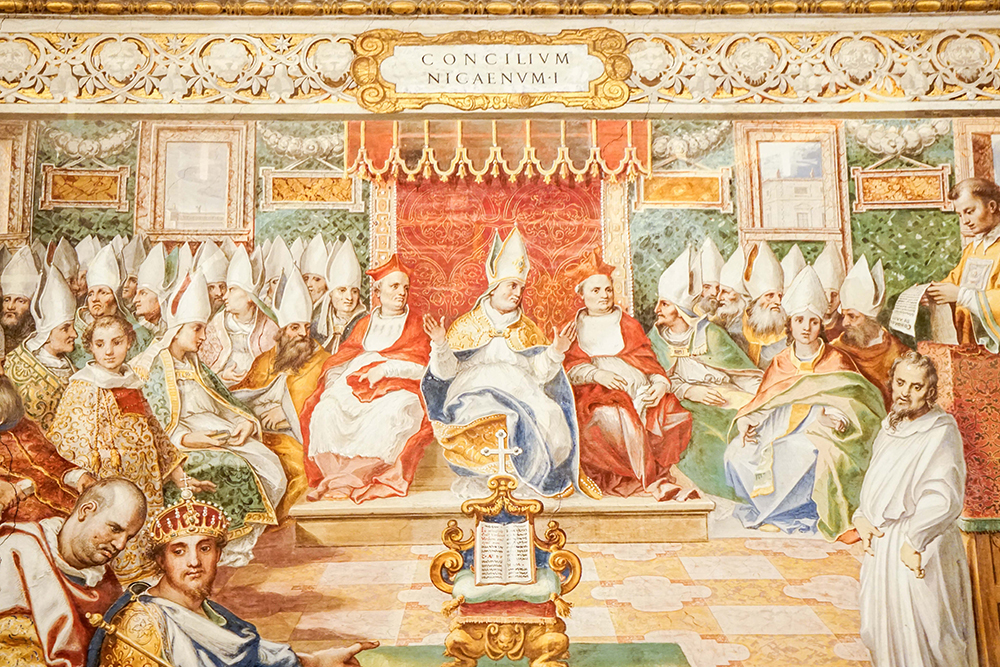

A wall fresco depicting the First Council of Nicaea can be seen in this photo taken in the Sistine hall of the Vatican Library July 19, 2023. The council was held in 325 and its 1700th anniversary will coincide with the Holy Year 2025. (CNS/Carol Glatz)

History curates.

In the first half of the 18th century, there were hundreds of organists and choirmasters in Germany, dozens of whom composed music for Sunday liturgies. But the only one whose music we listen to today is Johann Sebastian Bach. The beauty of his music has survived through the centuries.

Real estate listings often describe a newly built house as "colonial" meaning that the style mimics what a certain kind of colonial America home looked like: Center door flanked by two windows on either side, a second story immediately above, all symmetrical. (Incidentally, only fairly wealthy people had houses like that in the colonial period.) The style is still enormously popular because it is functional and aesthetically pleasing.

There are countless other examples one could cite of history winnowing out the work and ideas of lesser artists and peoples, but preserving the best.

For Americans, we think of something from the 18th century as old. Next year, in 2026, we will celebrate the 250th anniversary of American independence from Great Britain. But then one goes to Rome and visits the Basilica di San Clemente, admiring the medieval mosaics and schola cantorum, before climbing down to the remains of the fourth century church below. The previous church was filled in and forgotten until excavations unearthed them in the 19th century.

The interior of the Basilica di San Clemente in Rome (Wikimedia Commons/Ninfamania)

This year marks the 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea. Unlike the long-forgotten excavated remains of the earlier church at San Clemente, every Sunday we recite the creedal formula the bishops devised and approved at Nicaea. The words have great staying power, still affecting our existence in such a palpable way. "Let us stand and recite our Creed" or "the Creed," the celebrant says, not "their Creed." Adherence to the Nicene Creed remains a necessary marker of orthodoxy.

We even have a common phrase that has come down to us from Nicaea: When we say "there is not an iota's worth of difference," we are recalling, knowingly or not, the Christological debate at that council. The debate hinged on the difference between the Greek words homoousios and homoiousios, consubstantial or only very much alike. The Arians who refused to believe Jesus Christ was fully God were more numerous at the council and throughout the world. Yet they lost the debate, and while it took some time for orthodoxy to win the day throughout the universal church, it did so.

The Creed's continued vitality in the life of the Christian Church is owed not only to its antiquity. We still say the words given to us by the fourth century council fathers because we believe those words are true. The council held that Christ is "God from God, light from light, true God from true God." And we believe that. Every time we pray to Jesus, we know in faith that we are praying to God, not to a mere mortal. Jesus is not only a great teacher or wise counselor. We believe Jesus is truly God.

We believe in the Holy Trinity as articulated by the council of Nicaea. We believe Christ rose from the dead. We believe the church is "one, holy, catholic and apostolic," even if its members and leaders are sometimes divided, worldly, sectarian and a counterwitness to the Resurrection. All this is in the Creed.

Advertisement

It is interesting to note that there is something you won't find in the Nicene Creed: There is no ethical statement. Indeed, the entire earthly life of Jesus is passed over. We go directly from "incarnate of the Virgin Mary" to "crucified under Pontius Pilate." There is no reference to any parable, no Sermon on the Mount. In our time and place, when the reduction of religion to ethics is the norm, the Creed is a startling reminder that our contemporary norm is wrong.

To be sure, there are creedal statements with profound ethical implications. We state of Jesus Christ that "through him all things were made." We have not always treated the earth or each other as if all was made "through him," but the Creed calls us precisely to that recognition. Everything is a gift, given to us in Jesus Christ. This is the source of our Catholic humanism, of our defense of human life from the womb to the tomb, of our commitment to protect the environment. Whatever challenges or sufferings our commitments entail, we cannot abandon them without betraying the very ground of our being.

Some great works of music have been inspired by the words of Creed or, better to say, by the realities to which those words point. Mozart's "Et Incarnatus est" from the Mass in C minor, K 427, Schubert's version of the same text in his Mass in E flat, and Bach's "Credo in Unum Deum" from the B minor Mass are still sung with regularity because of the beauty with which they capture the dogmatic beliefs that animate our faith.

In his book The Spirit of Early Christian Thought, Robert Louis Wilken writes of the Nicene era:

Christian thinking is anchored in the church's life, sustained by such devotional practices as the daily recitation of the psalms, and nurtured by the liturgy in particular, the regular celebration of the Eucharist. Theory was not an end in itself, and concepts and abstractions were always put at the service of a deeper immersion in the res, the thing itself, the mystery of Christ and the practice of the Christian life.

In the post-Vatican II era, most preachers stick closely to the biblical texts of the day. But they need to take the time to explicate the dogmatic beliefs of our faith as well. It isn't impossible: The great fathers of the early church were steeped in Biblical imagery and teaching.

The Nicene Creed contains the heart of our dogmatic beliefs as Catholic Christians. Much has changed about the life of the church in the past 1,700 years, but the creed the council fathers fashioned is still recited by us, it still shapes and defines us as a church. It is an astounding thing.