(Unsplash/Greg Rakozy)

For the better part of the last two decades, I have appreciated both the scholarly and popular writings of the philosopher John Caputo, the Thomas J. Watson Professor Emeritus of Religion and Humanities at Syracuse University, and the David R. Cook Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Villanova University.

A specialist in continental philosophy, especially the areas of phenomenology and poststructuralism, Caputo's works have always had a certain religious element to them, which might be attributed in part to his deeply Catholic upbringing in the Philadelphia area in the mid-20th century. Even his earliest academic books engage figures and themes near and dear to the Catholic community: The Mystical Element in Heidegger's Thought (1978) and Heidegger and Aquinas: An Essay on Overcoming Metaphysics (1982).

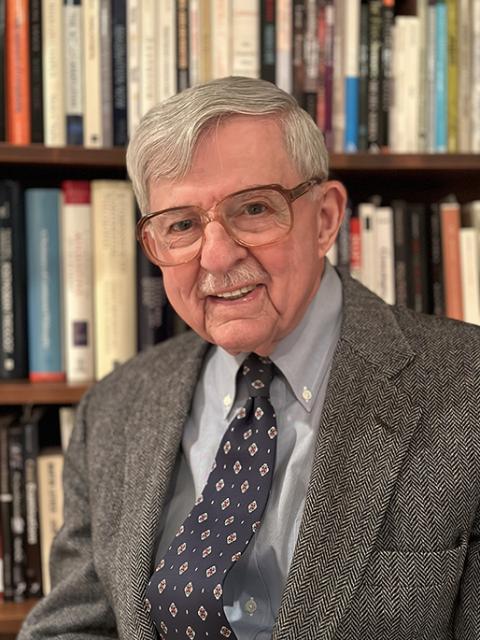

John Caputo (Courtesy of John Caputo)

In recent years, his research and writing have not only taken on a more overtly theological dimension, but have also become more autobiographical. Examples of his turn to the theological include titles like The Weakness of God: A Theology of the Event (2006), What Would Jesus Deconstruct? The Good News of Postmodernism for the Church? (2007), The Insistence of God: A Theology of Perhaps (2013), The Folly of God: A Theology of the Unconditional (2015), and Cross and Cosmos: A Theology of Difficult Glory (2019), among others.

Meanwhile, in essays and lectures, these and other recent books, and especially in the introductions to each volume of the ongoing publication of his collected papers, Caputo has been sharing more about his own life and the intersection of his upbringing in the faith, experiences in Catholic schools, his young adult years as a De La Salle Christian Brother and the development of his intellectual life.

In addition to his erudition and creativity, I admire Caputo's distinctive writing style, which is at once poetic, clever, intelligent, and often humorous. His books are not just intellectually stimulating, regardless of whether you always agree with every argument, they are also genuinely enjoyable to read, which is admittedly not something common to the professorial guild.

I recently read his latest book, What to Believe? Twelve Brief Lessons in Radical Theology, which was published in 2023. And although it was released by Columbia University Press, Caputo goes to great length to convey that it is intended for a broad, general audience and not just other scholars. Those familiar with his lifetime of work will recognize several key themes reappearing in interesting and provocative ways, inviting readers to reflect on the meaning of God, faith, church and prayer.

John Caputo's book What to Believe? Twelve Brief Lessons in Radical Theology

I found the book to be engaging and thoughtful, certain to stir the imaginations and launch meaningful conversations for those interested in having such dialogue. So, I was delighted when Caputo agreed to an interview, allowing me to ask him a few questions about his latest publication and his thinking about the church and theology today. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Horan: One of the many things I appreciate about your writing is your distinctive voice, which strikes me as simultaneously profound, playful, poetic, and accessible. How do you think about your own writing style? What informs or inspires the way you write?

Caputo: Having been raised and nurtured on the lean diet of Neo-Scholasticism that once dominated Catholic philosophy, I was shocked and fascinated by Kierkegaard's "pseudonymous" works when I first encountered them (I was still a scholastic in the De La Salle Brothers). His pseudonyms were humorists, ironists, mocking the pretensions of the philosophers in the name of the passion of concrete existence. Can you imagine Thomas Aquinas making a joke? But for Kierkegaard this was deadly serious stuff, laughing through our tears. He said humor is the incognito of the religious. I loved that. That is the key.

