vietnam at Saigon's Ton San Nhut airport, the busiest airport in the world.

After several days in Saigon, I flew in a small plane to the central coastal city of Nha Trang for a month of language study and then by helicopter to Tuy Hoa, just up the coast. Tuy Hoa, the capital of Phu Yen province, was known for its heavy Viet Cong activity. The Viet Cong virtually controlled the entire area outside Tuy Hoa.

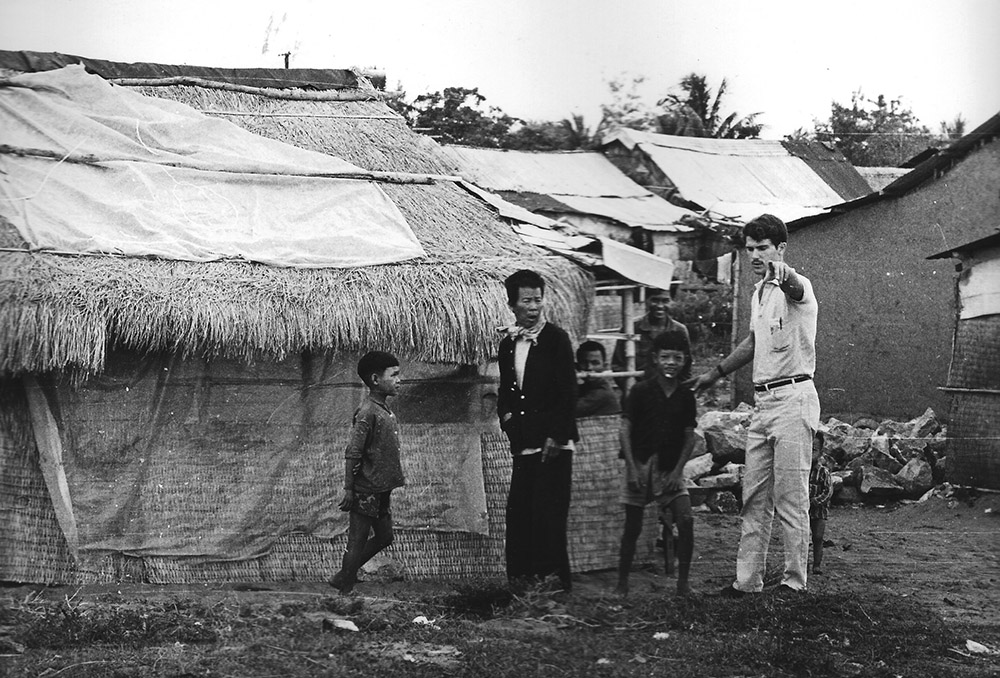

Tom Fox is photographed in 1967 with villagers at the Ninh Tinh refugee camp outside Tuy Hoa, Vietnam. (Courtesy of Thomas C. Fox)

My job was to assist several thousand refugees living in destitution on sand in the Dong Tac and Ninh Tinh refugee camps. Beyond the city limits, free-fire zones were prevalent, where the only rule was that anything moving could be targeted. Soldiers uprooted villagers from their ancestral lands and herded them onto the bare stretches of sand near the coast, lined with tin huts.

In those camps, I learned to speak simple, though heavily accented, Vietnamese. Those of us who attempted to learn the language ended up believing it was the fundamental demarcation among foreigners in Vietnam, the most critical bridge between two vastly different cultures.

I encountered people whose lives were shattered beyond recognition. I witnessed elderly men and women choosing death over displacement and saw children wandering barefoot through the scorching dust, their eyes reflecting hunger and pain.

Amid this devastation, I did what I could to help — scavenging for food, assisting families in burying their lost children, and starting minor projects like sewing classes and hat-making for young girls to prevent them from being forced into prostitution. These efforts were always fragile, sometimes destroyed when the fighting encroached.

While working for International Voluntary Services in Tuy Hoa, Vietnam, Tom Fox initiated a project where older women taught young girls to make conical straw hats, providing a small source of income. Pictured here is Fox sitting among the hat makers in 1966. (Courtesy of Thomas C. Fox)

Eighteen months after living in Tuy Hoa, I was put in charge of International Voluntary Services' refugee program, which meant keeping track of the mercilessly disrupted lives of Vietnamese throughout the nation.

My two years in Vietnam were followed by a stint at Yale, where I joined a Southeast Asia program to study the language and culture.

Between semesters, I became the foot soldier for a congressional and religious team that visited Vietnam. I guided important visitors, offering them "counter tours" to contrast the official arrangements made by U.S. agencies. When figures like Sen. Ted Kennedy visited, they received optimistic briefings from the CIA, the Defense Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

In contrast, over dinner, I would share a much darker experience, one shared by most IVSers. "It's a disaster. Everything's built on sand."

After Yale, I returned to Vietnam, where I continued to write articles for the National Catholic Reporter and began reporting for The New York Times and Time magazine.

