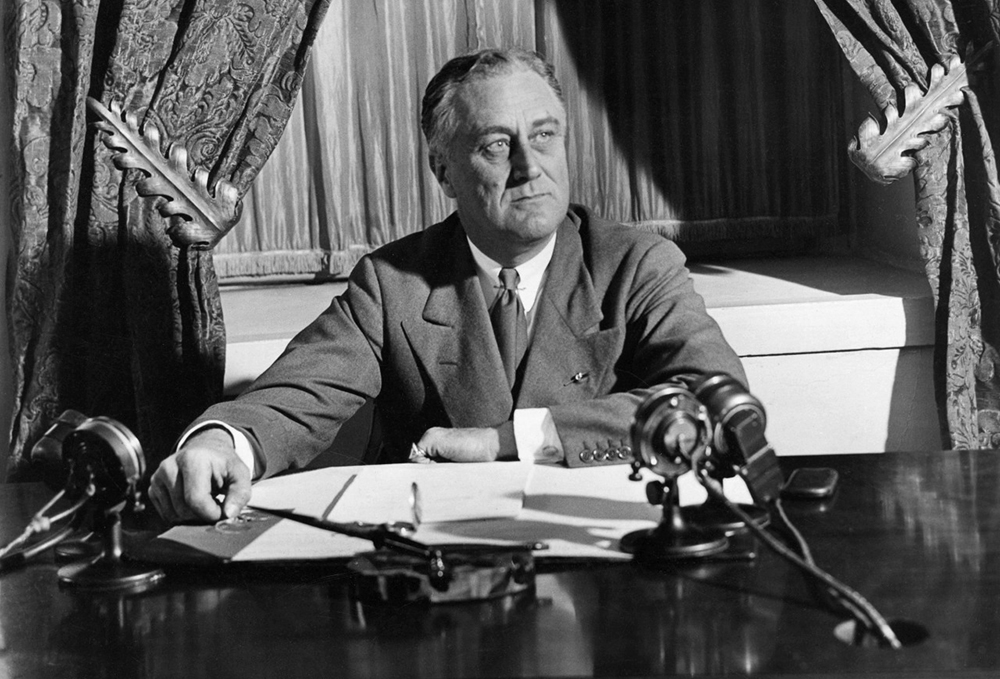

President Franklin D. Roosevelt broadcast his first fireside chat in 1933 regarding the banking crisis from the White House, Washington, D.C. (Wikimedia Commons/National Archives and Records Administration)

Is there a Catholic case for a second New Deal? That was the question posed — and answered in the affirmative — by University of Pennsylvania professor John Dilulio in a talk at the Penn Club of New York last week. Two of his respondents, E.J. Dionne of the Brookings Institution and UnHerd editor Sohrab Ahmari, agreed wholeheartedly. The third respondent, former U.S. Sen. Rick Santorum, agreed albeit with several qualifications.

Dilulio began with an elegy to the neighborhood in South Philly where he grew up. His grandmother had two statues on her mantle: St. Anthony and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He noted that the neighborhood and the church had done all they could to combat the evils of the Great Depression, but they needed more help than they could muster on their own. That is where Roosevelt came in. His New Deal created good jobs and restored a sense of respect to workers. Dilulio noted that "No one thought they needed to go to college to make a good living."

The social and political order the New Deal created is gone. Now, the more than 80 million hourly wage workers have very little in the way of security or stability in their lives, as they juggle multiple jobs and ever-higher bills to make ends meet. The pressures working-class families face are real and many families crumble under the burdens. There is an interconnectedness between good jobs and good family outcomes, Dilulio argued.

Advertisement

Catholics were a key constituency of the New Deal. They had been taught about the common good, solidarity and subsidiarity in the catechism. Catholic labor leaders could cite papal encyclicals. And they resided in ethnic neighborhoods that could easily be organized at election time. Catholics, Dilulio argued, should take the lead in making the case for a second iteration of the New Deal approach. He cited the need for new and innovative programs as well as expanding existing programs that address poverty and inequality. He called for a "radical expansion of tech education" and efforts to strengthen union organizing.

Dilulio, who was the founding director of the Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiative in the George W. Bush administration, spoke about the value of private-public partnerships. He said a summer nutrition program in Philadelphia, that extends free lunches for children when school is not in session, would collapse without the local archdiocese's work administering the program.

Dionne echoed Dilulio about the centrality of Catholic social teaching in the formation of the New Deal, citing the U.S. bishops' 1919 program for social reconstruction, which advocated many programs Roosevelt would later enact. He cited the progressive economic approaches advocated by more conservative pontiffs like St. Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI. Now, Dionne said, "Catholicism is underperforming in American political life."

