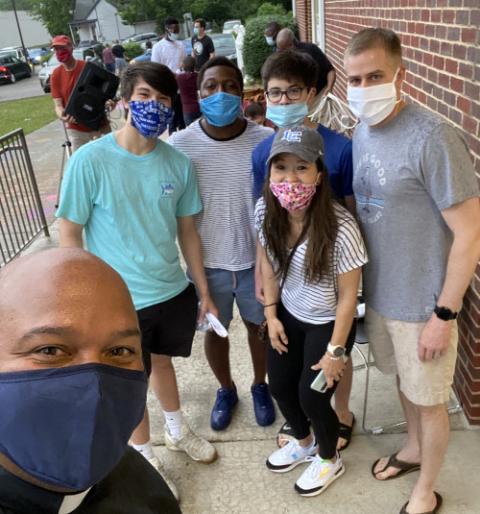

Fr. Norman Fischer, pastor of St. Peter Claver, is pictured with parish youth at a racial reconciliation service June 4. (Provided photo)

Fr. Norman Fischer, pastor of St. Peter Claver, is pictured with parish youth at a racial reconciliation service June 4. (Provided photo)

I turned 67 on April 28 and received a new kidney last November.

George Floyd, 46, of Minneapolis was not so lucky. He died on May 25, Memorial Day.

He left his home for an errand, or perhaps a beer run — it really does not matter now. Four Minneapolis police officers changed his plans.

Detained and arrested on an alleged forgery charge, Floyd ended up with officer Derek Chauvin's knee in his neck for eight minutes, 46 seconds, until he died.

Protests, starting on May 26, continue and on June 1 here, the local protest came within two blocks of my apartment building, the participants clearly visible.

Catholic and interfaith clergy here report that they, and their respective flocks, are hurting.

Fr. Norman Fischer has been pastor of St. Peter Claver Catholic Church — and chaplain at Lexington Catholic High School — for 15 years. St. Peter Claver is central Kentucky's oldest black Catholic parish. It originated in 1887.

A major supporter of the parish was St. Katharine Drexel, who helped establish its school, the first for African American children in Kentucky.

"This (police brutality and George Floyd's killing) is something that we have to fight with the fire of the Holy Spirit, because as our tenets of social justice proclaim, when one person suffers, we all suffer," said Fischer.

He stressed that any protest "must be daily and not just focused on this one instance of police brutality. We have had three separate tragedies in three months — [Ahmaud] Arbery in Georgia, Breonna Taylor in Louisville and now George Floyd," said Fischer.

As to how Floyd's death has affected his parish, Fischer said, "everyone is in pain; there is a lot of angst."

Deacon James Weathers, director of parish life at St. Peter Claver, oversees the spiritual growth of the parish's more than 250 families.

He expressed approval of the protesters who are taking to Lexington's downtown streets but said, "I am not happy with some of the things going on around them."

Deacon James Weathers (Provided photo)

Weathers noted that "some of our parishioners are afraid the agitators in these crowds — those who might say 'I don't like Catholics' — might pass by St. Peter Claver, break in and wreck something."

Weathers was also less than complimentary about the state of race in our land today.

"I have grown sons and grandsons whom I worry about all the time — about their getting stopped by the police or watched when shopping while black," said Weathers. "In our community, these types of things happen all the time."

The Rev. James Thurman, associate minister at Shiloh Baptist Church here, is the former president of the NAACP's Lexington chapter.

"People are protesting over more than just George Floyd's death, because this has been going on for a long time. It's a disease — and the name of it is racism," said Thurman.

Speaking about the Lexington Police Department — whose officers at the May 30-31 weekend protest eventually took a knee of which some people present said they took grudgingly — Thurman summed up its past leadership.

"Our first black police chief — Anthony Bailey — started some reforms during his tenure in the 1970s, and a later chief, Ronnie Bastin, continued them, but when he retired in 2017 to run for mayor (unsuccessfully), his successor started changing them backward and we experienced a downturn," Thurman said.

Lexington's current police chief is Lawrence Weathers, who is coping with a growing drug problem and a homicide rate that in 2019 totaled 29 murders, breaking a record.

In the midst of all this, after three years of testing with the University of Kentucky Transplant Center, I applied to the University of Cincinnati transplant program in April 2019. Six months later, my name went before their selection panel.

I was approved for the waitlist on Oct. 14 and listed the next day. Eighteen days later, a new kidney became available and was mine.

As I slept Nov. 1, following three hours of dialysis that afternoon, someone else's life ended — and my second chance at one began.

Seven months later, my immune system has been reborn, the anti-rejection medications sharply reduced, and my clinic visits are now just monthly.

George Floyd, however, age 46, is still dead.

Advertisement

Now, as COVID-19 rages unchecked, I must add personal safety to my medical concerns, because my new organ must not be damaged — either by rioters, white supremacist vigilantes or an overzealous police response.

Three months before COVID-19 arrived here, I was wearing PPE on a daily basis and confined to my home for 90 days.

Many people have told me, "God is saving you for something," and we all readily agree that just waiting those 18 days was truly a miracle.

On May 29, authorities in Minneapolis charged Chauvin with third-degree murder and manslaughter. Those charges were upgraded on June 3 to second-degree murder. I have reflected often since George Floyd's death how fortunate I am in another way.

Several times during my lifetime, I could have died at the hands of the police. In 1983, on the Fourth of July, I was working in Columbus, Ohio, for the old Columbus Citizen-Journal newspaper.

I drove to a nearby automotive parts store at a mini-mall in the white suburb of Minerva Park. While I was there, the jewelry store next door was robbed, and I collided with the robber as we both left these two businesses at the same time. I was knocked down by the fleeing thief, who was armed with a butcher knife.

When responding officers from the Columbus Police Department arrived, I was promptly detained and handcuffed. Even after the store's owner cleared me immediately at the scene, they took me to a neighboring precinct lock-up.

The reason? An outstanding $40 traffic ticket, which one officer asked if I could pay then and there. I could, but another officer overruled him, preferring that I spend a night in jail instead.

George Floyd never went to jail Memorial Day.

While attending the University of Dayton in the late 1970s, I was followed by a police cruiser I had just passed in downtown Dayton on East Third Street.

The officers hit their lights, pulled me over, and drew their guns on both sides of my car. Another police cruiser drove slowly by, allowing an older white man inside to look at me, shake his head, and — I found out moments later — dismiss me as the person who had just robbed him.

Two black officers let me go with the thinnest of explanations, much hostility and no apology.

The Rev. James Thurman (Provided photo)

After the Minerva Park incident, I sought an apology from the black commander of the Columbus precinct where I was held overnight.

"I am sorry for your night in jail and missing the July Fourth fireworks, Mr. Glover, but our department believes that it is better to lock up a dozen innocent men rather than let one guilty person go free," I remember he told me.

In Lexington today, things are both tense and fearful, COVID-19 included.

Every day, however, I proudly wear the "Donate Life," "Give Thanks," "Give Life" emblems I downloaded, laminated and now carry on my bookbag and laptop cover. Just my way of saying thanks to God for a miracle.

As I retire each evening, I will remember them all. And I will ask God to keep me safe in a very tense, fearful city. I will ask him again to bless my donor's family, to protect this blessing that their loved one wanted someone to have.

A miracle that won't help George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and many other African Americans.

[Robert Alan Glover writes for Catholic News Service, The Tennessee Register in the Diocese of Nashville, and FAITH magazine in the Diocese of Memphis. He lives in Lexington.]