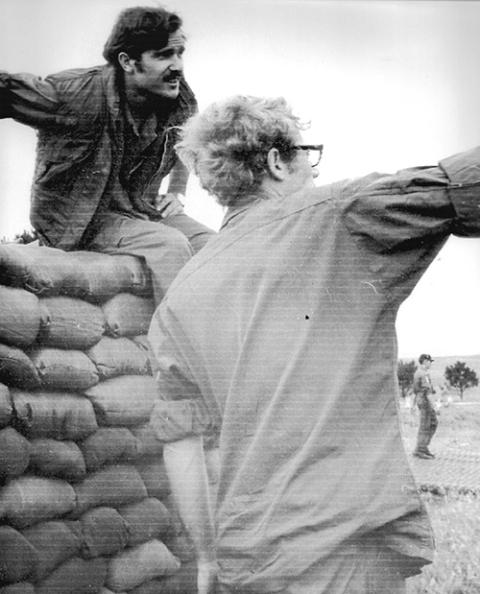

Tom Fox is seen in 1971 with Stan Cloud, the Time magazine Saigon Bureau chief, in a U.S. military compound in central Vietnam. At the time, Fox worked as a local hire for Time. (Courtesy of Thomas C. Fox)

During those years, I formed friendships with other journalists entrenched in reporting the war. One was Carl Robinson, a photo editor at the Associated Press who, like me, would have a Vietnamese spouse. We shared drinks, disillusionment and the heavy burden of our experiences.

On June 8, 1972, something happened that would darken and complicate my experience of covering the war. It was a napalm strike on Trang Bang, northwest of Saigon. That strike produced one of the war's most harrowing images: the photo of the so-called "napalm girl," Kim Phúc, running out of her village, her clothes burned off her naked body. I was in Saigon.

That photo, showing young Kim Phúc fleeing the napalm flames, appeared on the front pages of newspapers across America within hours. It became a defining image of the Vietnam War's cruelties, shocking the world, cutting through the politics of the conflict, and laying bare the human cost of war.

Interestingly, the Associated Press bureau did not know what had happened to the girl the next day. That was when Carl asked me to come to the AP office and join him and a photographer to search Saigon's hospitals for her. Carl knew I could catch up with the burn victim better because I spoke Vietnamese.

I climbed onto the back of Carl's motorbike, and we took off, searching Saigon's overcrowded, underequipped hospitals.

It might have been the first or second hospital we visited where we found the child lying in a burn ward, wrapped in bandages and inside a net. I recall vividly that the air reeked of burnt flesh.

She was awake but still in shock. I said little — I think I asked her name. Sadly, to me, she was just one more burn victim, one among countless others carried into Saigon's hospitals because of the war.

At that moment, I hadn't seen the photo and couldn't understand why someone had singled out this child — a victim among so many others being carried into and out of hospital burn units across the country.

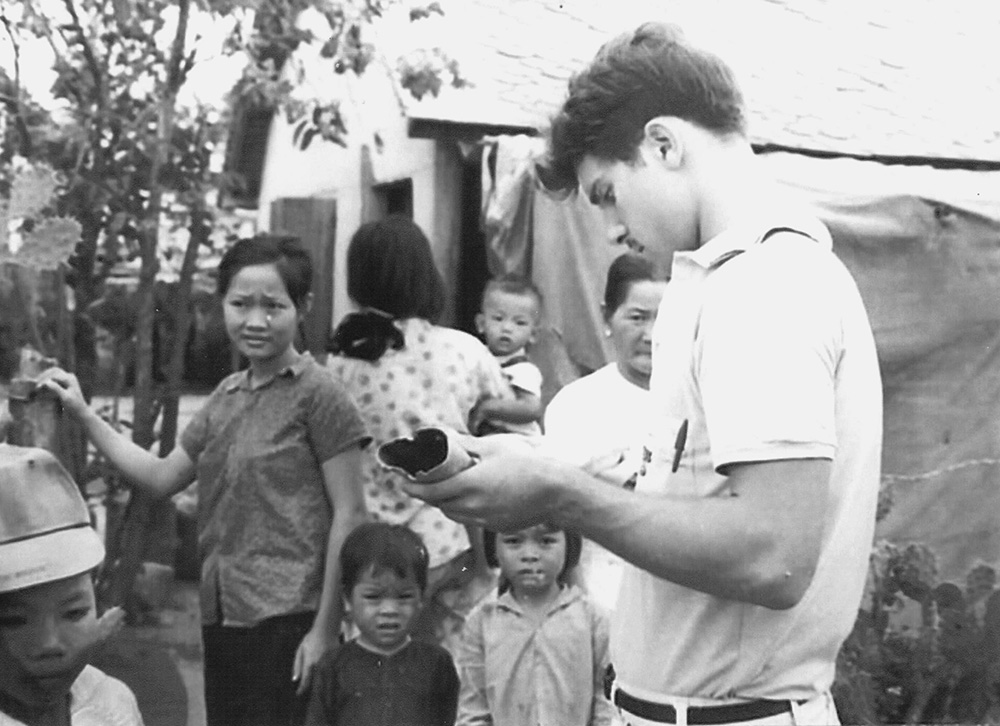

Tom Fox inspects a mortar shell that landed near his home circa 1966 in Tuy Hoa, Vietnam, while local Vietnamese residents look on. (Courtesy of Thomas C. Fox)

Carl and I stayed in touch after the war, and years later, he confessed why he had taken such a special interest in Kim Phúc. Here's how he recounted that afternoon.