Later on, when I read Jacques Derrida, I found another humorist laughing through his tears, and I was converted. My first two books were written in the buttoned-down style of a tenure-track professor. But with Radical Hermeneutics (1987) everything changed. Those two had loosened my tongue (and by then I had tenure!)

While religion (or "religion without religion" as Jacques Derrida would say) has long been a major factor in your research and writing, it has been my impression that your work has taken a clear theological turn over the last 25 years. Would you agree? If so, how would you account for or understand this shift in your life and work?

I do agree, and so does Catherine Keller, who in an endorsement on the back cover of The Weakness of God (2007) said, "Caputo comes out of the closet as a theologian in this work." As usual with Catherine, she nailed it.

I started out life immersed in pre-Vatican II Catholicism, [Pope] Pius XII, Latin liturgy, the whole thing, but by the time I left the Christian Brothers, I had decided that philosophy was the only earnest way of thinking, without the trappings of authority. Especially "continental philosophy" because it had the same passion that I had found in religion, the same "restless heart" of Augustine, but without the dogmas of religion.

Then, in writing The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida (1997), I discovered someone who had put his finger on the very nerve of religion even while, as he said of himself, he "rightly passed for an atheist." That was the breakthrough, the turning point, religion without religion. There is something going on in religion, a desire beyond desire, a hope against hope, a faith that cannot be contracted into religion, into a particular set of "religious beliefs." That brought me "back" to religion, back to where I started, but differently, this time to a certain nondogmatic repetition or reinvention of religion.

So, a theologian, if you like, but with a theology I always qualify as "weak" or "radical" or, lately, as "theopoetics," describing a religion without religion that is available to anyone who wants to think about the human condition in a radical way. So there is a discontinuity with my beginnings but not a breach.

Over the years you have returned to the writings of St. Paul and other scriptural texts in your projects. I have often found that one of the impressive aspects of your work has been how seriously you take the content of the texts themselves. While others might be inclined to view your provocations negatively, I have always seen your philosophical and theological reflections as a deep and sincere engagement with what Christians claim to believe. What do you think believers and unbelievers alike can get out of engaging these texts?

However "radical" one tries to be, one is always radicalizing something. One always has a detectable pedigree, which for me is my Christian inheritance, my "tradition," which is, after all, the "Catholic principle," right? So I read the sayings and parables of Jesus about the "kingdom of God" earnestly, listening to them, not as some supernatural dictum dropped from the sky but as a poem about the human condition of which Jesus is the poet, as a head-turning insight into a unique and haunting form of life, one that scandalizes the "world" — the powers that be, the ones with the money and the power — and turns it upside down (the first are last, love your enemies, and so forth), like some kind of sacred "Alice in Wonderland."

I read Paul the same way, especially 1 Corinithians 1, which I think is the most explosive text in the New Testament, which poses a paradox for an institutional church which must proceed with a profound distrust of worldly power. This is revelation, a life-transforming vision, but in the lower case, not a capitalized Revelation, which mystifies it. In radical theology, these texts can speak for themselves. They pay their own way. They don't need a supernatural backup, or to be enforced with supernatural threats and promises. They provide an intuition into what is going on in the name of God, which we do not find in the philosophers. As Paul says, the philosophers would think this foolishness.

"St. Paul writing at his desk" by French artist Claude Vignon (Artvee)

In What to Believe? you open with a chapter titled " 'God' Does Not Exist" and talk about "theological atheism." Quickly the reader realizes that you're not denying the reality of the divine or transcendent per se, so how do you mean such a (seemingly) bold statement?

Atheism is a function of the theos [Greek for "God"] you have in mind. The Athenians thought Socrates was an atheist because he didn't think the moon was a god, and the Romans thought the Jews and Christians were atheists about the Roman gods. I am an atheist about the God of supernaturalism, the transcendent deity outside space and time, our ally in the sky who will cure cancer and get the plastic bottles out of the ocean, just so long as we pray hard enough and give up treats for Lent.