Dionne noted that Catholic social teaching is essentially balanced. It promotes an equilibrium between management and workers, between federal and local governments, between economic freedom and economic security. Just so, Catholicism's "radical brand of moderation" might serve as an antidote to the political extremism that plagues the nation today.

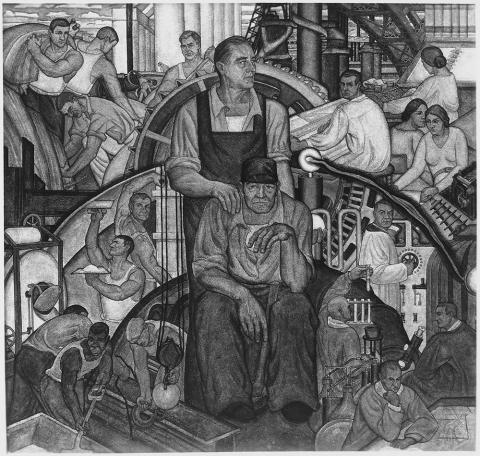

A mural painted by Conrad A. Albrizio, titled "The New Deal" and dedicated to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was placed in the auditorium of the Leonardo Da Vinci Art School in New York (Wikimedia Commons/National Archives and Records Administration)

Ahmari was the most trenchant in his criticism of today's socio-economic situation, likening it to the late 19th and early 20th century era that necessitated the New Deal. He condemned the "Wall Street asset-strippers" and made the case that raw capitalism is what unsettles everything. Consequently, modern capitalism has forfeited the right to consider itself conservative. "The market is not some mystical thing," he said. By contrast, "socially managed capitalism" of the kind that kindled the New Deal is an "essentially conservative approach," aligning it with Catholic social teaching's emphasis on social unity.

Ahmari identified his views with the mid-20th century intellectuals who embodied the New Deal principles: Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., John Kenneth Galbraith and Richard Hofstader. This warms my heart, and I hope Ahmari will find a venue to articulate the connections between these three great non-Catholic thinkers and Catholic social thought. The overlapping ideas about the right ordering of society masks the different anthropological starting points of Catholic and secular thought, and it would be good to see how they can be connected if that mask is removed. I also wish Ahmari had had time to discuss the negative effects of the financialization of the economy of which the "Wall Street asset-strippers" are a part but not the whole.

Santorum was the only politician on the panel and he said that while he agreed with the principles the others had articulated, it was less clear "how these things exist in real life." For example, he argued that the federal government does not pursue the common good as he understands it. He noted that while he was pro-union, he was opposed to public sector unions, adding that FDR also opposed public sector unions. I wish someone on the panel had pointed out that the popes who crafted Catholic social teaching were aware of public sector unions which existed in Europe, and they did not differentiate between public sector and private sector unions when they affirmed the right of workers to organize. I love FDR, but he does not enjoy magisterial status as we Catholics understand the term!

Catholicism's "radical brand of moderation" might serve as an antidote to the political extremism that plagues the nation today.

All four panelists allowed that there is an intimate connection between economic life and family life, but one of the questions that never got to the foreground was the relationship of culture to socio-economic issues, not just politics. Americans, including American Catholics, in the New Deal era, did not see themselves first and foremost as consumers. Even as late as the 1990s, a smart political operative explained to me that if voters go into the voting booth thinking of themselves as taxpayers, they lean Republican and if they think of themselves as workers, they lean Democratic. Today, a consumerist identity seems to overwhelm all else. How does Catholic social teaching address that reality?

The four panelists were convinced that there is a Catholic case for a second New Deal. I didn't need much convincing. Less clear was who, precisely, would be making that case? Catholics no longer adhere to magisterial teaching as they did in the 1930s. A bevy of lousy ideas about the relationship of religion and politics have intervened. More importantly, Catholicism at its best is a culture, of which ideas are only a part, not the whole. When Catholic ideas become dominant and are disentangled from culture, church teaching easily gets swept up in ideological battles and the culture wars. The urban, ethnic culture that gave birth to Catholicism's support for the New Deal no longer exists and Catholics have faded into the ambient culture.

Discussing the Catholic case for a second New Deal was a welcome departure from the acrimonious discussions that have accompanied the transfer of power in Washington. The panel helpfully clarified some initial issues surrounding the proposal. I hope discussion will prove seminal, and others will elaborate some of the next-level issues I have noted above. At a time when political power is being deployed in such raw and unjustifiable ways, thinking about a better kind of politics may seem a little disconnected from reality. But we can perform triage and think ahead at the same time. Both are necessary.