Upon returning from lunch, he found the AP photo office bustling. A journalist, Jackson Iwasaki, from AP's Tokyo office, was developing and printing a film showing villagers fleeing the napalm attack. Among the images was a striking frame: the Kim Phúc film strip, on which a naked girl, her skin burned, was running toward the camera.

Amid the chaos, Carl and Jackson faced a critical decision about the photograph. The AP had an unofficial policy against publishing nudity, especially in images of children.

As they deliberated, Horst Faas, the authoritative AP photo chief in Saigon, returned from lunch and took control of the situation. Despite the visible nudity in the image, Horst decided to send the most dramatic version to New York.

I was shocked to learn what Carl told me next during a phone call from Sydney, where he had settled after the war. When it came time to caption the photo, Carl realized a freelance Vietnamese photographer had taken it.

Faas returned to the photo office after a lengthy lunch with reporter Peter Arnett. Carl checked the photographer's name as he finished typing the caption with the photo's byline. Then Faas leaned down and said firmly in his ear, "Nick Ut. Make it Nick Ut." Carl complied.

Advertisement

Why the lie? Why did Faas tell Carl to switch the credits? We will never know for sure. He died in May 2012.

Nick Ut was just 19 years old in 1972. Faas had deep bonds with Ut's family, dating back to 1965. That was when Nick's older brother, an AP photojournalist working for Faas, died tragically on assignment. Faas helped arrange and pay for the funeral.

A year later, Ut, who was just 15, applied to work at AP. A reluctant Faas hired him to work in the photo lab.

The Kim Phúc photograph would define a pivotal moment in photojournalism, and, despite not taking it, the spotlight propelled Ut forward, burdening him with unspoken deceit. Undoubtedly aware of the switch, Ut never publicly disputed the credit, living with the weight of a lie that would define his career.

Faas' choice, made in a moment of crisis, reflects the deep personal motivations and ethical gray areas that often emerge in the chaos of war.

After confiding in me, I could tell Carl was anguished about what he had done. He told me he was writing a memoir and asked if I would be his initial editor. I said yes but urged him to come clean about the story and his involvement in a historical lie. I pressed him draft after draft, pushing him toward uncomfortable honesty.

He responded that the stakes were high — Faas was dead, AP would crush him, and journalists he had known during the war would cast him aside.

Still, Carl hesitated. He feared the blowback — on himself, on Nick Ut, and on AP. But I reminded him that silence comes with its own price. Carl's coming forward, even after 50 years, was an act of liberation — for him and history.

Like me, Carl was a local hire in Saigon and did not carry the prestige or reputation of other mainstream reporters and photographers. In his memoir, which came out in 2020, Carl hedged.

The photograph transformed Ut's life, and I sometimes wondered if he grew to believe he had taken it. With the powerful picture of Kim Phúc immortalized by the media, praised by presidents and prime ministers, and even presented to Pope Francis himself, Ut fell into the acclaim and even seemed to revel in it.

Before it closed, the Newseum in Washington, D.C., displayed the photograph. The photograph hung on museum walls in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi.

Carl continued to carry the burden of what he knew and what he felt compelled to hide. We spent countless conversations reflecting on his reluctance to "stir the pot."

He had reasons to remain quiet. Challenging the Pulitzer-winning narrative meant challenging established powers — AP, its legacy, and an international media machine discouraging questions about its integrity. The pressure to conform, to let sleeping myths lie, had silenced Carl for years.

"What's wrong with one more lie?" Carl once asked me. "The war was built on lies. What difference does it make?"

But I knew that Carl's reluctance wasn't cowardice. It takes bravery — not weakness — to break decades of silence, to look at something you've long buried and decide to tell the truth. If Carl came forward, it would be a belated act of courage. And justice.

The real photographer, a freelance Vietnamese journalist who received $50 from the AP for his work that day, also lived with the deceit, believed only by a few local Vietnamese journalists and his family, who have lived with tangled hurt for decades.

Two French documentary producers heard of the story several years ago and began their investigation. First, they contacted Carl, who helped the crew locate the real Kim Phúc photographer. He lives in Los Angeles, where he brought his family after the war.

Eventually, the crew contacted me and interviewed me for several hours nearly a year ago. I have not seen the final product, but I have been told that AP and Ut continue denying the switch ever happened. When I asked Carl why he agreed to come forward after all this time, he paused briefly and said, "Well, I'm 80 years old."