To that God — in this book I call it "𝕲𝖔𝖉," in the Latin Gothic script of the missals we used when I was a child — the "right religious and theological response" is atheism, as Paul Tillich put it. I approach the name of God — this word has a long and complex history and it has not always functioned like this, in the singular, as a proper name — as a way to name the very depths of our experience, as a limit-word, one we use when we come up against the mystery of our lives, of which the supreme being of classical theology is a reification or personification. The name of God gives form and figure to our deepest aspirations, to what we desire with a desire beyond any particular desire, to the point of excess in experience, not to a transcendence beyond experience. It is not the name of "the answer," as the bumper stickers have it, but the question.

(Unsplash/Ben Vaughn)

Later in the book you emphasize that "we are all mystics." What does it mean for someone to be a mystic?

When I was in the novitiate, they made us read the lives of saints, many of whom it turns out never existed at all, which recounted their levitations and conversations with dead people now in heaven. That is not what I mean.

Mysticism is our consciousness of unity with God, where God is the element of our lives, that in which we live and move and have our being, arising from an acute sensitivity to the unconditional value we attach to things. The mystical sense of life is not an ecstatic vision but an awareness, quiet and nonargumentative, of the mystery of being, of "the mystery we call God," as Karl Rahner wrote, of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans. This is available to anyone, and it can be set off by the most meager of things, like accidentally coming across the old beat-up hat worn by your father, now long dead, which occasions a flood of memories of your childhood, of growing up, growing old, of life and death itself. That old hat exposes us to the question raised by [Gottfried Wilhelm] Leibniz, "Why is there something rather than nothing?" Let that question really sink in! Just try! It is not a problem raised in an academic seminar but a mystery stirring in our bones, in our bowels, in our very being. Mysticism does not reduce us to silence; it gives birth to poetry. If we are not mystics in this sense, life is passing us by.

What do you mean by "radical theology"?

Radical theology is not about 𝕲𝖔𝖉, a being called God, and how we can prove that being exists. It is about what I call the event that is going on in the name of God, what is calling in that name, what is being called for, which is a form of life. The key to radical theology is to put the supernatural attitude out of action and try to ferret out the more elemental faith that is going on in religious beliefs. Beliefs are what is in our heads in virtue of an accident of birth. If you were switched at birth and raised in a completely different culture where they never heard of Jesus, you wouldn't be a Christian. You would be different, but you wouldn't be any less for that.

Advertisement

In matters of the elemental mystery of things, nobody has inside information handed down from supernatural sources. Nobody gets to go over the head of other mortals. That's a mystification, and it's dangerous. The name of God is a way to name what we truly love, but in radical theology we ask, is love the best name we have for God, or is God the best name we have for love? Preserving that undecidability is of the essence of radical theology. We should not love what we believe, we should believe what we love, what is deeply and truly worthy of our love, in which we have a faith that may or may not take the form of a religious belief and could show up in any number of different forms.

What to Believe? had me thinking about Generation Z and other people who are increasingly disaffiliating from institutional religions at record rates. What message might you have for someone who is uncomfortable with traditional religious belonging, but still is a spiritual seeker?

As I like to say, the nones are waxing, and the nuns are waning! The nones are one of my favorite audiences, exactly the kind of person I am reaching out to in this book. My question is, what can we really believe now that religion is making itself unbelievable? What we are witnessing today is that what calls itself religion is shaming God right out of existence and that this sense of what is of unconditional worth is more and more found without religion. It can be found in the arts, or the mysteries of the universe that science is uncovering, or working in an Ebola clinic in West Africa, or in everyday life. But it must be found. Without it, the result will be people with no wider vision of their lives than bigger and better shopping malls, in search of nothing grander than self-aggrandizement, people for whom nothing is sacred.

Radical theology is about what is genuinely sacred, with or without "religion," and it calls for a new species of theologians and philosophers, who are willing to repeat or reinvent the event that is going on in the name of God for a world that has been profoundly transformed and no longer believes in 𝕲𝖔𝖉, not that one at least. The Catholic principle of "tradition" means things do not have an essence, they have a history, and that it is always a question of heeding what God is doing in our times, or as I would rather put it, what is called being called for in and under the name of God in our times.